Ray Dyer has traced Tennyson's growing importance to Lewis Carroll, as he came to fill the role of father-figure, as well as becoming the younger writer's admired "poet-bard." But now there was a cooling off in their relations. Note the form of multi-volume citations below. Diaries, I: 51-52 note 1 appears as follows: Diaries 1.51-52n1. [Click on the illustrations to enlarge them, and for more information about them where available. — JB]

A Melancholy Interregnum, 1865-1876

Following his abortive Isle of Wight summer visit of August 1864, and before Lewis Carroll sank into any kind of melancholy reflection upon his present life and changed state of friendship with Tennyson, he returned to his home life in the North of England and busied himself with other essentials. On Tuesday 13 September he was at Croft and completing the drawing of his own "pictures in the MS. copy of 'Alice's Adventures,'" which had been "first told July 4. (F). 1862." (Diaries, 5: 9). He was already resolved to have an extended version published in book form, and his surviving correspondence with the publisher Macmillan dates from 11 November this year (16n8). Back at Christ Church in October he had noted "the dull uniformity of term-work," and by 9 December wrote of "a harder-worked term than I have had for a long time," (21, 28). Relief came by Tuesday December 20, when he took the 9 a.m. train to London and found rooms in the Old Hummums hotel alongside Covent Garden market. He visited friends he had made that summer, taking them "the photographs" he had done "of the children at Freshwater". Two days later he visited other such friends, the Parkes family at Surbiton, whose children Carroll had also "met at Freshwater" (30, 37). No record is known, however, of any use made by Carroll at this time of postal or other services to the Tennysons for purposes of forwarding them relevant prints of that summer's Freshwater visit. The years 1865-69 which would follow appear to have been dormant for any active Carroll-Tennyson relationship.

At year's end Carroll was at Croft with his own family, then Whitburn with his Wilcox cousins. For Saturday 31 December 1864 his journal bears a lengthy paragraph of soul wringing - of "intense gratitude to God ... and my shame and sorrow for the sin, and coldness and hardness of heart by which I have provoked Him...." His wish was for "grace to put away the sins of the dead year, and ... to begin a holier and better life ... before I go hence, and be no more seen" (Diaries, 5: 40). He was then just two weeks away from completing 33 years of age.

1865. On Friday 10 February Carroll brought back to his Christ Church rooms his older friend Reverend John Slatter, together with Bessie Slatter (b. 1854) and their friend Edith Clifton "a pretty child of about 11, with beautiful long flaxen hair," (Diaries, 5: 48). Carroll's long-standing romantic appreciation of such feminine hair is discussed in relation to his keen interest in the paintings of girls by his contemporary, the artist Sophie Anderson, who would later produce a painting of Tennyson's tragic Elaine [see 1870]. That Carroll knew of the Poet Laureate's romantic and literary uses of the imagery of long hair may well have dated from as early as Tennyson's Poems of 1842, as earlier shown in Carroll's letter and long discussion of 20 February 1861 to his own sister Mary. There he had insisted on copying out for her "word for word" the appropriate lines from Tennyson's "The Gardener's Daughter":

A single stream of all her soft brown hair

Pour'd on one side; the shadow of the flowers

Stole all the golden gloss, and, wavering

Lovingly lower, trembled on her waist. [Cohen & Green, I: 47-49, Letter of 20 February 1861 to Mary Dodgson).

Now however, with the four good Isle of Wight years already behind him, young Edith Clifton's hair remained in a relative scarcity of the personal associations which Lewis Carroll was able to endure, and no further whisper of the older poet-idol seems to have been permitted [see Carroll-Tennyson Chronology, Part II, 1864].

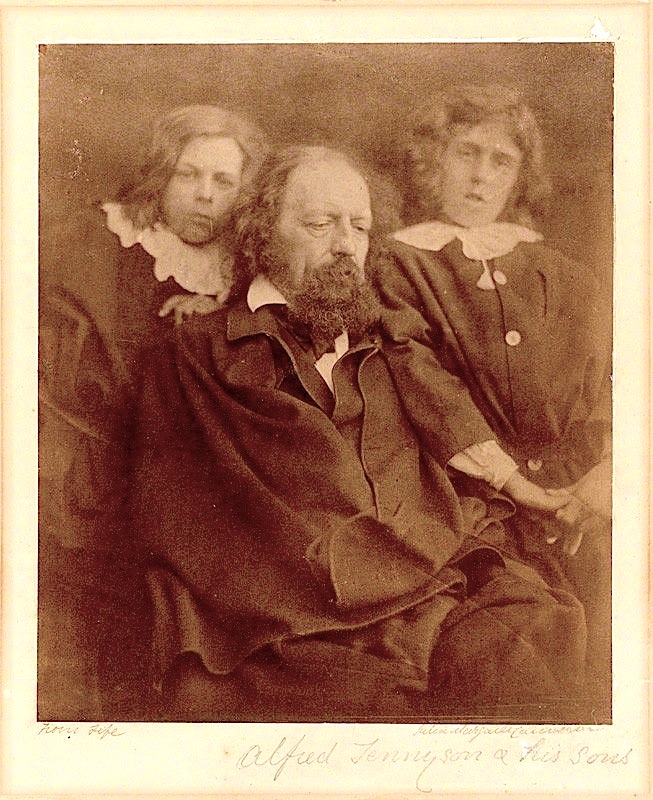

Tennyson and his sons, photographed by Julia Cameron, c.1865.

