When the rainbow arching high

Looks from the zenith round the sky

Lit with exquisite tints seven

Caught from angels' wings in heaven,

Double, and higher than his World

The wrought rim of heaven's font,

Then may I upwards gaze and see the deepening intensity

Of the air-blended diadem . . .

Ending in sweet uncertainty 'twixt real hue and phantasy.

— Gerard Manley Hopkins, 'II Mystico', ll. 107-15, 121-2

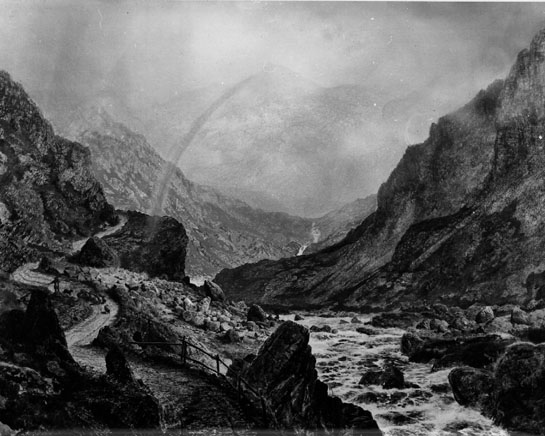

he Leeds City Art Gallery contains a landscape by Atkinson Grimshaw that is especially intriguing to anyone interested in iconology. In particular, Grimshaw's oil painting reveals much [156/157 about the difficulties nineteenth century artists and writers faced when they attempted to transform facts of nature into paradigmatic images, tropes, or situations. This representation of a mountain stream with rainbow has little to differentiate it visually from other carefully observed nineteenth-century representations of nature in its rougher aspect. Utilizing the sharp declivities of rock-walled valleys on both sides of his canvas, the painter carries our eye into a picture space that has a remarkably conservative — that is, remarkably Claudean or Wilsonian — organization for a work of the latter half of the nineteenth century. Hillsides replace the Claudean (or Turnerian) tree, but the same motifs divide the picture into foreground, middle distance, and distance, while the traditional winding stream serves to unite these spatial zones. Within this rocky world a single shepherd and his small flock provide the only life and the only sense of scale; and this figure's back, perhaps significantly, is turned away from the beautiful rainbow that reaches down from the sky to touch the earth not far from where he stands. This rainbow serves as an important compositional element, creating the second half of an ellipse, the first part of which is formed by the steep hillside on the right.

he Leeds City Art Gallery contains a landscape by Atkinson Grimshaw that is especially intriguing to anyone interested in iconology. In particular, Grimshaw's oil painting reveals much [156/157 about the difficulties nineteenth century artists and writers faced when they attempted to transform facts of nature into paradigmatic images, tropes, or situations. This representation of a mountain stream with rainbow has little to differentiate it visually from other carefully observed nineteenth-century representations of nature in its rougher aspect. Utilizing the sharp declivities of rock-walled valleys on both sides of his canvas, the painter carries our eye into a picture space that has a remarkably conservative — that is, remarkably Claudean or Wilsonian — organization for a work of the latter half of the nineteenth century. Hillsides replace the Claudean (or Turnerian) tree, but the same motifs divide the picture into foreground, middle distance, and distance, while the traditional winding stream serves to unite these spatial zones. Within this rocky world a single shepherd and his small flock provide the only life and the only sense of scale; and this figure's back, perhaps significantly, is turned away from the beautiful rainbow that reaches down from the sky to touch the earth not far from where he stands. This rainbow serves as an important compositional element, creating the second half of an ellipse, the first part of which is formed by the steep hillside on the right.

The Seal of the Covenant by Atkinson Grimshaw. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Grimshaw's painting differs from most nineteenth-century portrayals of the rainbow, which most often depict it above either a flat, open plain or a woodland scene, but like them it uses one of nature's more lovely optical phenomena to provide a striking visual motif. It does not, however, seem to have anything that distinguishes it iconsographically from other pictures of the rainbow, such as Constable's Hampstead Heath with a Rainbow (1836, Tate Gallery) or Turner's Buttermere Lake (1798, Tate Gallery). One is thus somewhat jarred to discover that Grimshaw has chosen to call his work The Seal of the Covenant, thereby claiming a religious significance for the scene before us which it does not seem to warrant. In other words, the verbal context this title provides for the visual image does not match our experience of it.

The Seal of the Covenant is not unique among nineteenth-century works of art and literature in the problematic uses it makes of this traditional landscape motif. J. T. Linnell's The Rainbow (1863), now in the Forbes Magazine Collection, similarly directs the spectator to perceive an ordinary English landscape existing within the context of biblical events. Less unusual in its setting than The Seal of the Covenant, Linnell's now sadly deteriorated painting includes its rainbow as part of a pastoral scene framed by a woodland setting; [157/158] and here it seems to betray the obvious influence of the famous Rubens Landscape with a Rainbow (1635-8, Wallace Collection, London) and its many heirs, which include Paul Sandby's The Rainbow (after 1802, Nottingham).

The Rainbow by J. T. Linnell. [Click on thumnbail for larger image.]

Our problem with this picture comes not from its title but from the scriptural text that Linnell placed on his frame as an epigraph: 'And it shall come to pass, when I bring a cloud over the earth, that the bow shall be seen in the clouds' (Genesis 9: 14). Although one does not react so strongly to this painting as to Grimshaw's, perhaps, the suggestion that this English scene embodies God 's covenant with man is nonetheless disturbing because again one encounters an obvious separation of word and image. One doubts either these painters' control over their materials or their sincerity, so that one is driven to inquire how essential are that title and that text from Genesis to the pictures themselves. In other words, these rainbow landscapes lead us to the question, can a painting of nature exist independently of the verbal statements about that nature which the artist himself appends to it? Or, to rephrase that problem in terms more acceptable to the twentieth century, must a painting of nature exist independently of verbal statements about it?

That these paintings by Grimshaw and Linnell lead directly to such crucial questions tells us much about the situation of landscape painting in the nineteenth century. To claim religious significance of the rainbow is to make definite assertions about man, God, and nature. Furthermore, to make such a claim in work of visual art is to make an assertion about both that art and the audience for whom it is intended. Our reactions to these rainbow landscapes make clear that we do not grant all these claims. Let us look at some of these claims to see why they make these rainbow landscapes so problematic .

