You may use the images from our own website without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to the relevant URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on all the images to enlarge them.

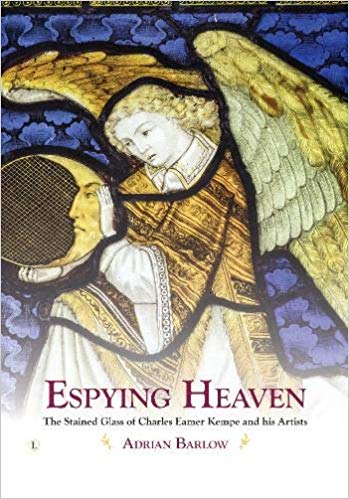

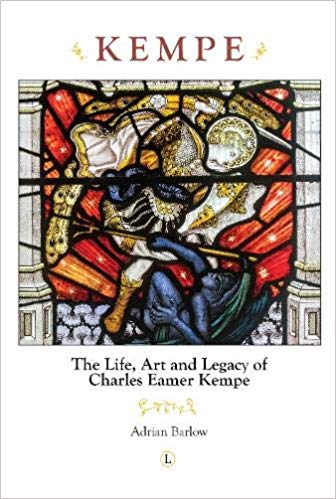

Charles Eamer Kempe ran a flourishing studio of ecclesiastical stained glass and painted decoration in up-market Marylebone during the later Victorian and early Edwardian periods. His friend A. C. Benson, whose father had been Archbishop of Canterbury, and who was well-versed in the subject, believed he probably had more influence on ecclesiastical art than anyone else of his time (Kempe, 236). Yet has he had his due from the critics? Adrian Barlow thinks not. Even Benson, for all his friendship with Kempe, privately admitted to strong reservations about his stained glass, the very work for which he is still best known: "we do not want unadulterated Kempe everywhere," he wrote in his diary (qtd. in Kempe, 238), complaining not only that all the faces in his windows were the same, but that all of them, even Mary Magdalene's, looked suspiciously like Kempe's — in this instance, though, clean-shaven. Barlow's two complementary studies, one focused on Kempe's life and art, the other specifically on his stained glass, aim not only to extend our knowledge of his subject, but to raise him in our estimation by explaining why, how, and to what effect his designs and practices differed from those of his contemporaries.

Faces of the four evangelists in the very early 16c. Evangelists Window at St Mary's, Fairford, said to have influenced Kempe as a young man. Photograph by Mattana at Wikimedia Commons (reproduced with thanks).

To begin with, Barlow uses archival material to give a much clearer picture of Kempe's boyhood, and the development of his career and style, than we have had before. In Kempe: The Life, Art and Legacy of Charles Eamer Kempe, for instance, we learn that his upper-class background was only comfortable up to a point — and an early point at that. His father, a widower who had remarried late, was getting on for eighty when he was born, and died when he was six. This, incidentally, is one of many details on which Barlow quietly corrects Kempe's previous biographer, Margaret Stravidi, who describes him as being "barely seven" then (Stravidi 14). It took years to wind up the family's country estate in Sussex, and in the meanwhile the main source of continuity in Kempe's life was school and college: first a prep school where he was unhappy, and where he started to stammer, then Rugby, where he coped much better, and then Pembroke College, Oxford, where he developed the interest in churches which would define his future. Throughout, he had no place that he could really call home, was worried about his mother's well-being while trying (not very successfully at first) to reassure her about his own, and was chronically short of funds. But his family connections, and the friends he had made along the way, came in handy as he embarked on his chosen career. On one of his outings from Oxford, he had visited St Mary's, Fairford, a church with stained glass from the period 1500-1515, which made a deep and lasting impression on him. Unable to speak from the pulpit because of his stammer, he would now begin to serve the church through enhancing its fabric, speaking and teaching more fluently through design than he ever could with words.

Specimen of the painted decoration at G. F. Bodley's All Saints, Jesus Lane, Cambridge. This was known to have been the work of Frederick Leach when he and Kempe were both working there. Photograph by Adrian Powter.

At this point in Kempe, Barlow can refer to Michael Hall's recent wide-ranging and widely acclaimed study of G. F. Bodley. As Kempe's senior by ten years, Bodley became both his mentor and his friend. Kempe collaborated with him at All Saints, Cambridge, for example, and at St John the Baptist, Tuebrook. The decoration of the Cambridge church is generally seen as a turning point in Bodley's career, a change confirmed by the lavishly decorated Tuebrook church, which, says Barlow, was "one of the decisive statements of the Aesthetic Movement" (31). When Nikolaus Pevsner says later that he worked within "the accepted High Church medium" (qtd. in Kempe, 250), he forgets the extent to which Kempe helped to establish that medium.