1865. June to September. For the extended holiday period Lewis Carroll's journal records no mention of the Isle of Wight or Tennyson. He spent the summer in London visiting and photographing families and children of friends such as the artists Arthur Hughes and James Sant. He also holidayed on the northeast coast, at Redcar and Whitby, close to his family and cousins. In November there appeared the reprinted first edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, now with "1866" on the title-page. This replaced the first printing which Lewis Carroll had scrapped, on the recommendation of his artist John Tenniel, because of the inferior printed quality of the illustrations. Some time after this reappearance Carroll returned to his journal's left-hand side blank pages, and at 12 October began to list "[Presentation Copies of Alice.]" These began with his child-friends: Alice Liddell, Princess Beatrice, Lorina Liddell, Edith Liddell ... Una Taylor (see 1864) — 38 names in all. At 30 October the author later inscribed adult recipients: [Party at Croft Rectory, Common Room Ch. Ch., A. Tennyson Esq. — 22 names.] The modern editor of Lewis Carroll's Diaries informs us that Tennyson's copy was inscribed "A. Tennyson and Mrs. Tennyson with the Author's kind regards. Dec. 1865." (Diaries, 5: 18n12, citing "76 names" of recipients currently known). Throughout all the 400 plus pages of Volume 5 of his published journal, spanning the period September 1864 to January 1868, this retrospective note on the presentation book-copy was Carroll's sole mention of Tennyson. Only the associated place name "Freshwater" had by then been allowed to assume a more frequent and public though cautiously disguised role in Carroll's later reminiscences. [See 1866, main chronology].

In the new children's storybook itself the situation was somewhat different. Whilst it should be remembered that the work of writing and shaping the book had been largely completed earlier, in happier times, Carroll was apparently still resolved to pass on his text, in this case with a discernible revenant of Tennyson. In his mournfully felt poem and extensive funeral dirge In Memoriam, A. H. H. [see Carroll-Tennyson Part I 1850] Tennyson had employed to good effect some of his hallmark romantic atmospheric imagery, as with "Or in the all-golden afternoon," Pt. LXXXVIII, v7. Carroll had already emulated this to lighten the tone of his own remembrance poem Solitude [1853], with lines on "the golden hours of Life's young spring…."(verses 9-10). Now, in the opening frame-poem to his inaugural children's fantasy dream tale of Alice there appears the celebrated Lewis Carroll hallmark phrase "All in the golden afternoon…," leaving the reader to ponder on how much of the associated romantic melancholy was derived from each of the now two crucial rifts in Carroll's recent life - those with Alice Liddell, and with Alfred Tennyson, each one then being longingly recalled and concealed by suitable disguises. It would seem plausible to suggest that the frame-poem would have come last from the author, and would have incorporated his later most decided and deliberate, albeit hidden, thoughts and feelings. Retrospective notes on the publication indicate that Carroll sent his "last portion marked 'Press'" on Tuesday 20 June 1865 (Diaries 5: 9, on a blank page for 13 September 1864), which could well have included such prefatory materials, with their joyous sunny blaze and tinge of lingering sadness.

Carroll also had a keen eye for approaching year-ends, and would often begin the theme of introducing his New Year's Resolutions as early as mid-December. A possible and significant deepening of this trend may be seen here, from 1864-1866, and may have reflected Carroll's concealed distress at - amongst other matters - the new and parlous state of his friendship with Tennyson. The following few entries examine this possibility, before returning to the main chronology:

1865. December. On Monday 18 and along the pattern of the previous year , Carroll wrote "O that with this dying year my evil life might die, and a new, holier life begin." At Sunday 31 his journal bears the citation "Eccl. ix.10" [Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might; for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave, whither thou goest. A. V.] It was a hard lesson, but his New Year prayer was then to have "grace to do His will 'with my might'" (Diaries 5: 124).

1866. December. Earlier than in the previous years, on Wednesday 5, Carroll entered the plea "May I leave behind, with the fast ending year, my old self." On Tuesday 11 he pleaded to be spared, to serve better, to be forgiven "all that is past… to put away my old life…." At Monday 31 his journal then carries two full paragraphs of self- recrimination: with the looking back on each passing year "with its wasted time ... follies and ... sins" he was growing "sadder every time." He then pleaded for "Pardon (for) the sins of the past year" and added a resounding "Oh take me home again, as a sheep that has long wandered from Thy fold…" (Diaries 5: 187, 190).