There was certainly ample precedent for thus endowing the rainbow with sacred meaning, and therefore the difficulties we encounter with these paintings by Linnell and Grimshaw do not arise in any eccentric personal symbolism, such as one comes upon in the works of Blake and Friedrich. A long tradition had made the rainbow a commonplace symbol of peace, hope, and grace not only in scriptural exegetics but also in pictorial and literary iconography as well. The source of this iconographical tradition is Genesis, which explicitly makes this optical phenomenon a divinely instituted covenant-sign: [158/159]

There was certainly ample precedent for thus endowing the rainbow with sacred meaning, and therefore the difficulties we encounter with these paintings by Linnell and Grimshaw do not arise in any eccentric personal symbolism, such as one comes upon in the works of Blake and Friedrich. A long tradition had made the rainbow a commonplace symbol of peace, hope, and grace not only in scriptural exegetics but also in pictorial and literary iconography as well. The source of this iconographical tradition is Genesis, which explicitly makes this optical phenomenon a divinely instituted covenant-sign: [158/159]

And God said, This is the token of the covenant which I make between me and you and every living creature that is with you, for perpetual generations:

I do set my bow in the cloud, and it shall be for a token of the covenant between me and the earth.

And it shall come to pass, when I bring a cloud over the earth, that the bow shall be seen in the cloud:

And I will remember my covenant, which is between me and you and every living creature of an flesh; and the waters shall no more become a flood to destroy an flesh.

And the bow shall be in the cloud; and I will look upon it, that I may remember the everlasting covenant between God and every living creature that is upon the earth.

And God said unto Noah, This is the token of the covenant, which I have established between me and an flesh that is upon the earth. [Genesis 9: 12 17]

According to the Bible, then, the Lord Himself specifically made the natural phenomenon of the rainbow to function as a sign. In St Augustine's De doctrina christiana, his treatise on the correct manner for reading scripture, he explained that God made two books — the Bible and the book of the world. But only in the Bible do natural objects have symbolical or allegorical significance, for it is only within the context of a divinely inspired narrative or other discourse that natural facts can possess a fuller, or (as St. Augustine would put it) spiritual, meaning. However, as this passage from Genesis makes quite clear, the rainbow possesses a unique status: in its natural context, as an event that occurs after any rainstorm when the light conditions are adequate, it functions linguistically and symbolically as a divinely instituted sign. The rainbow, in other words, is a prime example of a natural object or event interpreted as part of an allegorical, sacramental universe. One problem that artists and writers in the nineteenth century had to face, then, was that although many men no longer accepted such a vision of reality, the Bible made it abundantly clear that the rainbow should be understood in this manner.

As Patrick Fairbairn, a popular interpreter of the Bible, explained to his audience in The Typology of Scripture, "The fitness of the rainbow . . . to serve as a sign of the covenant made with Noah, is all that could be desired, because there is an 'exact correspondence between the [159/160] natural phenomenon it represents, and the moral use to which it is applied." Such a divine promise means, not that God win never again visit His judgment upon guilty men, but that He will never again do so to the extent that He win destroy the world. In the moral as in the natural sphere, says Fairbairn, storms will occur, but no second Deluge win follow since God's mercy will always thus "rejoice against judgment." The most important significance of the rainbow is as an emblem, a promise, of grace:

How appropriate an emblem of that grace which should always show itself ready to return after wrath! Grace still sparing and preserving, even when storms of judgment have been bursting forth upon the guilty! And as the rainbow throws its radiant arch over the expanse between heaven and earth, uniting the two together again as with a wreath of beauty, after they have been engaged in an elemental war, what a fitting image does it present to the thoughtful eye of the essential harmony that still undoubtedly is its symbolic import, as the sign peculiarly connected with the covenant of Noah; it holds out, by means of its very form and nature, as assurance of God's mercy, as engaged to keep perpetually in check the floods of deserved wrath, and continue to the world the manifestation of His grace and goodness. ['The New World and its Inheritors'].

For the Christian the most important manifestation of God's grace and goodness was, of course, Christ; and long exegetical tradition held that the rainbow served not only to record God's covenant with Noah but also as a type of the second, or new, covenant, brought by Christ. As Thomas Scott's popular Bible commentary pointed out, it is "the new covenant, with its blessings and securities, which in an these events was prefigured."

The audience in Victorian England, where this tradition seems to have retained vitality longer than anywhere else, learned this interpretation of the rainbow not only from preachers and scriptural expositors but also from a revered tradition of devotional poetry. The London Religious Tract Society included several such traditional readings of the heavenly arch in its English Sacred Poetry of the Olden Time (1864). Henry Vaughan's "The Rainbow," for example, relates how gratefully the poet catches sight of this

Bright pledge of peace and sunshine, the sure tie

Of the Lord's hand, the object of His eye!

When I behold thee, though my light be dim,

Distant, and low, I can in thine see

Him Who looks upon thee from His glorious throne,

And minds the covenant betwixt an and One.

Vaughan's poem is of particular interest to us because he thus reacts to the rainbow as a divinely instituted covenant-sign when coming upon the rainbow in a natural, not a biblical, setting. He does not, in other words, merely interpret the scene of the rainbow's first appearance in Genesis but rather interprets the scene with the rainbow in which he, Henry Vaughan, a man of the seventeenth century, finds himself; and for this reason his poem is a direct verbal analogue to the paintings of Linnell and Grimshaw. In contrast, Paradise Lost, which many nineteenth-century Evangelicals read as a doctrinal tract, explains the significance of the Bible scene. When Adam asks Michael the meaning of the "color'd streaks in Heaven," his angelic teacher instructs him that they have been placed there to remind the sons of Adam that

Such grace shall one just Man find in his sight,

That he relents, not to blot out mankind,

And makes a covenant never to destroy

The earth again by flood, nor rain to drown the world

With man therein or beast; but where he brings

Over the earth a cloud, with therein set

His triple-color'd bow, whereon to look

And can to mind his Covenant. [bk XI, 11. 890-71

Both Noah and the rainbow itself were types of the Christian dispensation, and the covenants to which both Milton and Vaughan refer are the new as wen as the old, for the one just man is that second, greater man, Christ. George Gascoigne's "Good Morlow," which also appeared in the Tract Society volume, explicitly relates the grace signified by the rainbow to his Saviour:

The rainbow bending in the sky,

Bedecked with sundry hues,

Is like the seat of God on high, [161/162]

And seems to ten this new:

That as thereby He promised

To drown the world no more,

So, by the blood which Christ hath shed,

He will our health restore.