There was never any formal arrangement, but, by at least 1868, Kempe had his own Studio at his London address. This was the year in which he asked Frederick Leach (1837-1904), the master "art worker" of Cambridge, with whom he had worked at All Saints, to help him at Tuebrook, and then, when that was completed, to assist him with a study of stained glass of his preferred period. At that time, Leach had, as an apprentice, a young lad by the name of Alfred Tombleson (1852-1943). Leach would leave Kempe's Studio around the end of 1872, feeling that he was being treated as an inferior (in the end, he would have almost as large a workforce as Kempe himself), but Tombleson stayed as Master Glazier, managing a dedicated glassworks for Kempe in Camden, on the site now occupied by Mornington Crescent tube station.

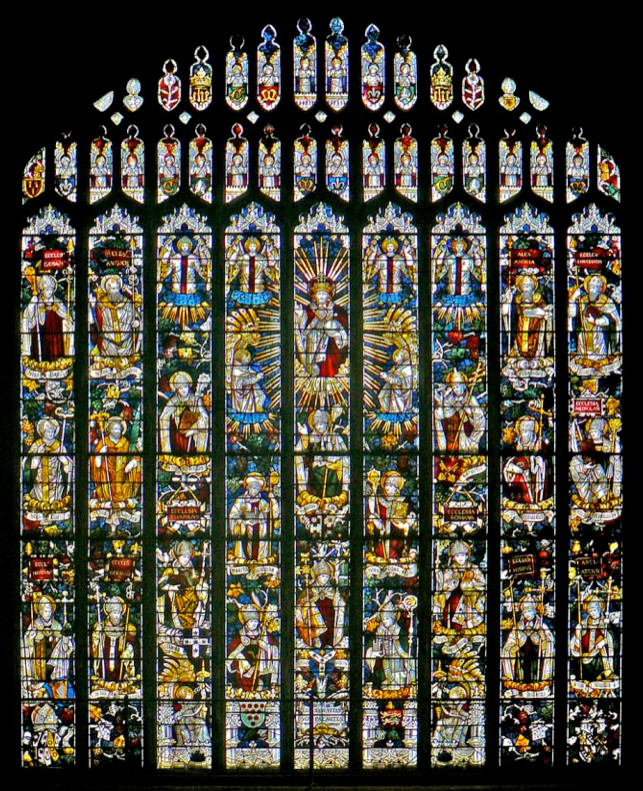

The Tree of the Church in Lichfield Cathedral. Photograph by Colin Price.

From start to finish, even when guided by one man's vision, the production of stained glass is essentially a collaborative process. In Espying Heaven, Barlow stresses his Master Glazier's vital importance to Kempe's success by looking at his role even before turning to the design work at the Studio. For his part, Kempe allowed the loyal and long-serving Tombleson to add his own monogram to a number of the outstanding later windows. As for his chief draughtsmen based in Marylebone, whom Barlow considers next, and in depth, these were John Carter (1848-1901) and Wyndham Hope Hughes (1849-1948), who did so much to establish Kempe's early style and reputation, and John William Lisle (1870-1927). Lisle, trained in stained glass design by Kempe himself, became his chief draughtsman in 1895, the very year that Barlow describes as Kempe's annus mirabilis. In Espying Heaven, he calls Lisle's first important window, "The Tree of the Church" at Lichfield Cathedral, with its twenty-two episcopal saints and its heraldic tracery, "one of the finest achievements not simply of the Studio but of nineteenth-century stained glass as a whole" (26). It is one of those windows which carry both Kempe's and Tombleson's "signatures."

Significantly, Pevsner has nothing to say about this complex and dazzling window in his Buildings of England volume about Staffordshire. He simply notes that it was made by Kempe (186). But then Pevsner had already said at the beginning of the volume that William Morris's glass was "the finest anywhere in Europe," and that, when seen side by side with it, Kempe's glass was bound to suffer (38). This book was first published in 1974, and more recent stained glass critics like Martin Harrison (Victorian Stained Glass, 1980) went on to adopt the same stance. Barlow points out, however, that the comparison is unfair: Kempe was working in a different tradition. He was a High Church Anglo-Catholic, and, despite his own lifelong respect for Morris, his preference was for an Anglican aesthetic rooted in the later medieval or early Northern Renaissance period, rather than the earlier one that appealed to Morris. For instance, says Barlow, what inspired the "well-defined cheeks, nose and chin, the wide, sensitive, expressive mouth" of his typical face was not self-regard at all, but the face of St Mark that Kempe had seen in the very early sixteenth-century glass in Fairford church (Kempe, 240).