By the close of 1867 his pattern of pre-empting New Year's Resolutions appears to have returned to the less frequent one of 1864-65. It begins on Friday 20 December with "Oh Lord, as the years go by, draw me nearer and nearer to Thyself…." By Tuesday 31 he had returned to his family security at Croft and recorded "A year of great blessings and few trials…." His lament was "how feebly and ineffectually" he had striven to live "nearer to God." (Diaries 5: 376-8). If there had ever been a possibility of deeper personality malaise and social disruption it had now been resolved internally. Tennyson and the Isle of Wight were no longer to be resented, feared or avoided. Even the new story venture Alice's Adventures in Wonderland had by now become a definite best-seller, with publisher Macmillan seeking further print-runs of 3000 rather than a mere 1000 (3 September Diaries 5: 173). [ A fuller study of the prayers and private pleadings of Lewis Carroll is made elsewhere (Dyer, 2016: 374-380) for the period c.1860-c.1890].

1866. On Monday 9 April Carroll noted in his journal that he went and called upon a Mr. and Mrs. Boyes "whose acquaintance I made at Freshwater." (Diaries 5: 141). Again, however, no further mention of the brief Tennyson years on the Isle of Wight was felt necessary nor permitted. His long summer vacation period, as in 1865, was again passed in London, and on the northeast coast at Saltburn, Whitburn and Whitby.

1867. Much of this year Lewis Carroll spent in learning French for his trip to the Continent, and in travelling through France, Germany and Russia, whilst concentrating on religious edifices such as Cologne Cathedral, the various peoples of the countries, and as many photo shops as he could find. "The Russian Journal" (Diaries, 5: 255-369 ) covers the period Friday 12 July to Saturday 14 September, ending with a 2 a.m. moonlit Channel crossing of four hours from Calais to Dover, which Carroll passed wide awake and musing - perhaps on romantic poetry and the now revived Carroll-Tennyson Chronology, Part II moonlight effects of 1859 - in the prow of the boat. [See 1876 below for Carroll's subsequent and pronounced liking for rough sea trips].

1868. On Saturday 4 April Carroll was again in London, calling on the sculptors Alexander Munro and then later on James Westmacott to see what they were sending to the R. A. He also saw "a beautiful" piece entitled Elaine after Tennyson's tragic heroine, but "for some unknown reason" (Diaries 6: 14n8) Carroll strangely attributed it in error to Westmacott rather than to its actual sculptor Thomas Woolner.

The incident with the "beautiful "Elaine'" sculpture appears to reflect an apparently trivial confusion of facts, but provoked by a defensive mental reaction [here the repression by Carroll of hurtful memories of Tennyson, together with certain associated events]. This was quite typical of Lewis Carroll and indeed of people in general when subjected to stressful situations. Barely a year or two earlier, in October 1866 whilst struggling to advise his younger brother Wilfred Dodgson regarding the latter's determined efforts, of some few years already, to court and marry the young Alice Donkin who was still fifteen years of age, Carroll referred to "the very anxious subject" of "A. L.", instead of "A. D." The recent editor of Lewis Carroll's Diaries notes that "he probably meant to write "A. D.," but then allows the possibility that the discussion had involved Alice Liddell, or even "someone else with the same initials" (Diaries 5: 180 and n298). The negligible chance of such a dilution of Lewis Carroll's major involvement is however strongly suggested by an almost identical event the previous October. There Carroll had written Wilfred "a long letter on the subject of Alice Donkin ... and urged on him the wisdom of keeping away ... for a couple of years" (110). Further subsequent and defensive involvement of Lewis Carroll with Tennyson and Elaine is discussed below [see 1870].

Grave of Archdeacon and Mrs Dodgson in Croft churchyard, Collingwood 48.

1868. Carroll's father died suddenly and "in harness" on Sunday 21 June 1868. The grieving son's journal closed later that day and only recommenced on Sunday 2 August. Whilst securing the move of his sisters from Croft in North Yorkshire to Guildford in Surrey he had the pleasanter task of computing his profits from the sale of the first Alice book, which currently came to a total of £580 [conversion through 580 gold sovereigns to today's value gives approx. £190,000]. His journal pages for the month of December and New Year's Eve are then totally devoid of prayers, recriminations and devout resolutions. On Tuesday 22 December he had been in London visiting his friends: the actress Ellen Terry and family , the artistic Sants and others. His journal then closed with a curt "No further record for the year" (Diaries 6: 38, 50, 69). When we remove from consideration the Poet Laureate's official valedictions for deceased characters of national importance, substantial differences are seen to exist in the responses to deaths by Tennyson and Carroll, not least in their choices, as still budding young writers, of the significant persons to be eulogised in literary form: the one choosing his dearest male college friend, the other his dearest mother.

Ellen Terry, photographed by Carroll in 1865.