The Rev. L. B. White, editor of Sacred Poetry in the Olden Time, assists our study of this image by referring his reader to Thomas Campbell's "To the Rainbow," which rejoices that God never "lets the type grow pale with age/ That first spoke peace to man." Like Milton, Vaughan, and Gascoigne, this nineteenth-century poet accepts a sacred meaning of this optical occurrence in the heavens. One cannot tell whether by "type" Campbell means that the rainbow prefigures Christ or is merely a symbol of His mercies, but his interpretation of the rainbow in traditional Christian terms is evident.

Although such readings of the rainbow are not common among Victorian English poets, one finds a few examples, and one finds them in just the poets one might expect — Newman, Keble, and Hopkins. For example in his early lines on "My Lady Nature and Her Daughters," Newman appears to allude to the notion of the rainbow as a sign of divine grace, and he far more explicitly develops this notion in his sonnet "Hope." Explaining that ever since "the stern baptism" of the Flood, we are no longer the children of "a guilty sire," he admits that the Deluge did not wash us clean enough to return to Eden.

But thoughts were stirr'd of Him who was to come

Whose rainbow hues so streak'd the o'ershadowing gloom,

That faith could e'en that desolate scene admire.

Now that Christ has "come and gone" from earth, we await, says Newman, the "second substance of the deluge type,/ When our slight ark shall cross a molten surge" at the Last Judgment, and after judgment we shall enter "Eden's long-lost gate." Here the rainbow is clearly Christ Himself, as it is in John Keble's "Quinquagesima Sunday," which asserts that the rainbow, like Christ Himself, exemplifies God's merciful accommodation to man:

The Son of Man in radiance beam'd

Too bright for us to scan, [162/163]

But we may face the rays that stream'd

From the mild Son of Man.

As he further explains, "God by his bow" writes in the sky that "every grace is love." John Ruskin draws upon much the same exegetical tradition when he explains in the last volume of Modern Painters that "the bow, or colour of the cloud, signifies always mercy, the sparing of life." The sunlight, symbol of God's righteousness, is, like that righteousness itself; too intense for man to contemplate directly, and so God mercifully "divided, and softened [this sunlight] into colour . . . Thus divided. the sunlight is the type of the wisdom of God, becoming sanctification and redemption." Clearly, at this point in his life, Ruskin, like Newman and Keble, conceived the world in a manner more characteristic of the Middle Ages than of the reign of Victoria.1 All three — Evangelical, High Churchman, and Roman Catholic — accept that the glorious optical phenomenon of the rainbow is a divine messenger, a perpetually reappearing sign of the old and new covenants. An three, in other words, were able to read natural phenomena as if such phenomena contained a language of divinely instituted symbols.

Gerard Manley Hopkins was another major Victorian author who shared this attitude towards nature. As one can see from the closing lines of "The Caged Skylark," Hopkins was able to make traditional interpretations of the rainbow part of his characteristically complex theological wit. Likening man's spirit to a caged bird, Hopkins concludes,

Man's spirit will be flesh-bound when found at best,

But uncumbered: meadow-down is not distressed

For a rainbow footing it nor he for his bones risen.

The poet's play upon "distressed" well prepares us to recognize not only the rainbow's lack of earthly weight but also the way God frees man from the "stress" of his terrestrial, fallen existence. The rainbow in this poem, unlike the others at which we have looked, appears within an analogy, but it nonetheless seems clear that Hopkins employs it for an its traditional significances — and that he accepts them.

Noah's Sacrifice by Daniel Maclise. [Click on the thumbnail for a larger image.]

Since the traditional religious symbolism of the rainbow plays such an effective part in these various poems, one wonders why it [163/164] should appear so problematic in the paintings by Linnell and Grimshaw. One might assume that this is a simple matter of symbolism functioning differently in painting and poetry, but we do not in fact encounter the same difficulties when we view nineteenth-century representations of Noah's sacrifice such as that by Daniel Maclise (1847, Leeds City Art Gallery) for the popular Bible illustrations by Gustav Jager. Such portrayals of the scriptural narrative of course had a long pictorial as well as literary tradition attached to them. For instance, Cesare Ripa's iconologia (1603) includes such a scene of Noah and the rainbow in its emblem of grace. The figure of the woman who represents this spiritual gift holds an olive branch signifying "the peace the pardoned sinner gets through grace," while the petto, or background portion of the emblem, depicts Noah and his family kneeling in prayer beneath a rainbow as heavenly light streams down upon them. [See Baroque and Rococo Pictonal Imagery: The 1758-60 Hertel Edition of Ripa's iconsologia, ed. E. A. Maser (New York, 1971), pl. 100 (no pagination). The words quoted are by the editor, who has based them upon the commentaries in earlier editions. For other rainbows, see the plates for "Air" (8) and "Peace" (79).] The existence or such a traditional reading of the rainbow as emblem of Christian grace is not a decisive factor here, since the poetic heritage suggests the same tradition pertains to rainbows in landscape as well. The basic difference, however, is that Noah 's Sacrifice is a work of sacred history while The Seal of the Covenant and The Rainbow are landscapes.

