he Dudley Gallery held its first General Exhibition of Water Colour Drawings in April 1865 at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly. Its founder’s committee of twenty-six members included artists such as Edward Poynter, Simeon Solomon, and Henry Moore, as well as influential critics like Tom Taylor and collector/connoisseurs. The two initial objectives of the gallery were the establishment of a venue exclusively devoted to drawings, as distinguished from oil paintings, and which should not, in its use by exhibitors, involve membership of a society such as the Old or New Water Colour Societies. These two conditions were not at that time fulfilled by any London exhibition, and the Dudley Gallery was not intended in any way to rival existing venues. In 1867 exhibitions of cabinet Pictures in oil were added as well, with these shows being held later in the year.

Green Summer. by Edward Burne-Jones, 1864. Watercolour and gouache on paper, 11 ⅜ x 18 ¼ inches (29 x 48.3 cm). Exhibited Old Water Colour Society, 1865, no. 105. Private collection. Click on image to enlarge it.

The establishment of the Dudley Gallery was called for due to the requirements of very many artists, and particularly young artists, for a gallery with liberal exhibiton policies in which they could display their work. Many of these artists would never have had their works accepted for exhibition at the Royal Academy, which tended to focus on oil paintings, while the exhibitions of the Water Colour Societies were open only to their members. The Dudley Gallery therefore had no regular membership and was open to both professional and amateur artists. It served as a means of establishing the reputation of many new artists who might otherwise never have come to recognition. A critic for The Art Journal, who recognized the galleries importance, pointed out in 1870: "The strength of the Dudley Gallery has been that it represents not one party, but many parties, that it asserts equal rights for all artists, whether recognized or unrecognized, simply on the basis of individual merit" while still acknowledging that "in the Dudley Gallery, from its first year, originality, genius, eccentricity, have found fair play and favour" (372). The gallery was an instant success, and it continued in this format until 1883, when it came under new management and became the Dudley Gallery Art Society.

The Enchanted Boat by Walter Crane, 1868. Pencil, watercolour, gouache and gum arabic on paper, 97/8 x 21 inches (25.1 x 53.3 cm). Private collection.

Exhibitions at the Dudley Gallery tended to be very heterogenous in nature, but it was the work of artists associated with the early Aesthetic Movement that gave the Dudley Gallery its particular character and notoriety. The Dudley Gallery quickly became the principal forum for the younger generation of artists associated with the nascent Aesthetic Movement, and it would remain the principal vanguard for this expression of advanced artistic taste until the opening of the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877. Works in the characteristic l’art pour l’art (Art for Art’s Sake) Dudley style rejected sentiment and morality as subjects and did not attempt to tell a story. These artists were more interested in the love of beauty. Even when some narrative content was retained the emphasis was primarily on achieving a harmonious arrangement of forms, colours, and tones with the decorative effect of the work being predominant.