1869. On Friday 1 January, at Guildford with his sisters, Lewis Carroll's journal reopened with a brief "God bless the New Year to each and all of us!" Tennyson published The Holy Grail and Other Poems, and was already completing plans to avoid Isle of Wight sightseers with a new and more private summer home for his family, at Aldworth House, Black Down, overlooking the Sussex Downs and just south of Haslemere. Lewis Carroll published his Phantasmagoria, a collection of both nonsense verse and some other poems. A vibrant new element entered the life of Carroll in the form of the girl who would soon become his favourite and most successful child model for photography - Alexandra Rhoda Kitchin (b. 1864), daughter of Carroll's older Christ Church colleague George W. Kitchin. The girl was almost universally known by her family pet name of "Xie" (pronounced "She") [from "Alexa - Exa - X - diminutive Xie," or similar derivation].

One of Carroll's photographs of Xie Kitchin in early girlhood.

With his own family now based south of London near Guildford, Surrey, Lewis Carroll would also be tantalisingly close to the railway lines south from Guildford - Godalming - Haslemere - South Downs - and the completed new Tennyson house. However, what is more clearly evident is that from late September into October this year he spent "a week at Torquay with the Argles, which I enjoyed very much." (Diaries 6: 97). Canon Marsham Argles (1814-92) of Oxford and Peterborough, was well known to Lewis Carroll from frequent stops on railway journeys north. He had a large family including Agnes Beatrice Jane "Dolly" (1857-1944), known to Carroll as "my friend Dolly", and with whom he carried on a permitted correspondence through her eleventh and twelfth years [1868-69]. The Argles and Torquay may be identified as a recuperative element in the life of Lewis Carroll at this time, as also may the volume publication of his collected short poems, Phantasmagoria noted above.

1870. On March 3 whilst at Christ Church, and with some evident deliberation and fawning, Carroll finally wrote again to Tennyson. He had somewhere obtained a copy of a printed poem, The Window, which Tennyson had originally written for composer Arthur Sullivan in 1866, and which Sullivan had printed up in 1867. Carroll's purpose appears to have been to flatter the Poet Laureate with a request for permission to make the unpublished piece more widely known. Tennyson chose to reply via his wife's written hand, expressing annoyance at any such circulation of his unpublished works. Thereafter their exchanges became more heated and destructive of "any further friendship" (Cohen & Green, 1979, I: 150-151, 151-3, Letters of 7 & 31 March; n2 notes the incompleteness of the surviving correspondence). Carroll's seaside holidays later this year would be to an aunt at Hastings, then to Margate for five weeks with his sisters, with one early, tentative and exploratory trip to Eastbourne [see 1877].

In June 1870 came an obvious consolation for Carroll after the most recent disaster with Tennyson. Robert Cecil Marquis of Salisbury was inaugurated as the new Chancellor of Oxford University, with Carroll in the audience. Within a very short time Carroll was able to provide family photographs [now in albums at Hatfield House]; be on very good terms with Lady Salisbury and the four young children, James and William and Maud and Gwendolen, and from then on to receive regular invites to the Hatfield House Children's New Year's Day parties (Diaries 6: 118-121, 139). On Tuesday June 30, Carroll attended the Royal Academy (Diaries 6: 122, retrospective entry) where the exhibits included a striking painting of Tennyson's Elaine by the artist Sophie Anderson whose work Lewis Carroll already had on his Christ Church apartment wall. His omission (repression) of any mention of this Elaine was in stark opposition to his previous and delighted encounter with another [see 1868], and may perhaps be attributed to the recent return here of enduring and painful difficulties with his much sought idol Tennyson.

At this year's end Carroll thus found himself in sympathy with both of "the great French and Prussian nations" in their recent war, with no hint of any partisan return to the flag-waving heroics of Tennyson's youthful poetry of the earlier Crimean War [see Part I: 1855]. Carroll's fervent wish now was "May Peace come with the new year!" (Diaries 6: 138), and this obvious and beneficial hope for the world of politics may well have extended also to the unspoken hope for his own more personal and now once again devastated dealings with the yet again offended and socially elusive Laureate.

1871. This year of completion for Carroll's major project with his illustrator John Tenniel saw the second Alice book Through The Looking Glass arrive in Carroll's hand finally on Wednesday and Friday, 6-8 December. Earlier, in September, he had visited the artist Sir Noel Paton, at the Edinburgh studio (Paton away), and then to the artist's home on the Isle of Arran. This latter journey involved boat crossings, the first since Carroll's Continental Trip of 1867, and he found "The sail ... most agreeable." (Diaries 6: 179-183). It would be another two years before he adopted a regular annual routine with boat crossings, upon his return to the Isle of Wight. Then, he would come to employ sea crossings, and especially rough ones, as a kind of therapy which would secure his eventual release from any further "Tennyson melancholy" [see 1876]. Tennyson too had been drawn to the sea, as in his "Break, Break, Break" of Poems, II of 1842. All educated Victorians would know and could identify the image of England in the rousing lines from Shakespeare's Richard II: "this sceptered isle ... This precious stone set in the silver sea." In his own final farewell the Poet Laureate would symbolically return to the sea, no doubt closely watched, albeit from a distance, by an admiring Lewis Carroll [see the concluding part of this chronology, coming shortly].