The complicating factor arises from the fact that these landscapes make further claims to sacred history which their images for some reason will not support. The presence of the same image in two different genres, in two very different contexts, has important effects upon our reactions to it. First of all, by illustrating scriptural narrative, Maclise and Jager effectively insulate the painting's symbolism. Thus, when they depict the details and setting of Noah's sacrifice, they provided us with a representation of a wen-known scene that has a received meaning. Therefore, any scriptural references appended to their pictures simply aid the clear identification of subject. Such depiction of a traditional scene whose meaning is easily comprehended also serves to forestall any difficult questions about the artist's belief and sincerity. Although there is nothing in Noah's Sacrifice to indicate whether Maclise believed in the literal truth of biblical narrative, such matters of faith do not enter into our reaction to the picture since we have no doubts that it clearly and unambiguously offers an image of an event related in Genesis. The oldest and most basic rule of interpretation is that when one finds something puzzling or enigmatic, it is taken as a signal to search for a more complex system of meaning. Such is the [164/165] rule of St Augustine and such, if we examine it, is also the rule of modern exegesis — whether the subject be the Bible, literature, painting, or other humanistic studies. But by providing a coherent biblical context for the rainbow, these illustrations of Noah's sacrifice prevent the appearance of anything that might puzzle us and thus prompt us to look further. The information provided by these pictures, in other words, appears sufficient, and hence we do not feel impelled to search for new questions or new answers. Perhaps paradoxically, Maclise's painting, like the illustration of Jager, insulates itself from the world of the spectator because it follows the biblical text so closely.

These two pictures insulate the symbolism of the rainbow specifically because they restrict themselyes to depicting a single event that took place in the ancient past: Noah, we realize, will never again offer his sacrifice to God beneath the appearance of the world 's first rainbow. The paintings by Linnell and Grimshaw, in contrast, are both historical and predictive. They are historical because they ostensibly portray the artists' own encounters with the phenomenon of the rainbow in an English landscape, and they are predictive because they claim that these and an other rainbows, now and in the future, bear sacred significance. Whereas Maclise's painting makes no assertion about any sacramental significance of any rainbows we might see, those by Grimshaw and Linnell claim that an everyday event remains within the context of Biblical history and must be read according to the codes it supplies.

Since the arts have always been praised for their universality, one might perhaps wonder why the more generalized claim of these artists resulted in such problematic, such ineffective, art. The answer seems obvious: our own experience of landscape win not permit us to accept their particular claims about the universal spiritual significance of the rainbow. Like most obvious answers, this one is deceptively simple, for what is at issue here is a complicated mixture of changed attitudes towards art, nature, and faith. To begin with, Linnell's The Rainbow and Grimshaw's The Seal of the Covenant force the spectator to confront the nature of his religious belief. The extreme claims they make for the sacramental aspect of the universe coincide directly with Victorian and modern doubts about both the divine origins of the Bible and the presence of divinity in nature. Whereas to Newman and Keble, who both believe that a still immanent God fills nature with types and symbols, and the sudden [165/166] appearance of the rainbow is a wonderful indication of His love for man, to many other nineteenth-century poets the rapid disappearance of this heavenly bow is what matters. Thus, in both Shelley's 'When the Lamp is Shattered' and his 'Hymn to Intellectual Beauty' he sees the rainbow as an emblem of transience, and even the devout Wordsworth in the 'Immortality Ode' takes the fact that the 'Rainbow comes and goes' to be a sign of our earthly state. Similarly, in Tennyson's Becket the rainbow will not stay but disappears as quickly as it came.

Like Byron, Shelley mocks the conventional notions of rainbow and covenant. Rather than deflating them in a comic poem, as Byron does in the second canto of Don Juan he makes use of them in the blasphemous parody of Queen Mab.

Yes! I have seen God's worshippers unsheathe

The sword of His revenge, when grace descended,

Confirming an unnatural impulses,

To sanctify their desolating defects;

And frantic priests waved the ill-omened cross

O'er the unhappy earth: then shone the sun

On showers of gore from the upflashing steel

Of safe assassination, and an crime

Made stingless by the Spirits of the Lord,

And blood-red rainbows canopied the land. [pt 7, ll. 225-34]

Granted, these shrill lines furnish an extreme example of a nineteenth-century poet rejecting the Christian belief that sounds the traditional symbolic import of the rainbow. nonetheless, they do suggest how difficult it would be for later authors to employ the rainbow literally as a divinely intended emblem of grace. Shelley's parodic inversion of the traditional significance of this symbol, like Doré's and Turner's representations of the Deluge, reveals that ethical objections played an important role in nineteenth-century loss of belief. Equally crucial, of course, were the many intellectual objections fostered by geology, biology, and comparative philology since by casting doubt upon the veracity of the Scriptures, these necessarily made it difficult to take the rainbow as a divinely instituted covenant-sign. Furthermore, the discoveries of Newton, as Keats felt, "destroyed an the poetry of the rainbow by reducing it to the prismatic colours." [Miriam Allott quotes the poet's agreement with Charles Lamb as a note to "Lamia" in her edition of the Poems in thc Longmans Annotated English Poets series (London, 1970), p. 615n. She also suggests, mistakenly I think, that Keats in Lamia refers to the rainbow in Revelation 4: 2-3, but since that second rainbow (which is an arstitype of ttle one in Genesis) has not yet come into existence, it must refer to the first seal of the covenant.]

The poets of the previous century [166/167] had been moved to wonder by the divine order Newton's Optics had revealed. [In Newton Demands the Muse: Newton's "Opticks" and the Eighteenth-Century Poets (Princeton, 1946), Marjorie Hope Nicolson examines the stimulating effect Newton's discoveries had upon earlier writers.] But by the time the first Romantic generation arrived this sense of wonder had dissipated; the poets mourned the loss of mystery.

Do not an charms fly

At the mere touch of cold philosophy?

There was an awful rainbow once in heaven:

We know her woof, her texture; she is given

In the dun catalogue of common things.

Philosophy will clip an Angel's wings,

Conquer an mysteries by rule and line,

Empty and haunted air and gnomed mine —

Unweave a rainbow. ["Lamia," pt 2, ll. 229-37]

By the time that Grimshaw and Linnell painted their pictures, it was a commonplace that natural science had taken the joy and wonder from the rainbow. As Ruskin, who so frequently tried to bridge a scientific and religious conception of nature, admitted, "I much question whether any one who knows optics, however religious he may be, can feel in equal degree the pleasure or reverence which an unlettered peasant may feel at the sight of a rainbow" ("The Moral Landscape," Modern Painters, vol. 3).