Kempe has been misunderstood in another way too. Despite the essentially collaborative nature of his work, and the fact that he helped to decorate and furnish Wightwick Manor, an Arts and Crafts house in Staffordshire, he kept aloof from the socialist ideals and practices espoused by Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement in general. His own workforce was hierarchical, with the Studio and the glassworks quite separate from one another: however important his Master Glazier was to him, Barlow tells us, the two were never on first name terms. Was Kempe's success, then, a matter of hard-nosed commercialism? Far from it. He had spotted and brought out the potential of those who worked for him, and fostered their careers, and they responded with gratitude: "reciprocal confidence and loyalty was one of the most important factors in the enduring success of [the] whole Kempe enterprise" (Kempe, 41). This was not simply a case of a paternalistic employer and his underlings. Barlow quotes in full a letter from the Reverend Cathrew Fisher to Walter Tower, Kempe's cousin three times removed, and chosen heir. Written shortly after Kempe's death, it proposes an article about "Mr. K," in which the Reverend Fisher planned to show "how essentially a Christian teacher" he was, "and how that ran through all he did" (Kempe, 240).

Old Place, Lindfield, Kempe's home in Sussex. Photograph by John Kemp, Kempe's great-great-grandnephew.

Perhaps the best response to Kempe's critics, and the best tribute we can pay to him now, is to take our cue from those who knew him and worked for him, and see what it is he was teaching. That is exactly where Espying Heaven is most helpful, allowing us to "read" the details in his windows as well as to appreciate the artistry involved. Now both books are beautifully produced: there are numerous black and white illustrations in Kempe, showing people, places and churches connected with Kempe, including Old Place, the lovely house in Sussex that he bought and extended. Examples of his painted decoration there and elsewhere, as well as his church fittings and stained glass, abound. Kempe also has twelve colour plates of photographs by Alastair Carew-Cox. But Espying Heaven has over a hundred illustrations of his stained glass alone. These too are by Carew-Cox, all of a very high quality. They are accompanied by Barlow's lucid and well-informed discussions of them, bringing in Biblical and church history as well as examining typology, iconography, heraldic details, inscriptions, technical points (silver staining, for instance) and stylistic developments under the different draughtsmen. Especially useful are the themed discussions of groups of windows, such as those featuring the Virtues (Prudence, Fortitude and so on, as well as Faith, Hope and Charity), or the Annunciation. A wonderful moustachioed St George catches the eye, too — it is actually the Duke of Clarence as St George, designed as a memorial to him by John Lisle, and now in the Stained Glass Museum at Ely Cathedral.

Photographs will never do full justice to stained glass: nothing can replicate on the flat page the play of passing light and shade on a window's colours, or the patterns they cast on stonework or tiling around them; no photograph can convey the sense that this form of art is a part of the living here and now, which nevertheless gives a glimpse of a world beyond. This is recognised in George Herbert's "The Windows," which gave the book is its title and is quoted as an epigram to it. But these glorious photographs are the next best thing.

George Herbert, designed after Kempe's death by John Lisle, from the "Anglican Window" at All Saints, Jesus Lane, Cambridge. Photograph by Adrian Powter.

Kempe himself was a particular admirer of Herbert, and Barlow's last chapter starts with a short section on him, and the various windows in which he features. It concludes with memorial plaques to Kempe in Southwark and Chichester Cathedrals. But Kempe's story did not end when he died. His death was swiftly followed by the setting up of the private limited company of C. E. Kempe & Co., under Tower's chairmanship, and work continued until 1934 — with Tombleson still running the glassworks, well into his eighties. Demand had dwindled, and the variety and quality, even the palette, of the earlier windows had been affected. But by then Kempe and C. E. Kempe & Co. had left their mark on churches all over the country, and far beyond it. Fifty years later, the Kempe Society was founded, and the Kempe Trust continues actively to support the preservation and promotion of this work today. These books themselves were published with its help.

Note: The detailed material on Kempe is often useful for stained glass and church decoration studies in general: as well as a full bibliography and a gazetteer of Kempe windows, Kempe has a glossary of architectural and other terms (for costume, for example) used in the book. Espying Heaven also has a short glossary at the end.

Bibliography

Barlow, Adrian. Espying Heaven: The Stained Glass of Charles Eamer Kempe and His Artists. Cambridge: Lutterworth. 129 pp. £20. 978 0-7188-9464-1

_____. Kempe: The Life, Art and Legacy of Charles Eamer Kempe. Cambridge: Lutterworth. 312 pp. £25. 978 0 7188-9463-4

Pevsner, Nikolaus. Staffordshire. 1974. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002.

Stavridi, Margaret. Master of

Glass: Charles Eamer Kempe 1837-1907 and the work of his firm in

stained glass and church decoration. Hatfield, Herts.: Kempe

Society/John Taylor Book Ventures, 1988. 20 February 2019