Carroll's summer of 1871, after several visits to London friends and galleries, had indeed turned southwards, to the region where his younger brother Skeffington was now curate, and with only a short rail journey from Guildford to Hambledon-Witley and through Haslemere to the vicinity of Tennyson's new quiet place at Black Down, Sussex. On Friday 21 July, leaving Guildford for Witley by train with his sisters Caroline and Margaret, Carroll was met by Skeffington, and "walked with him to Hambledon ...and saw the church" (Diaries 6: 170). Carroll's youngest brother, Edwin, was also now enrolled at Chichester Theological College, at the end of another of the railway lines south, from Guildford-Godalming-Witley-Haslemere - then Midhurst-Chichester, or Petersfield-Portsmouth-Southsea and Isle of Wight. It is difficult to ignore this close geographical proximity with Tennyson's new summer residence, with railway lines and nostalgic views passing in the distance to both east and west for journeys south and north. There were also other significant events which Carroll had pre-planned for that year's end. In ordering special presentation copies of the new Alice book, Carroll had asked his publisher Macmillan to provide three copies in impressive morocco leather, one each for Alice Liddell, Florence Terry and Tennyson, this latter volume now at the Tennyson Research Centre, Lincoln, UK (Diaries 6: 190-1 and n296). The carefully crafted "peace offering" was in the event well received, as shown in Carroll's briefly renewed and cautious correspondence with Tennyson, then carried out alongside a parallel letter-exchange with mutual friends, as specified below.

These mutual friends of the Tennysons and of Carroll were Mr. and Mrs. G. G. Bradley, the former a head teacher at Marlborough School, Wiltshire, and first met by Carroll at Freshwater in 1864. As previous neighbours of the Tennysons the Bradleys had gone so far as to christen one of their daughters Emily Tennyson Bradley (b. 1862). Emily and some of her siblings were all met and admired by Carroll, as new photographic subjects, in March 1871 at Oxford where the father had become Master of University College (Diaries 6: 142n215). Carroll wrote to Mrs. Bradley on 22 December 1871, referring to his "peace offering" in the form of the impressive morocco-bound book, and to Tennyson's reply of "a note of thanks from himself." Carroll further admitted to being "quite pleased with the result of my experiment" (Cohen I: 174), which may well have indicated a high degree of careful pre-planning and persistence with regard to the Laureate.

1872. All might have gone well if only Carroll had taken more time and shown more consideration for Tennyson's wariness of being sought out. However, on Saturday 13 January he was again in London where at the Gaiety Theatre he saw the operetta Box and Cox with music by Arthur Sullivan (Diaries 6: 197), which he had seen before in 1867 and which appears to have played a part in the earlier contretemps with Tennyson over permissions [1870]. On June 5 Carroll was in Nottingham to attend a talk on the cure of stammering by the speech therapist Dr. Lewin (Diaries 6:215), then on 18 June and with incautious persistence was again writing to the Poet Laureate, with advice on where to find a speech therapist (for Tennyson's youngest son, Lionel). Tennyson's reply of 23 June was notably cool (Cohen, I: 178 and n1). Only a decade had passed since the all too brief Carroll-Tennyson amicable years, when Carroll had photographed his poetic idol in 1862, embellishing the mounted print with the words of the Laureate which he so much admired: "The poet in a golden clime was born/With golden stars above/Dower'd with the hate of hate, the scorn of scorn,/The love of love" (Cohen I: facing p.60).

Of interest here is the quite different and positive response which Carroll's socially indelicate attempts at being helpful could elicit. The same month as the latest Tennyson rebuttal he also received a more grateful letter from another doyen of literature, of similar age to Tennyson, Sir Henry Taylor also of the Freshwater years [1864], who began his reply with "It is very kind of you to think of my daughter's infirmity…" (Diaries 6: 218n343, Letter of 21 June 1872. MS Dodgson Family Collection). Carroll's summer vacation months were then spent largely between London and Guildford, with three weeks with his sisters in August at Bognor on the south coast, and a day each at Hastings and Brighton. On Monday 29 July he had again visited his curate brother Skeffington at Hambledon near Godalming (Diaries 6: 227), but apparently (and wisely) made no attempt to drop by the nearby Tennyson retreat at Black Down, just over the Surrey-Sussex border.

Return to the Isle of Wight. The Sandown Years, 1873-76

Central part of Sandown Station, which opened on 23 August 1864, and is on the way to Shanklin.