These changing attitudes toward god and nature made it very difficult for most nineteenth-century writers to take the rainbow literary as Cod's seal of the covenant. Unlike Byron and Shelley, few Victorian poets were likely to take such pleasure in directly confuting or mocking the religious tradition upon which this symbolism had been based. Instead they exercise other options: first of all, they can, like Tennyson, Browning, and many other nineteenth-century authors, simply employ the rainbow at times as a beautiful optical phenomenon. Second, they can find some literary device to insulate it from questions of belief; and third, they can make use of the rainbow precisely because it is problematic, thus employing it as a paradigm of man's experience of having to make sense of an often puzzling world.

By insulating or bracketing the symbol, authors can draw upon its traditional associations and yet not make any commitment. There are many different methods of thus bracketing the rainbow and similar symbols with religious or other problematic associations. First, the writer can make an allusion, or have a character do so, in [167/168] such away as to employ the traditional meanings for somte purpose, such as delineating character, without himself admitting to any particular belief. For instance, in The Ring and Book Guido tells us much about himself when he laments that Pompilia did not come to him "rainbowed about with riches" (bk II, l. 2, 130), for to him grace, luck, and wealth are an pretty much the same; and he is incapable of comprehending the meaning of grace, much less of covenant or moral law. This effective allusion, which thus tens us a great deal about Guido, tells us little about what Browning himself believes. An additional reason for this insulating effect is that Browning here characteristically places his allusion in the mouth of a character.

A second form of bracketing the rainbow appears when writers employ it as an analogy. In Hopkins's "The Caged Skylark," at which we have already looked, the poet, who almost certainly believed in the traditional interpretation of the rainbow himself, yet insulates his image to make it more rhetorically effective. In this manner he forestalls any adverse reaction on the part of his reader. In contrast, Tennyson's "The Two Voices" exemplifies a poem that draws upon the rainbow as emblem of hope and grace without having to admit literal belief in it. At the close of his debate with the voice of doubt, the speaker victoriously asserts that it had failed to "wreck" his "mortal ark" (1. 390) and as a reward for this spiritual triumph he finds himself able to hear the voice of hope.

From out my sullen heart a power

Broke, like a rainbow from the shower,

To feel, although no tongue can prove,

That every cloud, that spreads above

And veileth love, itself is love. [ll. 443-7]

Significantly, only after this battle has been won can he walk forth amid nature¹s bounty, becoming however briefly a Wordsworthian: for he must bring his vision and faith to nature before it can offer him anything of value. Tennyson here draws upon an the traditional meanings of the rainbow as emblem of hope and grace, and he connects it to the Deluge. But he uses the traditional significances of the rainbow, as he uses the image from nature itself, as a simile and not as a fact, not as something in which he literally believes.

Placing the rainbow within fantasy, allegory, or visionary experience [168/169] offers yet another way of bracketing this symbol. George MacDonald's "The Golden Key," one of the most beautiful of an nineteenth-century fantasies, well exemplifies how effectively such traditional imagery can function within the closed world of the imaginative vision. Using the form of the fairy tale, this fantasy provides us with an allegory of human life which is at once mysterious, easy to understand, and deeply moving. After the two children Tangle and Mossy grow into adulthood, age, and die, they return to earth. But having found the mysterious door's key, which is imagination and belief, they pass through it into the rainbow:

Tangle went up. Mossy followed. The door closed behind them. They climbed out of the earth; and, still climbing, rose above it. They were in the rainbow. Far abroad, over ocean and land, they could see through its transparent walls the earth beneath their feet. Stairs beside stairs wound up together, and beautiful beings of an ages climbed along with them. They knew that they were going up to the country whence the shadows fall.

Clearly, in MacDonald's delicate allegory the rainbow is Christ and a Jacob's ladder that connects heaven and earth, eternity and time. MacDonald, a clergyman who gave up his parish because of problems of belief, here found an accessible and yet deeply personal means of drawing upon the Christian tradition.

Browning's "Christmas Eve" exemplifies another effective use of this image within a vision. In this poem Browning's speaker has taken shelter from the rain in an Evangelical chapel, and he finds himself so annoyed by the narrow sectarian zeal of the preacher and his congregation that he returns to the rainy night. He thereupon catches sight of "a moon-rainbow, vast and perfect,/ From heaven to earth extending" (sec. 6), and he rejoices that

This sight was shown me, there and then, —

Me, one out of a world of men,

Singled forth....

With upturned eyes, I felt my brain

Glutted with the glory, blazing

Throughout its whole mass, over and under

Until at length it burst asunder [169/170]

And out of it bodily there streamed

The too-much glory. [sec. 7]

At first convinced that God has vouchsafed this vision of the rainbow to him as a reward for his broader, more charitable faith, he becomes terrified when, catching sight of Christ — "He himself with his human air" — he realizes that his Saviour has turned His back on him and is walking away. Begging forgiveness, he catches hold of Christ's robe and is carried to several scenes each of which teaches him to respect belief. Suddenly he awakens again in the chapel, discovering that he has apparently not left it in body but has been dreaming. Thus Browning triply brackets his rainbow: he places it within the experience of a character who relates a vision that turns out to have been a mere dream — or was it? However ironic was his first understanding of the rainbow, the speaker was yet essentially correct since it did come to him, by whatever means, as a form of grace and it did succeed in changing his life.

Such use of rainbows in fairy tales, visions, and fantasies became a Victorian convention — a way of asserting the miraculous and wonderful in nature without having to believe literally that it was really there. Mrs S. C. Hall's "Midsummer Eve: A Fairy Tale of Love" (1849) thus rewards the selfless devotion of her woodcutter with a vision of a rainbow, which promises hope and joy. [The Art-Union Journal, 9 (1847), p. 286.] Significantly, the landscape with a rainbow used to illustrate this episode functions quite convincingly since the reader has adapted himself to the world of fantasy. Another means of similarly employing the rainbow appears in the poems of Gerald Massey, a minor Victorian author who was almost addicted to this symbol. Showing the strong impress of eighteenth-century verse, his "Lines to My Wife" and "The Ballad of Babe Christabel" make it part of personification allegories, while many of his other works use elaborate allusion to the scriptural narrative on which traditional interpretation of the rainbow was based.

