All illustrations except the first come from our own website. Click on them for more information about them, and to see larger versions of them. — JB

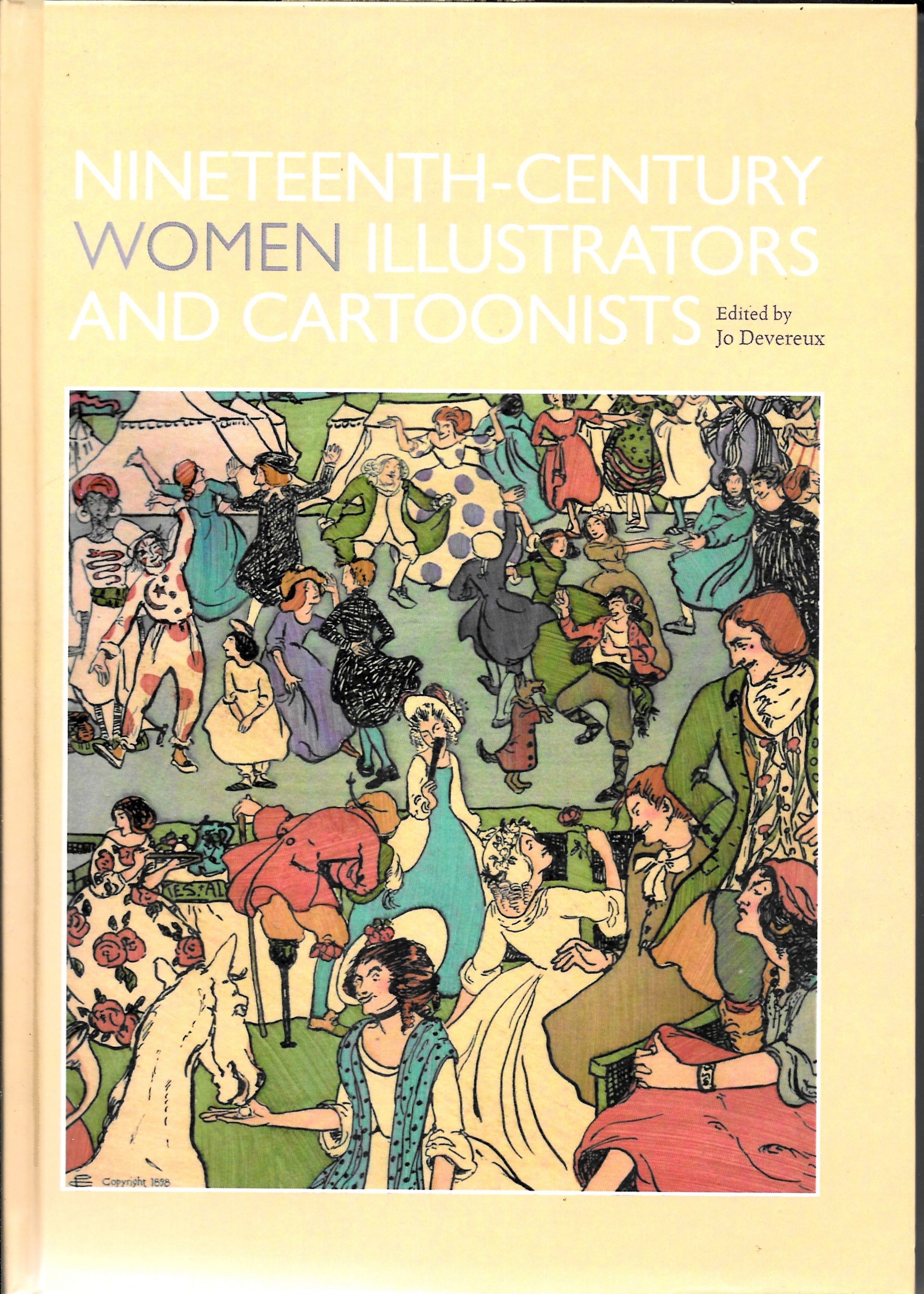

This is a valuable collection of fourteen essays on a range of artists of great gifts, who have been somewhat forgotten or even ignored by mainstream art history.