Perhaps knowing that Tennyson and any further possibility of painful encounters and conflicts were now relatively far away on the Sussex Downs during the summer months, Lewis Carroll was once more drawn to visit the Isle of Wight. On Tuesday 16 September 1873 his journal records that he "Visited Sandown, Shanklin, Ventnor and Bonchurch." Housed at Bonchurch were his London friends the family of artist Louis William Desanges. Carroll chose as his new base the King's Head Hotel at Sandown, on the eastern side of the Isle (Diaries 6: 295). On Wednesday 17 September he returned to Guildford and London affairs, then on the following Tuesday, 23, returned to Sandown with his elder sister Fanny. Next day they went by coach to Carisbrooke Castle in the centre of the Isle, then by rail to Cowes, then back to Ryde by "steamer" and finally to Sandown. Conspicuously absent from the varied itinerary is any mention of Freshwater and old Tennyson haunts. By Friday 26 Carroll accompanied Fanny back across the water to Portsmouth, and returned to the Isle with his youngest though adventurous sister, Henrietta Dodgson. On Monday 29 September, with Henrietta and others, he "Went round island", noting that it was "very rough on South Side." That would have included passing by Freshwater Bay with its view to Tennyson Down, though all go unmentioned. The theme of "rough water" would however come to attain a larger significance [see 1876].

Scenery near Tennyson Down, Freshwater.

It had been a slow and cautious return, drawn out over the previous few years. From the familiar coastal Hastings-St. Leonards of his aunt, Carroll had gradually worked his way westwards, successively visiting the Sussex coast and towns of Eastbourne, Brighton, Chichester and Bognor. On Monday 8 September 1873 he had left Guildford for Southsea, Portsmouth, revisiting the view (since 1864) across to the Isle of Wight. At Southsea he took a day's lodgings with a Mrs. Pares, almost his exact contemporary, who was known to him and may well have functioned as an informant for essential local gossip such as the movements of the Tennysons. Katherine Pares, married to magistrate John Pares, was based at Albury near Guildford, Carroll's family home when away from Christ Church. On Monday 15 September Carroll once more journeyed by rail from Guildford to Southsea, and then took the steamer across to Ryde on the Isle of Wight. From there he visited Sea-View near Nettlestone Point on the eastern landward side of the Isle. This was to the summer residence of his London friend, the dramatist Augustus William Dubourg (1830-1910), whose "pretty little daughter" Evelyn Sophia (b. 1861) had been an instant favourite with Carroll in 1869, and whom he photographed in 1873 and 1875 (Diaries 6: 86 and n129, 294-5). Only then in September 1873, a day later on the Tuesday noted above, and mantled by this carefully woven new social and personal protective garb, did he seriously choose his new base of Sandown which, it should be noted, is on the east side of the Isle and as far away as possible from Freshwater and Farringford in the west. Whether this reflected a new ambivalence in his attitude to all things linked to Tennyson, or whether his choice was based on his newer friendships, or even on the more mundane considerations of tourism, is hard to determine.

1874. Monday 22 June. At the King's Head Hotel, Sandown, Carroll noted "No journal kept for nearly three months," then promptly repaired the hiatus (Diaries 6: 332-342). He had been to Sandown as early as 19 June that year, with his younger Christ Church colleague Edward Francis Sampson (1848-1918), who was "out of health." Over the next few days Carroll was at Shanklin, where he knew that his actress friends the Terry family were staying, and later he attended "the Japanese entertainment" with a Mrs. Napier and her four children, known to him from the previous summer's visit. Lewis Carroll's long vacation months were thus once more beginning to show all the signs of the close and pleasurable control of affairs which his particular personality demanded. It is tempting, from the well-documented evidence available for his fluctuating movements in the periods, to suggest that his mercurial efforts, whether knowingly or subliminally, were designed to remedy his "Tennyson melancholy." Such a personal therapy would now be vigorously pursued, at a safe but moderate distance from the site of the original melancholy experiences associated with Tennyson in 1864. To that end, perhaps, he had also arranged for his sisters Caroline and Margaret to visit him - "I am treating [them] to a trip to Sandown" his journal noted - meeting them on Tuesday 23 June at Portsmouth (no doubt from the train, all arranged and meticulously paid for by him), and escorting them to Southsea, then over the water and on to Sandown. Next day they all went to Shanklin,then on Thursday 25 went to Ryde, walked over to Sea-View, drove to Brading and then "home by rail" by which he meant back to Sandown and their lodgings. Such use of the unguarded epithet "home" is quite revealing of his current mental state with regard to social interactions. Clearly he was effectively finding his long desired new "home" on the Isle of Wight. A further indication of his improved mental state is found in his journal entry for Saturday 27 June: "I have begun again drawing from life" (Diaries 6: 343). Whilst that had been an early and adolescent pastime for Carroll up to completing his B. A. at Oxford - as on his northeast England 1855 cliff walks - it had lapsed since then with his photographic studies. Now however on Tuesday 4 April 1871, after making life studies of five year old Beatrice Hatch and another child, he could note it as "a line of Art I began the other day with a picture of Mabel and Rose Price" (Diaries 6: 143).