All these various devices isolate the symbol within a linguistic structure, thus forestalling any questions of belief. A third major use of the rainbow appears in the poems of Tennyson where he employs it precisely because of its problematic nature. For example, "The Coming of Arthur," which proceeds by means of a series of conversion experiences that authenticate the young monarch as true king, fittingly uses the rainbow to convey the complex, personal way people attain to belief. In answer to Bellicent's query about Arthur's authenticity, Merlin replies in "riddling triplets of old time": [170/171]

Rain, rain, and sun! a rainbow in the sky!

A young man will be wiser by and by;

An old man's wit may wander ere he die.

Rain, Rain, and sun! a rainbow on the lea!

And truth is this to me, and that to thee:

And truth or clothed or naked let it be.

Rain, sun, and rain! and the free blossom blows;

Sun, rain, and sun! and where is he who knows?

From the great deep to the great deep he goes. [ll. 402-10]

About this riddling reply Tennyson himself commented that "Truth appears in different guise to divers persons. The one fact is that man comes from the great deep and returns to it" [Poems, ed. Ricks, 1480]. And one may add that in the presence of the great facts of birth and death, Tennyson sees all else as ridden through by doubt and comprehensible only by acts of belief, acts of faith. Tennyson himself can decide that nature red in tooth and claw is yet suffused with a God of love, a God Who will assist us to a higher evolution of spirit and being. The rainbow, problematic and yet beautiful, wen expresses his own attitudes towards nature.

He was able to achieve an optimistic poem in In Memoriam, which dramatizes his own experience of faith, doubt, and authentication of belief, but he presents the opposite side of the coin in the Idylls, which shows a society falling apart because men have such essential difficulties in having and keeping faith. So, too, in his other poems he presents the rainbow as potentially deluding. In "The Voyage of Maeldune," for example, the ship passes over the city under the sea, and some of the mariners are destroyed by its vision of beauty and promise:

Over that undersea isle, where the water is clearer than air:

Down we looked: what a garden! O bliss, what a Paradise there!

Towers of a happier time, low down in a rainbow deep

Silent palaces, quiet fields of eternal sleep!

And three of the gentlest and best of my people, what'er I could

say, Plunged head down in the sea, and the Paradise trembled away.

[ll. 77-82]

These lines, like Merlin's riddle, perhaps present just as dark a vision of things as does Shelley's Queen Mab, but there is a major difference: whereas Shelley sees malignant men harming other men, and Byron sees an indifferent nature devouring helpless men, Tennyson sees a sphinx-like, dangerous, but ultimately far more mysterious, external world. He fights neither the Romantic battle to see the earth as a garment of God nor that other Romantic battle to deny such a claim for he is more concerned to suggest and dramatize man's experience of a puzzling, potentially destructive, and yet frequently beautiful nature. This nature may yet be a garment of God, but it so it is one that veils as much as it reveals of the divine form. If it is an accommodation to postlapsarian man's limited senses, it is one that confuses as much as it informs, which mocks as much as it consoles and offers hope. Nature, like God, has become something wholly Other, and faith must help us see the rainbow. In other words, for Tennyson the rainbow must become as much a visionary as a visual phenomenon, because we must perceive its meaning and relevance with the eye of faith. It is not surprising, therefore, that he composed no Victorian equivalent to Wordsworth's "My heart leaps up" because for him it is not the experience of natural fact, or nature itself, which counts.

But in a rainbow landscape, such as those of Grimshaw and Linnell, it is precisely that visual experience of nature which counts and which so commands our attention. Changing attitudes towards the relation of man, God, and nature forced Victorian poets to resort to various formal verbal devices that effectively bracket the symbol of the rainbow. Such verbal devices were not available to the painter, and their visual analogues are considerably less effective. The crucial point here is that a verbal description of a rainbow can easily be contained, insulated, or bracketed because it remains a linguistic statement about a visual object, while a pictorial representation of a rainbow is simply too obtrusive. Furthermore, whereas the drive toward realism in poetry leads to emphasis upon subjective, phenomenological experience of nature, in painting it leads in the contrary direction. As Kermit S. Champa has pointed out in Studies in Early Impressionism,

Realism, or the commitment to defining pictorial effects directly visible in nature, . . . inevitably emphasizes the visual importance of the image itself and isolates it from whatever literary values it may hope to convey. Realism ruptures the balance between formal and literary intention that stands as the highest ideal in Western painting from Giotto to Delacroix. [(New Haven, l973), pp. 1-2.]

[172/173] Champa goes on to remark that it was landscape painting that "demonstrated more successfully than any other branch of painting a growing independence of subject matter from the literary issues of traditional Western imagery." Such independence, we may observe, particularly characterizes many rainbow landscapes. In fact, the large majority of such pictures painted in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries simply turn their back on the traditional iconography of this image, allowing the spectator to bring his own associations, if any, to the scenes they present. Ford Madox Brown's Walton-on-the-Naze (1860, Birmingham City Art Galleries), Claude Monet's Jetty at Le Havre (c. 1868, Marlborough Galleries, N.Y.), Turner's Buttermere Lake (1798, Tate Gallery), and many other paintings and watercolours exemplify the use of the rainbow merely as a visual motif.2 Such pictures of the rainbow of course do not originate in the nineteenth century or even in the eighteenth, since it has apparently long been the essence of the landscape painting to assert the independent existence of nature. The landscape with a double rainbow by Anaert van Everdingen (1621?-75) at Minneapolis, like the famous Rubens landscape in the Wallace Collection, exemplifies such tendencies.

Therefore: when Grimshaw and Linnell assert that their rainbows bear a sacred meaning, they are going not only against intellectual and spiritual currents of the nineteenth century but also against what had come to be dominant expectations about landscape art. These are not the only Victorian artists to make such unfashionable and even anachronistic uses of the rainbow. John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, two founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, also do so, and the reasons for their greater success tens us some interesting things about how one could employ such potentially problematic symbolism in the visual arts. But before we look at their pictures, we would do well to examine Jacob van Ruisdael's Jewish Cemetery (1660, Detroit), in which the Christian symbolism is quite clear. In the centre foreground of the painting Ruisdael has placed a tomb on which light falls, making it one of the most obvious features in the canvas. Looking back into the picture space, we then come upon the rainbow which provides an obvious visual as well as theological contrast to this whited sepulchre. It seems clear that the artist opposes the Old Dispensation to the New, the law of death to that of life, the way of Moses to that of Christ. What Ruisdael's Jewish Cemetery suggests is that for an artist to [173/174] indicate that this rainbow bears a religious significance, he must deploy at least one other obvious symbolical element. In other words, a picture must contains at least two different signals or bits of information which can direct us to read it in symbolic terms.