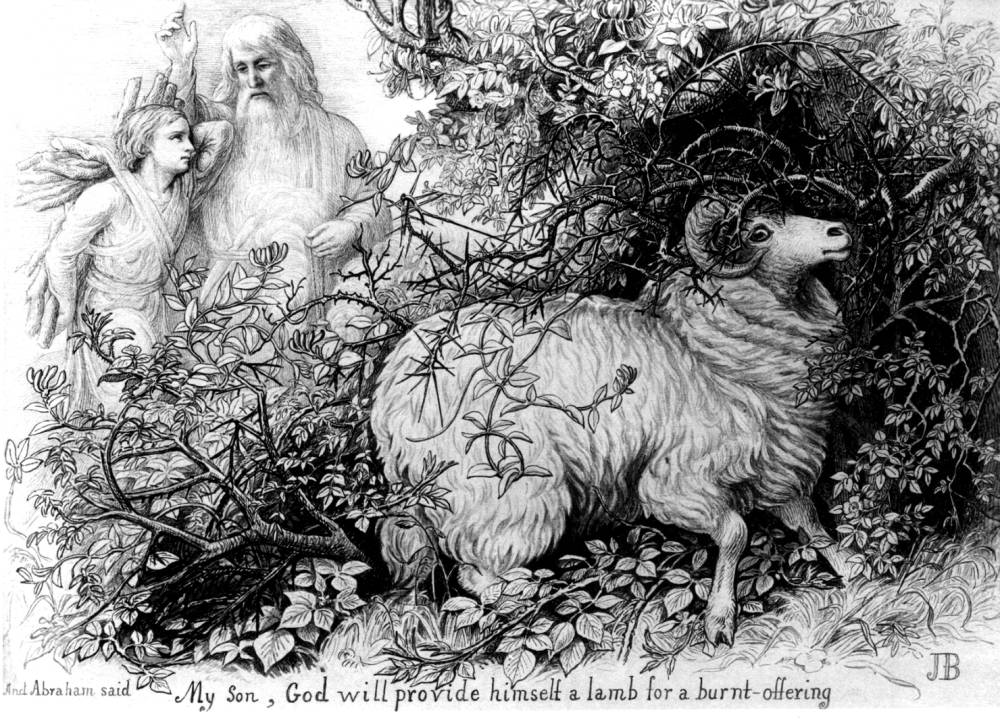

The first three chapters are devoted to natural history illustration, 1855–1890, and here Bethan Stevens views the illustrator Jemima Blackburn as an expert in ornithology; Blackburn's studies of the cuckoo were inspired by the writings of John Gould and Charles Darwin. She was also influenced by Bewick and this can be seen quite clearly in The History of Sir Thomas Thumb in 1855 where she adopts his use of the tail-piece for a closely observed depiction of a cow. Before this came Illustrations of Scripture by an Animal Painter (1854) for which she made twenty-two drawings. Notable designs are of a trapped sheep and a raven: both are striking and original. The emphasis is frequently on the horrific and these designs attracted the attention of Ruskin who encouraged Blackburn to think about illustrating Dante. This suggestion was not followed up but the fact that Ruskin noted her illustrations shows that her work was profound, and deserved to be taken seriously.

Left: Jemima Blackburn's "The Ram Caught in the Thicket" (1886). Right: Eleanor Vere Boye's "Tommelise Borne on the Swallow's Back" for Andersen's Fairy Tales (1872).

Eleanor Vere Boyle illustrated children's books such as Beauty and the Beast: An Old Tale New-Told (1875) and was also admired for her garden books, notably Days and Hours in a Garden (1884) and A Garden of Pleasure of 1895. Her designs in these publications reveal her as influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites, with a pronounced empathy for the natural world. As suggested by Laurence Talairach in Chapter 2, her designs are linked with horticultural imperialism and exotic plants that relate to Victorian notions of empire. She also made full use of colour, especially in Beauty and The Beast, where the designs are splendid and impressive; it might have been useful to be told which method of reproduction was used in every case.

In Nancy V. Workman's chapter devoted to Marianne North we are informed that her paintings are permanently displayed in the North Gallery at Kew. She published Recollections of a Happy Life (1892) – two volumes of autobiography – but she seems to be seen as primarily a painter rather than a book illustrator, as might be expected in a work devoted to illustration itself. However, this is a useful chapter on the artist and the reader must be grateful for being enabled to see her colourful designs.

Amelia Frances Howard-Gibbon is a little-known artist, and Margo L Beggs highlights the manuscript of An Illustrated Comic Alphabet of 1859. It seems that it was never formally published in book form, but the images are well worth examining. The designs are surprisingly strong and one of the toughest is B was a Butcher who had a great dog. The suggestion is that Howard-Gibbon was perhaps inspired to produce her alphabet by General Tom Thumb by "Grandpapa Easy" (c. 1845), which is a book of coloured wood-engravings.

"Harry," she said, "There is nothing wrong between you and Florence?" by M. E. Edwards (1866) for Anthony Trollope's The Claverings.

Simon Cooke's essay on Mary Ellen Edwards is typically cogent, and he points out that she was asked to illustrate Anthony Trollope's The Claverings (Cornhill Magazine, 1866). Her designs rival those of Millais, who illustrated several other works by Trollope. That Edwards did not enjoy due recognition for this achievement is sad, to say the least. She went on to illustrate M.E. Braddon's "Birds of Prey" in the magazine Belgravia in 1867, and here we can see how her images of women come to life, exhibiting psychological depth and inner strength.