1874. Tuesday 25 August - 10 October. Carroll again put up at the King's Head, Sandown, noting in his journal "as usual." From then until Saturday 10 October, his holidaying was confident and almost non-stop: on the 26 August he "had chats" with known families from 1873, and the same day went over to Ryde and Sea-View, meeting friends who were staying there. Next day he was in Shanklin at the Napiers, then spent most of Friday "lounging about, and chatting with various friends" (Diaries 6: 355). His Putney cousins came down from London on September 1 (doubtless no chance event); on the 7th he went to Ryde with Sampson and they "joined the steamer" for a voyage around the entire Isle. A notable absence in the reporting there is any mention of the projecting coastal point known for the famous Needles and Lighthouse, the Old Needles Battery, and Freshwater Bay with a view to Tennyson Down. In late September and early October Carroll was back and forth over the water, escorting various elderly relations, his cousins and others of his sisters, from Portsmouth, Southsea and so on to Sandown. By Thursday 8 October, in a party of twelve siblings, cousins, married friends and their children's governess, he went to Ventnor and Bonchurch for "A perfectly lovely day" (Diaries 6: 362).

In sharp contrast to Carroll's earlier troubled end of year and New Year's Eve musings, noted above for 1864-66, his typical year's end now was at Lord Salisbury's Hatfield House Children's Party and Ball, which he found "an exceedingly pretty sight." He stayed up to watch people dance the New Year in, partook of the second supper and then went "to the smoking room" with three other male guests. His journal throughout December records none of the earlier preoccupation with prayers and moral dilemmas, but does note the passing of "the year of 1874" with "one of those evenings at Hatfield House which I have always found so enjoyable" (Diaries 6: 375).

1875. On Wednesday 25 August Lewis Carroll travelled by railway from Guildford to Southsea, crossed the water to Sandown and put up at the York Hotel, smaller and further inland, but with the same proprietor, Mr. Bignell. The same day saw Carroll on the beach, where he met young Kitty Napier "and went back with her to call on the party" [see 1873]. The class of child entertained by Carroll would always have been accompanied by an unrecorded maid, nurse or ayah, the latter usually from India. The following day he did the same routine again with the children of two other known families (Diaries 6: 411).

A noticeable feature of Carroll's long vacations on the Isle of Wight during this brief period is the number of times he crosses the waters of the Solent and Spithead: in arriving, returning, arriving again; meeting and escorting friends and relatives, taking pleasure cruises - one could be forgiven for believing that he had formed a strong bond with the sea, and very likely as a revenant of his moonlit Calais to Dover crossing of 1867 on his return home from the Continent. Here in 1875 he was back in Guildford on 28 August; went to London and, unusually for him, took the steamer from Vauxhall Bridge to London Bridge on 6 September; then back on the Isle on Saturday 11 September. He crossed back to Southsea "for a trip" on the 17, which was repeated on Friday 1 October: "Went down to Guildford" again that Saturday, and back to Southsea-Sandown on Monday 4 October. By Wednesday 6 October Carroll with his friend Sampson and a mixed party went on "an expedition round the island", with plans to join the steamer at Ryde. When they reached Ryde Pier and found that "no steamer was going", the party "went instead to Cowes by boat." The very next day he and his party returned to Ryde and "took the steamer to Cowes" (Diaries : 413-424).

1876. Rough Waters. A peak of water crossings - a real life and parallel Carrollian crescendo, and with the intention, consciously or unconsciously sought, of resolving an impasse like that of Alice at the Red Queen's party - appears in Carroll's journal entries for the summer of 1876, and coincides with his finally leaving Sandown. Whilst no certain conclusions may be drawn in the absence of any further personal associations to the material, it remains credible that those two aspects of Carroll's life were intimately related. He always worked actively to shape his own life, with its own busy non-marital happiness and satisfactions, preferring to be his own physician, homeopathic herbalist, counsellor, guide and healer - opinionated in all things, and amassing a private and very comprehensive personal library of some three thousand volumes (Stern 1981), which included numerous medical and scientific books. In his own best known works he touched upon dreams, hopes and similar universal matters, which even Sigmund Freud had not yet arrived at publishing. Carroll's obituary writer, in Carroll's own favourite London weekly publication, would eventually declare him to have been "The wise interpreter of dreams" (Punch, 29 January, 1898, vol. CXIV: 39), pre-empting Freud by two years. Carroll's increasing employment of frequent (Channel) sea crossings, as meticulously detailed in his private journal, show him in his final Sandown summer repeatedly passing near the Black Down on north-south and south-north railways; repeatedly crossing the waters of the Channel-Solent accompanying friends and family, and engaging in other wider steamer voyages off the south coast. On Wednesday 9 August, having organised a group outing including crossing by water between Ryde and Cowes, he penned a revealing comment upon his younger sister Margaret's objection to returning by the same means: "the water part (which took 40 minutes) was the only part worth doing ... it [his sister's objection] was decidedly not tanti." Nevertheless they returned by rail (Diaries 6: 480).

1876. Thursday 7 September. By September an increased tempo may be detected as the crescendo approaches. On Thursday 7 September he first brought his oldest sister Fanny "across the water", and then "Escorted Elizabeth to Portsmouth." [Four passes over water in one day. Total now 16 for that summer].