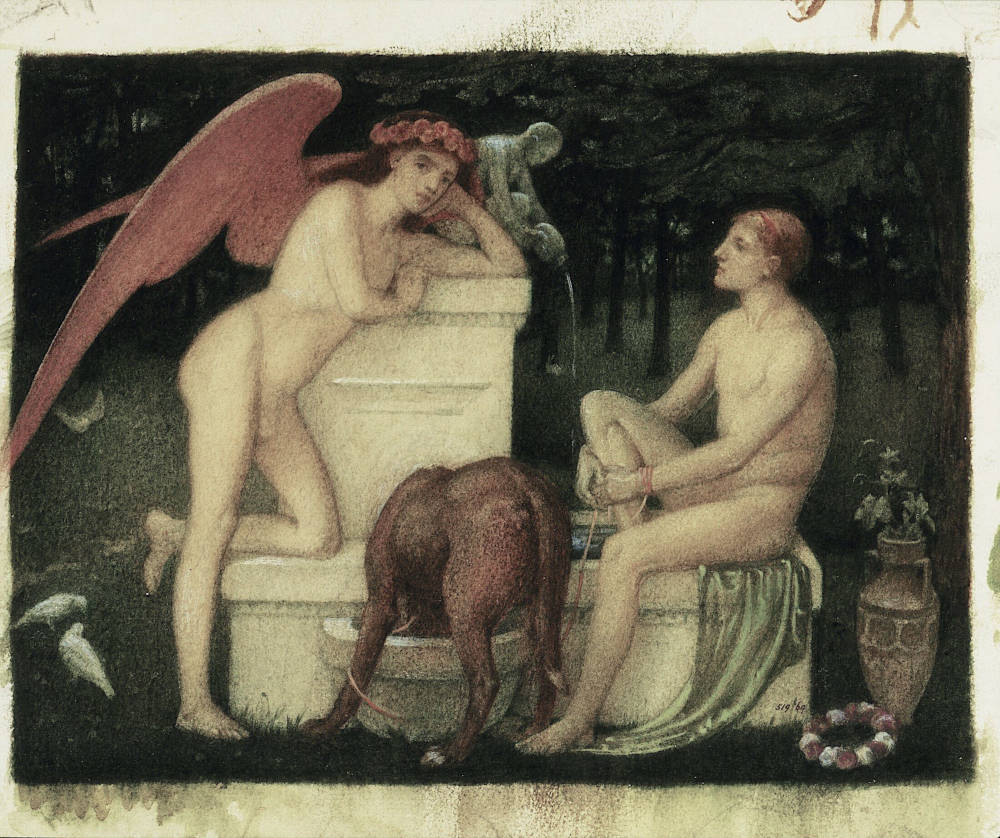

Reading of Love, He Being By by Robert Bateman, 1873. Watercolour and gouache on paper, 10 x 131/2 inches (25.4 x 34.3 cm). Signed and dated R.B./73, lower right. Private collection.

Hostile critics dubbed the more characteristic exhibitors in the Dudley style the "Poetry Without Grammar School." This term commenting on the beauty of the works, while lamenting their obvious technical shortcomings, was first used by a reviewer for The Westminster Review in 1869:

These are examples of a school in which the separability of the two parts of artistic culture, the knowledge of its grammatical elements and the susceptibility to its emotional charms, is most convincingly displayed; a school which produces pictures delightful for sentiment, but ridiculous for drawing; a school so incomplete, and, if appearances may be trusted, so contented with its incompleteness, that there really does not seem much to hope for from it in future. A picture needs to be drawn just as much as a poem needs to rhyme and scan; and it seems to us just as undesirable to exhibit these undrawn and formless suggestions of pictures as it would be to print the promising but puerile efforts of a poet of twelve. This we feel bound to put strongly, because our own want of grammatical training in art, our own keen enjoyment of the fancy, the sentiment, the sense of colour, of landscape, of poetry, shown in these works, would naturally render us lenient to their particular shortcomings. But it cannot be too much urged that if this school is ever to make any mark, it must cease to be a poetry-without-grammar school; such work as it produces at present must be regarded as mere fancies, hints, sketches, possibilities of pictures, by the suppression of which, until a foundation of fact and accuracy comes to sustain the superstructure of sentiment and beauty, the public would lose little, and the artists probably gain much. [594]

Some Have Entertained Angels Unaware by Edward Clifford, 1871. Pencil, watercolour, gouache and gum arabic on paper, 25 x 38 inches (63.8 x 96.7 cm). Signed and dated Edward Clifford 1871, lower right. Private collection.

Although the Dudley Gallery’s most characteristic exhibitors are therefore generally referred to today as the "Poetry Without Grammar School", contemporary critics had also labelled this group of painters "the legendary," "the archaic," "the loathly school," or the "mystico-mediaeval or romantico-classic" group (Lambourne, Aesthetic Movement, 93).