Such is precisely the method of Millais's The Blind Girl (1854-6, Birmingham City Art Galleries), in which the butterfly, traditional emblem of the soul, indicates to the spectator that he is to take the rainbow symbolically as well. The young girl sits with her back to the rainbow, oblivious of the beauties that have captivated the artist, while the younger child, who is her companion and guide, looks back at the glorious sight behind them. Millais thus asserts that in the better world to come, Christ will raise the blind girl with new and better vision — an action that will be an antitype or fulfilment of His earlier restoration of sight to the blind recorded in the Gospels. Again, only the presence of the second image of the butterfly persuades us that the painter intends us to read the rainbow as a sign of the Christian dispensation.

William Holman Hunt far less successfully uses a similar concatenation of religious symbols in his first version of The Scapegoat (1854, Manchester City Art Gallery). In this remarkably poor picture the goat, who stands as a type of Christ, is juxtaposed to the rainbow, another prefiguration of Christ and His dispensation. What is particularly interesting here is that we know the artist in fact encountered a rainbow on his first sight of Osdoom, the Dead Sea setting of the picture. The painter's decision to use a white, rather than a black, animal for the final version of The Scapegoat (1854-6, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight) may have furnished one reason for his decision to abandon the rainbow. Another, more important, was that, thus contrasted, the symbols do not function very coherently: whereas the rainbow in Millais's painting promises hope and salvation to the blind girl, in Hunt's picture it seems to do so to the goat. Since the point of the picture is to record the horrifying sufferings of Christ as they were prefigured in an Old Testament ritual, such an implication had to be removed. In fact, even if we read the rainbow as a promise to the spectator, it still interferes with the chief intention of the painting.

This iconological principle, that the picture must contain a second pictorial symbol to signal that we are to take the rainbow symbolically appears in some works of the American contemporaries of Hunt and Millais. Drawing upon a [174/175] political and religious tradition that dates back to the seventeenth-century Puritan settlers, American landscape painters frequently conceive of the American landscape as a new Eden or Promised Land Of Canaan. Within this context the rainbow therefore becomes an emblem of Manifest Destiny or God's new covenant with the United States. Such an interpretation of the motif appears necessary for its appearance in Frederic E. Church's Rainy Season in the Tropics (1886, J. W. Mittendorf Coll.) and his Niagara (1857, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). Paintings of Niagara Falls, which for many artists was an emblem of the United States, present us with another problem since rainbows, after an, are a constant feature of this natural landmark. Samuel F. B. Morse's Niagara Falls from Table Rock (1835, Boston Museum of Fine Arts) and George Inness's Niagara Falls (1893, Hirshorn Coll.) make use of the same motifs apparently with the same symbolical intention, just as does the latter artist's Delaware Water Gap (1861, Metropolitan Museum of Art, N.Y.). Nonetheless, this apparently conventional interpretation of the American land creates problems, for what are we to make of Inness's Etretat, Normandy (1877, Campanile Gallery, Chicago), a rainbow landscape where such a religio-political tradition doesn't apply? Because of its peculiar circumstances, American landscape painting asserted its independence of traditional pictorial symbolism far more slowly than did that of contemporary England. [For much of the information in this paragraph I am indebted to David C. Huntington, The Landscapes of Frederic Edward Church (New York, 1966). Mason I. Lowance, "Typology and Millennial Eschatology in Early New England," Literary Uses of Typology fom the Late Middle Ages to the Present, ed. Earl Miner (Princeton, 1977), pp. 228-73, contains the essential background for such an interpretation of American painting.]

Within this kind of nationalistic tradition to provide a defining context, the rainbow motif in English and American painting became increasingly difficult to employ without uncontrolled ambiguities. Occasionally one comes upon an idiosyncratic religious symbolism, such as Helmut Borsch-Supan finds in the rainbow landscapes of Caspar David Friedrich,3 but most nineteenth-century artists painted the rainbow, as they painted other natural phenomena, as something upon which human beings could no longer impose their own meanings. Only rarely do we encounter works of visual art which make use of this problematic imagery and symbolism precisely because it is problematic. Significantly, the few pictures that incorporate the rainbow motif in this manner juxtapose it to the idea of shipwreck — in essence thereby making secular commentary upon the originally paradigmatic connection of the Noachian Flood and the rainbow that God placed in the heavens after the patriarch's sacrifice to Him.

Francis Danby's last painting, recently rediscovered after being [175/176] lost for many years exemplifies such a juxtaposition of rainbow and sea disaster. The artist sent his untitled work to the 1860 Royal Academy exhibition with an unidentified epigraph:

When even on the brink of wild despair,

The famish'd mariner still firmly looks to thee,

And plies with fainting hand and broken oar;

While o'er the shatter'd ship thy arc is spann'd,

Though an alas! seems lost, still there is HOPE.