1876. Tuesday 19 September. Escorted sisters Fanny and Mary "across to Portsmouth." Next day, Wednesday 20 September, with his Christ Church friend Sampson he went "round the island" in a boat named "Heatherbell." On Friday 29 September he escorted all his remaining family members over to Portsmouth for their return home, completing 21 passes over water with his own return to the Isle.

1876. Monday 2 October. Clearly now in his own solitary element, Carroll "Went across the water, chiefly because it was so rough." He witnessed the opening of the new line from Portsmouth to Portsea Pier, then "Came back in a screw [motorboat or launch], about the roughest passage I have ever had." (Diaries 6: 485). On Saturday 7 October he returned to Guildford [Twenty-fourth water passage and fourth known pass by "Tennyson Sussex" that summer].

A further indication of Carroll's continued and improving mental powers was his publication this year of the complex nonsense-mystery tale The Hunting of The Snark, with illustrations by his new artist Henry Holiday of Hampstead London, and who was a mutual friend of the Christ Church family of Xie Kitchin [see 1869].

Carroll's few years of summer holidays at Sandown may thus be seen as his own self-determined style of life therapy, necessary to finally overcome the melancholy disappointments of the rebuttals from Tennyson, albeit these being largely caused by Carroll himself from his own blind spots and inability to understand and sympathise more deeply with Tennyson's particular defensive needs. The sea, with its proverbial powers and cleansing action, both physical and spiritual, practical and symbolic, seems to have come to play a decisive part in that. Rough crossings, of bearable short duration, real and symbolic, were then - but briefly - at the forefront of Carroll's itinerary and deeper needs. His understanding of contemporary medicine and illness would have extended to the importance attached to concepts such as "crisis" and "climax", as in Victorian fever management, and his final Sandown weeks, as detailed here, bear surprising parallels to such treatments. His facility disguise, substitutions and concealment may have led him to encounter a viable substitute for the more ancient and primitive though still well known religious practice of scourging by flagellation, which he had initially attempted in symbolic form via his more fervent and anguished prayers (Dyer, 2016, Ch. 14 and n6, 374-380). Sandown had then provided regular sea crossings, and occasional more vigorous rough crossings, which appear to have then come to briefly occupy in Carroll's private life and journal the place previously reserved for his soul-wringing prayers and end of year resolutions.

Sandown would henceforward [1877] be replaced by Eastbourne and a much enhanced and welcomed conviviality. He would return briefly to Sandown with his colleague and friend Sampson for the final week-end of June 1881, and then again, travelling alone, for the last week-end of March 1883. As will be noted in a concluding part of this Carroll-Tennyson Chronology, the ailing Poet Laureate would also in his last months and years finally return to a long-standing involvement with affairs of the sea and of the human soul. These too Lewis Carroll would have absorbed, in part from Tennyson, his lifelong idolised poet-bard and sometime mentor.

Links to related materials

- Carroll-Tennyson Chronology, Part One: The Overtures, 1832-1857

- Carroll-Tennyson Chronology, Part Two: The Amicable Years, 1858-1864

- Carroll-Tennyson Chronology, Part Four: A Watershed and Acceptance, 1877-1889

- Carroll-Tennyson Chronology, Part Five: Final Glances, 1889-1898

- An Alfred Lord Tennyson Chronology

Bibliography

Carroll, Lewis. Lewis Carroll's Diaries. The Private Journals of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. Ed. Edward Wakeling. Vols. 5, 6 & 7. England: Lewis Carroll Society, 1999, 2001, 2003.

Cohen, M. N. and Green, R. L. The Letters of Lewis Carroll. 2 vols. London: Macmillan, 1979.

Dyer, Ray. Lady Muriel. The Victorian Romance by Lewis Carroll. Annotated Scholar's Edition. Leicester: Troubador, 2016.

Stern, Jeffery. Lewis Carroll's Library. Carroll Studies No. 5. Lewis Carroll Society of North America, 1981.

Additional reading

Buckley, J. H. Tennyson. Harvard University Press, 1960.

Gwynne, Stephen. Tennyson. A Critical Study. London: Blackie & Son, 1899.

Henderson, P. Tennyson. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978.

Hutchings, Richard J. Alfred and Emily Tennyson: A Marriage of True Minds. Newport: Isle of Wight County Press, 1994.

Nicolson, Harold. Tennyson: Aspects of His Life and Poetry. Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1923.

Tennyson, Charles. Aldworth: Summer Home of Alfred Lord Tennyson. Lincoln U. K.: Tennyson Research Centre, 1977.

Tennyson, Hallam. Tennyson: A Memoir. 2 vols. London: Macmillan, 1897.

Thwaite, Ann. Emily Tennyson: The Poet's Wife. London: Faber & Faber, 1997.

Truss, Lynne. Tennyson and His Circle (National Portrait Gallery Companions). London: National Portrait Gallery Publications, 1999.

Created 2 August 2022