Based on Walter Crane’s Reminiscences the “Poetry Without Grammar School” is most often considered to consist of a group centered around its leader Robert Bateman and to consist of Crane, Edward Clifford, Harry Ellis Wooldridge, Alfred Sacheverell Coke, Edward Henry Fahey, and Theodore Blake Wirgman (84-85). This group was united in its admiration for the works Edward Burne-Jones was exhibiting at the Old Water Colour Society. In his Reminiscences Crane recalled seeing Burne-Jones' work for the first time at the exhibition of the Old Water-Colour Society in 1865:

The curtain had been lifted, and we had a glimpse into a magic world of romance and pictured poetry, peopled with ghosts of 'ladies dead and lovely knights,' - a twilight world of dark mysterious woodlands, haunted streams, meads of deep green starred with burning flowers, veiled in a dim and mystic light, and stained with low-toned crimson and gold, as if indeed one had gazed through the glass of 'Magic casements opening on the foam / Of perilous seas in faerylands forlorn.' It was, perhaps, not to be wondered at that, fired with such visions, certain young students should desire to explore further for themselves [84]

Critics, however, were unimpressed by Burne-Jones’ influence on this group of neophyte artists. In 1870 a reviewer from The Art Journal discussing Burne-Jones' watercolours stated: "Mr. Burne Jones in the Old Water-Colour Society stands alone: he has in this room no followers; in order to judge how degenerate this style may become in the hands of disciples, it is needful to take a walk to the Dudley Gallery" (173). While Crane freely admits the influence of Burne-Jones on this group he clearly fails to acknowledge the important influence of Simeon Solomon, one of the star exhibitors at the Dudley Gallery. Solomon is known to have been friendly with this group, particularly its leader Robert Bateman, whose home he visted at Biddulph Old Hall in Staffordshire. By the time Crane came to write his Reminiscences, however, the ever respectable Crane would not have wanted to be seen to have been closely associated with a man who had been largely dropped from polite society after being convicted of homosexual offences in 1873.

Right: Eros and Ganymede by A. S. Coke, 1869. Watercolour and gouache on paper, 8 x 101/2 inches (20.3 X 26.7 cm). Collection of Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Left: Heliogabalus, High Priest of the Sun by Simeon Solomon, 1866. Pencil, watercolour, gouache and gum arabic on paper, 183/4 x 113/8 inches (47.6 x 28.9 cm). Signed with SS monorgram and dated 1866, lower right. Private collection. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In looking at contemporary reviews of the Dudley Gallery exhibitions it is obvious that critics considered other artists to be associated with the Poetry Without Grammar School, based on their exhibits, in addition to those listed by Crane. The reviewer for The Westminster Review, for instance, acknowledged this as such in 1869 when he also mentioned such artists as Helen Thornycroft, Alyce Thornycroft, Lucy Madox Brown, Marie Spartali, Andrew Benjamin Donaldson, and Simeon Solomon to fall within this group. Other artists could easily be included such as Thomas Armstrong, Catherine and Oliver Madox Brown, William De Morgan, Alfred Hassam, George Howard, Edward Robert Hughes, and John Roddam Spencer Stanhope.

Sunset on the Coast. Henry Moore. Oil on canvas, 8.25 x 18 inches; labelled verso. Exhibited: Exhibition of Pictures by the Moore Family, Corporation Art Gallery, York, 1912. Courtesy of the Maas Gallery. Click on image to enlarge it.

In 1870 a critic for The Saturday Review accused works in the Dudley Gallery winter exhibition of “alarming eccentricity” and “prejudiced, partial, one-sided view of nature”:

This exhibition sustains its character for interesting variety and alarming eccentricity…This Gallery contains a choice company of artists who take a somewhat prejudiced, partial, one-sided view of nature; it is a stronghold of Messrs. Solomon, Donaldson, Stanhope, Crane, Armstrong, Barclay, and others, who dread nature as they eschew what is commonplace, who present to the world as a pledge of genius inveterate mannerism… Why will these people cling so affectionately to ugliness, when nature on all sides teaches that the supreme worship in art should be beauty?” [594]