Edith Hume illustrated in The British Workwoman between 1866 and 1913. Her designs, Deborah Canavan shows, are essentially depictions of women epitomising Christian virtues in domestic settings. Hume's drawings are powerful and moving, and Canavan brings to our attention influences from Dutch art in depicting fishing communities leading honest and grim lives in desolate environments.

Nancy Marck Cantwell explains that Alice Barber Stephens is notable for her designs for an edition of George Eliot's Middlemarch which was published in 1899 by Thomas Y. Crowell in Boston. Stephens's images of Dorothea are powerful and moving and this book can be seen as a feminist statement, and one relevant to women at this time who were eager for a more central role in a patriarchal society. It is valuable to bring this striking account to our notice, and indeed this feminist orientation is echoed in most of the other contributions to this book.

Florence Caxton's "London Societies. No. I. Society for the Practice of Part-Singing." London Society 1 (April 1862).

The editor, Jo Devereux, concentrates on frames, doorways and domestic satire in the illustrations of Florence and Adelaide Claxton. Florence concentrated on images where several figures appear on a single plate, and this echoes the work of male caricaturists such as Robert Seymour and Hablôt Knight Browne (Phiz). Both sisters appeared in the pages of London Society, and it was Adelaide who made excellent designs for Riddles of Love by Sidney Blanchard, where the figures are beautifully drawn with careful connection with the text. These images are notable for putting the women in a prominent position where they dominate the male figures. The author states that the sisters left a legacy of "spirited and humorous insights,"" and again it is valuable to place these artists where they may be properly admired as equal to male illustrators of the period.

Marie Duval is an illustrator who has been largely forgotten since Victorian times but who is now visible once again as a genuinely humorous artist whose works appeared in the pages of Judy and The London Serio-Comic Journal, where she contributed many designs including cartoons and comic strips between 1869 and 1885. Analysed by Simon Grennan, Roger Sabin and Julian Waite, her style is shown to be 'untutored' and full of comic distortions and dynamic story telling which mark her out as another artist who deserves recognition.

Amy Sawer, Kate Holterhoff explains, is yet another artist who has been much forgotten but who illustrated many designs at the close of the nineteenth century. She illustrated among others the novels of Rider Haggard, with images of interest in his Heart of the World of 1895. Here Maya is seen sitting by the side of a spring, but it is sad that the reproduction here is too poor for it to sing off the page as it should. The Seasons of 1905 is seen as an art book containing twelve fine colour plates. Strangely, the two colour reproductions offered here show the same image photographed twice, one through a paper overlay and the other appearing much smaller than the other; it is clearly a work of great interest, showing the artist's skill in lithographs. The plates depict women corresponding to the months of the year with reference to flowers such as violets for January, and daffodils for March.

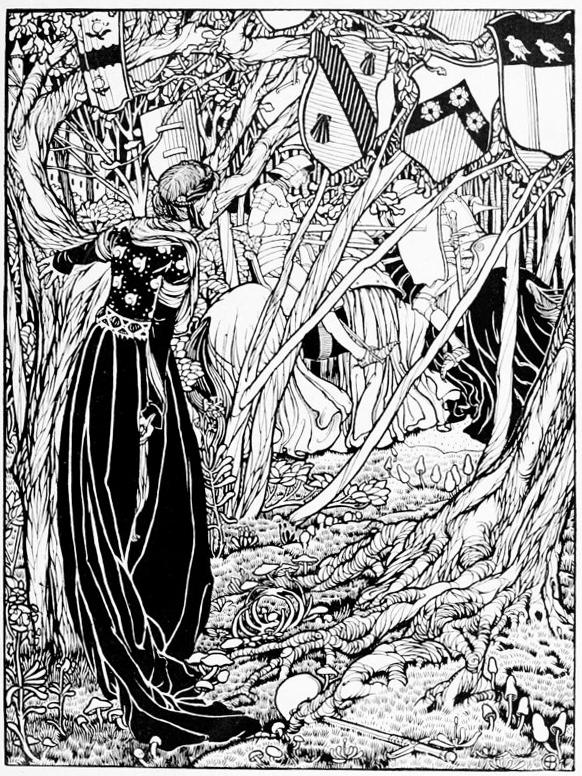

Left: "Sir Lancelot du Lake" (c.1898) in The Studio. Right: "The Gilded Apple," 1899.

Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale illustrated in black and white at the beginning of her career and Pamela Gerrish Nunn concentrates on this aspect of her work. She illustrated in Country Life and the Ladies' Field and these images sit well in conjunction with the text. Later on in her career she worked in the fin de siècle style, and these noteworthy images are frequently in full colour.