There is hope, yes, but is it delusive? A contemporary review in the 1860 Art-Journal commented that "Mr. Danby leaves the title to the taste of the visitor, who, rather than resolve it into 'a shipwreck,' will determine it as "Hope"; for amid the turmoil of the elements, a rainbow appears in the sky." [vol. 22 , p.169.] Such an optimistic reading of Danby's last work seems clearly disproved by the recent discovery by David Rodgers, who identified the long-lost picture, that the wrecked vessel bore the name Hope. ["HOPE rediscovered, a shipwreck by Francis Danby," Burlingtorn Magazine 121 (1979), 584]. Rodgers, whose discoveries confirm my earlier speculations in Nature and the Victoran Imagination (1977) that the lost painting employed the rainbow ironically, does not, however, accept that the ambiguities in Danby's picture are intentional, and he concludes that they are simply the result of the artist's ineptitude. Rodgers argues that the painting is therefore likely to be an analogue to Friedrich's lost The Wreck of the "Hope", and one may add that the contrast of the rainbow and the doomed vessel Hope functions to emphasize both how harsh nature is to man and also how little one can believe supposedly divine promises impressed upon her. Had the artist given some indication that the rainbow symbolizes hope of salvation and the ship earthly hope, one might have been able to argue that he was contrasting true versus false hope, that of salvation versus earthly safety, but, in fact, nothing in the painting or epigraph encourages the spectator to take the picture thus as an analogue to Thoreau's Christian interpretation of the shipwreck on Cape Cod. Like the rainbows in Byron and Turner, this one seems to embody a Fallacy of hope.

Turner, painter of many shipwrecks and many rainbows, opposes the two motifs in The Wreck Buoy (1849, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool). In this picture the juxtaposition of the two ideas functions as it does in Danby's later painting of the destruction of the Hope. As the Art Journal review made clear, when one looks at a shipwreck with a rainbow, one first reacts to the disaster itself — it dominates the canvas — and only later does one qualify it by the presence of the rainbow. Turner's painting makes us proceed in the opposite direction, as it were, since we first catch sight of the rainbow, a potential emblem of grace and hope. Only then do we move from [176/177] this most commanding element of the picture's composition and colour to the wreck buoy in the foreground, perceiving this marker placed to warn ships away from sunken hulks that might destroy them. In Turner's painting, then, the rainbow as emblem of hope is qualified and rendered ambiguous by juxtaposition to the idea of disaster. The artist, in other words, seems to be directing us to guard ourselves against all kinds of fallacious hopes, whether spiritual or secular. He therefore makes this picture, like so many others in the series connected to his poem 'The Fallacies of Hope', into a kind of wreck buoy that can warn others against the dangers of illusion.4 In his version of the rainbow's first appearance to man — Light and Colour (Goethe) through) The Morning after the Deluge Moses Writing the Book of Genesis (1843, Tate Gallery) — he also qualifies the traditional symbolism of this natural phenomenon. His epigraph tens us that when the sun appeared after the "ark stood firm on Ararat," it brought with it

in prismatic guise

Hope's harbinger, ephemeral as the summer fly

Which rises, flits, expands and dies.

Turner, who spans the Romantic and early Victorian years both spiritually and chronologically, Finally believes that to see nature's rainbow as an emblem of hope is itself one of the great Fallacies of Hope: it is to believe, as Grimshaw and Linnell apparently did, that God marked nature with signs for the sake of man; it is to believe that man finds in nature meanings that he himself has hidden there — and finds them to be true. Like Tennyson and Browning, Turner realizes that the "thoughtful eye" demanded by Fairbairn no longer can see in this optical phenomenon an unambiguous covenant-sign. Like these poets, he transforms the rainbow into a powerful symbol of man's problematic relation to problematic nature.

A postscript to rainbows

Since, like unicorns, rainbows have become an extraordinarily popular decorative motif in American popular culture of the late 1970s and early 1980s, one cannot stop the tale here. One encounters rainbows on wall-hangings, posters, teapots, key chains, jewellery, [177/178] writing paper, tote bags, mobiles, woven fabrics, and virtually anything else upon which the colours can be applied. Thom Klika, 'the Rainbow Man' from Woodstock, N.Y., has done much to popularize the motif in paintings, books, and decorative arts, and in his work it appears more as a general image of nature's beauty and man's hope. Occasionally, as in the objects either created or simply distributed by the Abbey Press, which is owned by the Benedictine St Meinrad Archabbey, the rainbow receives its traditional Christian significance, but such is generally rare.

The contemporary American painter John Shroeder, on the other hand, employs the rainbow to make his characteristically ironic, sceptical commentaries on traditional religious solutions to the problem of pain and evil, and he emphasizes precisely this problematic, ambiguous nature. Many of his works, which he describes as "metaphysical cartoons," are peopled with strange and delightful combinations of characters from the Bible, classical myth, and contemporary and earlier American culture. For example, in Country Dance with Sky Clowns (1977, private coll.) the angelic visitants appear as flying circus entertainers; and in the recent The Same old Thing (1980, Joan Barrows. Carter Coll.), a representation of the Fan, the guardian angels, who have not done a particularly effective job, appear as Keystone Cops. Many of Shroeder's paintings embody the structure of the situation of crisis in which helpless human beings find themselves surrounded and threatened by powerful forces, usuany invaders, which promise to destroy them. His Parable of the Rainbow Dancers (1975, private coll.) presents Adam and Eve, who have been wandering around Eden wen before the Fan, finding themselves surrounded by pirates from outer space. As the artist explained in a description of this work written for one of its exhibitions, "Job's Comforters, Eliphas, Bildad, and Zophar, touring the Garden of Eden as God's guests, see the Space Pirates menacing Adam and Eve," and horrified, they anxiously inquire of the Lord 'the great question', how can He now such things to happen? Why, when we do nothing wrong, does He permit suffering to fall upon us and not upon evil-doers who deserve it? Instead of answering this question directly, however, God

sprouts from the palm of his hand the Parable of the Rainbow Dancers. Suffering, the parable asserts, is of no consequence. God allows us to suffer undeservedly because, in the long [178/179] view, it doesn't matter, it isn't worth his worrying about. Good and Bad, virtuous and wicked, Innocents and Space Pirates, we shall an alike in our perfected forms be dancers of rainbows, and the memory of our earthly sorrows will be but as mist in the hot sun.

Such might be a devoutly Christian reading of the rainbow, the problem of evil, and the nature of man's eternal place in the universe. Shroeder, however, completes his description of The Parable of the Rainbow Dancers by indicating that God, somehow, has not been very candid with poor Eliphas, Bildad, and Zophar — much less with Adam and Eve: 'As the Duke of Wellington remarked to a man who approached him saying "Mr. Smith, I believe," "If you can believe that, you can believe anything!" Rainbows in Shroeder's imaginative world here turn out to be not just potentially misleading and ambiguous but intentionally so.

Last modified 18 February 2019