That same year a critic for The Illustrated London News similarly complained about their "eccentric idiosyncrasies" and "the erratic attempts at mediaeval mimicry or pseudo-classicality in contributions by Messrs. Donaldson, Solomon, Stanhope, Crane and others" (478). Some critics, however, praised the merits of these artists and found the beauty in their pictures as well as pointing out their obvious faults. For example, the reviewer of the 1870 The Art Journal claimed that, despite their faults, these “proverbially peculiar” artists provided a necessary response to “the meanest naturalism” found in contenporary art:

These Dudley people are proverbially peculiar. Thus it would be hard to find anywhere talent associated with greater eccentricity than in the clever, yet abnormal, creations of Walter Crane, Robert Bateman, and Simeon Solomon...Such a style may be set down as an anachronism; yet, beset as we are by the meanest naturalism, we hail with delight a manner which, though by many deemed mistaken, carries the mind into the regions of the imagination...Though not wholly satisfactory, we hail with gladness the advent of an Art which reverts to historic associations, and carries the mind back to olden styles when painting was [the] twin sister of poetry" (87).

The work of this group of avant-garde artists exhibiting at the Dudley Gallery was influenced by the major painters associated with the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism and Aesthetic Classicism, the fusion of which led to the Aesthetic Movement. The art of the Poetry Without Grammar School was also much more influenced by early Renaissance painting than the early work of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Many of these young artists had actually travelled to Italy and seen the work of the Italian primatives first hand. No early work by members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood would ever have been mistaken for a painting by an artist before the time of Raphael but this was not so with this younger group of painters. In 1869 a reviewer for The Spectator noted: "As for the clique of painters who, leaving nature, apply themselves to the imitation of old pictures, it is useless to criticize them. Such imitation leads to nothing good. It is a dead thing quite incapable of progress, and one can only regret that artists with such a gift for colour as Mr. S. Solomon and Miss Spartali should have set themselves a task that must necessarily be barren of good results. If, indeed, they would really follow in ancient steps they must learn the elements of drawing" (322). Even landscape painting at the Dudley Gallery tended to be treated in an ornamental fashion by these progressive artists, as compared to the hard-edged realism that characterized the treatment of landscape painting during the first phase of Pre-Raphaelitism. In 1871 the critic of The Saturday Review noted that "mediaevalism in the Dudley Gallery permeates even landscape art. There is a way of painting nature as if she had grown very old; opposed to this is the ordinary method of making nature appear new and young, as if she had sprung into life but yesterday" (177). This decorative treatment of landscape may also have been derived from the work of Burne-Jones.

Bibliography

“Art, Dudley Gallery.” The Westminster Review. 91 (April 1869): 593-97.

Crane, Walter. An Artist’s Reminiscences. London: Methuen & Co., 1907.

“Dudley Gallery. Fourth Winter Exhibition.” The Art Journal. 9 (1870): 372-73.

“Dudley Gallery. Sixth General Exhibition of Drawings.” The Art Journal. 9 (1870): 86-88.

“The Dudley Gallery.“ The Saturday Review. 30 (November 5, 1870): 594-95.

“The Dudley Gallery of Water-Colour Drawings.” The Saturday Review. 31 (February 11, 1871): 177-78.

“The General Exhibition of Water Colours.” The Spectator. 42 (March 13, 1869): 322-324.

Lambourne, Lionel. The Aesthetic Movement. London: Phaidon, 1996.

Lanigan, Dennis T. ”The Dudley Gallery 1865-1882: The Principal Forum for the Early Aestheic Movement.” The Review of the Pre-Raphaelite Society. 10 (Spring 2002): 18-25.

Lanigan, Dennis T. “The Dudley Gallery Water Colour Drawings Exhibitions 1865-1882.” Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies. 12 (Spring 2003): 74-96.

“Society of Painters in Water-Colours. Sixty-Sixth Exhibition.” The Art Journal. 9 (1870): 173-175,

“Winter Exhibition of Oil Paintings at the Dudley Gallery.” The Illustrated London News. 57 (November 5, 1870): 478-79.

Last modified 29 May 2022