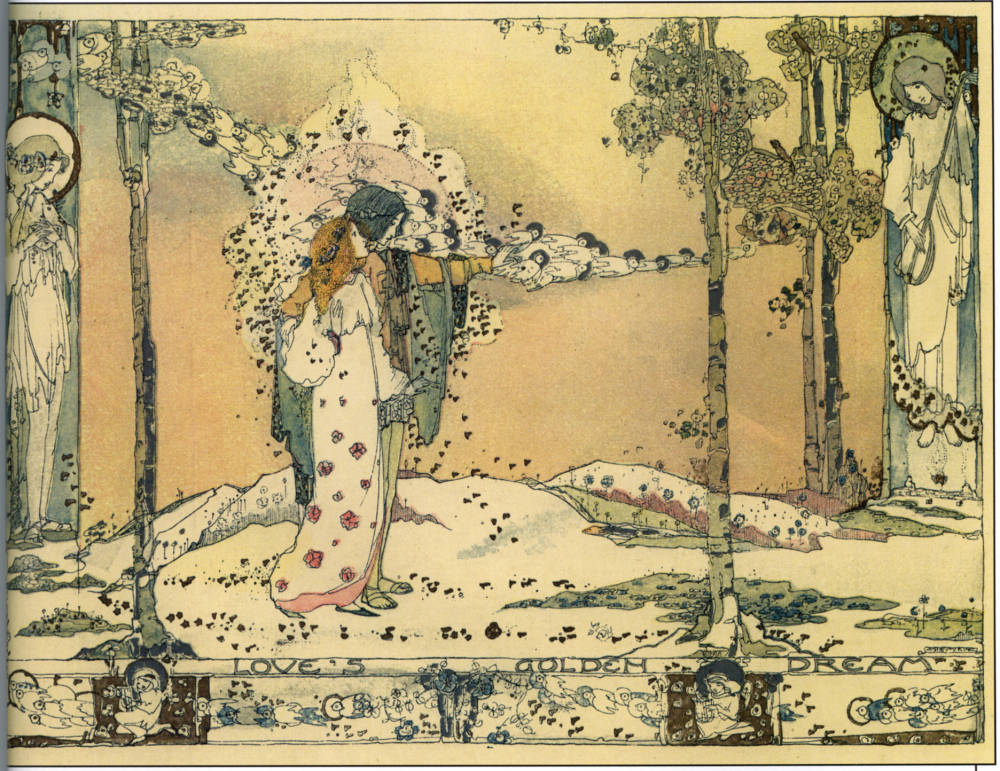

Jessie Marion King illustrated in a remarkable style which featured mysterious figures almost floating in the air; quite distinctive and memorable. Indeed, as Carey Gibbons suggests, she worked in a style which was entirely her own and completely unlike that of her fellow female artists discussed in this book. There is just one colour plate reproduced and again it is unfortunate that the reproduction is somewhat unclear. There are five further black and white reproductions in the chapter; these are rather dark and might have been shown in colour.

"Love's Golden Dream," by Jessie M. King for "Seven Happy Days" in the Christmas Supplement to Source The Studio, 1913.

Pamela Colman Smith was notable for her striking and memorable images, hand-coloured and produced using stencils using a method sometimes referred to as pochoir. In 1899 she illustrated Widdicombe Fair which is beautifully coloured and she also produced a magazine called The Green Sheaf in 1903 which reflected her interest in Irish folklore and this she edited from her London studio selling frequently directly to visitors. She was born in London in 1878 to Anglo- American parents and she studied in America and lived and worked for a time in New York. When she did not receive sufficient support there she returned to London where her work was much appreciated. Her art is so outstanding that Smith must be seen as a pioneer in hand-coloured illustration. Lorraine Janzen Kooistra and Marion Tempest Grant explore her art for the page.

Olive Allen was both a cartoonist and an illustrator who illustrated among other ventures "The Hill of Venus," a poem by William Morris in The Studio (October 1900) and a story by Maria Edgeworth called The Birthday Present (1908). She also made cartoon-like designs for Humpty Dumpty and The Princess by Lilian Timpson (1907). She emigrated from London to Canada in 1913 where she virtually left illustration and instead turned to painting landscapes as a member of the progressive Canadian School. Jaleen Grove considers this lesser-known designer.

Taken as a whole, this study is invaluable for the light it sheds on several little-known illustrators and cartoonists. However, the dim quality of several of the reproductions undermines the contributors to a serious extent.

Bibliography

Jo Devereux, ed. Nineteenth-Century Women Illustrators and Cartoonists. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2023. pp. xiv + 294. £90.00. ISBN 9781526161697

Created 20 August 2023