eorge Eliot knew from the start what her literary portraiture would not be. It would not, for example, be Lord Rupert Conway, the handsome young prime minister of England in Rank and Beauty, or the Young Baroness (1856):

eorge Eliot knew from the start what her literary portraiture would not be. It would not, for example, be Lord Rupert Conway, the handsome young prime minister of England in Rank and Beauty, or the Young Baroness (1856):

The door opened again, and Lord Rupert Conway entered. Evelyn gave one glance. It was enough; she was not disappointed. It seemed as if a picture on which she had long gazed was suddenly instinct with life, and had stepped from its frame before her. His tall figure, the distinguished simplicity of his air it was a living Vandyke, a cavalier, one of his noble cavalier ancestors, or one to whom her fancy had always likened him, who long of yore had, with an Umfraville, fought the Paynim far beyond the sea. Was this reality?

"Very little like it," responded the author of "Silly Novels by Lady Novelists" (Essays, pp. 307-08). A portrait like this was to George Eliot what a portrait by Sir Sloshua was to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848: lifeless convention masking as truth, hollow cliché evoking a stereotyped response. To avoid slosh, the Pre-Raphaelites maintained, one must paint from new pictorial models and from the direct observation of nature. By the same token, George Eliot wanted her literary portraits to present fresh perspectives and real knowledge of character rather than occasions for effusive sentiment. [44/45]

In pursuing that aim, her portraiture passed through three major phases. In Scenes of Clerical Life and Adam Bede, she was primarily concerned to show that looks do mirror personality, that there are, as G. H. Lewes put it in "The Novels of Jane Austen," "subtle connections between physical and mental organisation" (p. 106). In these early works, phrenology helped her to create portraits that give reliable clues to temperament and behavior. With Romola and Felix Holt, however, the correlation between appearance and reality becomes more problematic. Influenced less by phrenology and more by Ruskin and Hawthorne, Eliot grew preoccupied with the portrayal of evil and with the discrepancy between innocent-looking portraits and corrupt sitters. Finally, the gap between static picture and changing person becomes normative in Eliot's portraiture, so that Middlemarch and Daniel Deronda abound with partial portraits, visual definitions of character that are qualified as soon as given. The knowledge afforded by portraiture grows more uncertain and more complex as Eliot's work progresses, and the significance of the English portrait tradition itself becomes ambiguous. Sometimes the tradition represents an admirable continuity of English history, but at other times it reflects only the vanity of an exclusive and dying aristocracy. The variety of meanings it can encompass, from the moral and psychological to the historical and sociological, makes Eliot's literary portraiture richer than that of any earlier novelist in English.

How to depict a nonentity sympathetically is the first task George Eliot set herself. The traditional rhetorical functions of the character sketch — laus et vituperatio — do not apply to Amos Barton.2 He cannot be celebrated because he is not a hero, yet he cannot be caricatured because he is our fellow man. George Eliot solves the problem by turning her first literary portrait into a nonportrait:

Look at him as he winds through the little churchyard! The silver light that falls aslant on church and tomb, enables you to see his slim black figure, made all the slimmer by tight pantaloons, as it flits past the pale grave-stones . . . as Mr Barton hangs up his hat in the passage, you see that a narrow face of no particular complexion — even the small-pox that has attacked it seems to have been of a mongrel, indefinite kind — with features [45/46] of no particular shape, and an eye of no particular expression, is surmounted by a slope of baldness gently rising from brow to crown. [2:23]

The model for this description is the silhouette, with its lack of internal definition and its reversal of the customary tonal values of figure and ground in portraiture. Amos Barton is defined by negation: a fleeting black shadow in a night-time setting where the chiaroscuro highlights not the protagonist but the monitory emblems of death surrounding him — the tombs and "pale gravestones" which foreshadow his loss of Milly. His physiognomy is likewise that of a nonentity; it has "no particular" humor, structure, or expression. An individual without individuality, he has no hair, and his sloping forehead suggests to the phrenological eye a deficiency of intellectual faculties. Even his smallpox scars, themselves negations of the man, leave no distinctive disfigurement. His silhouette is colorless, as he is, and its form is constricted by angular, diminishing lines: a slim figure that grows slimmer below the waist, a narrow face, a sloping forehead, seen by slanting moonlight. Such a reversal of traditional portrait values would, in an eighteenth-century context, almost certainly be satiric; but here it implies no disapproval.4 It simply introduces a nobody.

As Gombrich and Piper point out, silhouettes and physiognomy were associated in the treatises of Johann Caspar Lavater, where the standard form of illustration was the profile silhouette drawn from life. If Amos's portrait descends from such sources, it is a reminder that many of George Eliot's descriptions have a rich background in the pseudo-scientific systems of expressive anatomy that influenced the arts for more than two centuries before she began to write. From the French neoclassical discourses on l'expression des passions to Lavater's physiognomy to the phrenology of Gall and Spurzheim, empirical observers had attempted to interpret the mind through the language of the body.6 The common assumption of their endeavors was clearly articulated by Sir Charles Bell in 1806:

Anatomy stands related to the arts of design, as the grammar of that language in which they address us. The expression, attitudes, and movements of the human figure, are the characters which is adapted to convey the effect [46/47] of historical narration, as well as to show the working of human passion, and give the most striking and lively indications of intellectual power and energy."(pp. vi-vii)

The same linguistic metaphor was used by George Eliot's favorite phrenologist, George Combe, when he spoke of "the natural language of the faculties," meaning, of course, those thirty-three faculties of the brain whose development phrenologists could interpret from the shape of the cranium.8 Combe's treatise on Phrenology Applied to Painting and Sculpture (1855) taught artists how to mold heads that are phrenologically compatible with the characters and passions represented in any work of art.

George Eliot was acquainted with Combe through their mutual friend, Charles Bray, who had become an enthusiastic student of phrenology in the 1830s (Haight, p. 37). Bray took Marian Evans to London to have a phrenological cast of her head made in 1844, and he introduced her to Combe in 1851 (Haight, pp. 51, 100-01). Marian and Combe were both associated with the Westminster Review after she moved to London (Haight, pp. 109, 123-24), and their friendship lasted until her elopement with Lewes in 1854 (Haight, p. 166). Although she did not subscribe to every article of Combe's scientific creed, she nevertheless reiterated her belief in the general principles of phrenology in a letter to Bray of 1855: "I am not conscious of falling off from the 'physiological basis.' I never believed more profoundly than I do now that character is based on organization. I never had a higher appreciation than I have now of the services which phrenology has rendered towards the science of man" (Letters, II, 210).

As George Eliot's letter suggests, the basic premise of Gall's system is that mind has a physiological basis. Character is determined not by intangible, divinely implanted spirit but by the physiological organization of the brain and central nervous system. The mind is composed of more than thirty independent faculties localized in different regions or organs of the brain, developed in proportion to the growth of those organs, and mirrored in the size and shape of the cranium. The faculties fall into three general groups, each group predominating in one part of the head. The intellectual faculties center in the brow and forehead, or anterior lobe; the moral and religious faculties, in the top of the head, or coronal region; the [47/48] selfish and animal faculties, in the occiput, or posterior lobe. The temperament of any individual will depend upon the balance of his propensities; thus George Eliot was a little worried that her moral aptitudes might not be strong enough to check her animal propensities (Letters, 1, 167). Finally, phrenology postulated four major character types-the nervous, the bilious, the sanguine, and the lymphatic, which were holdovers from the older psychology of the humors.9

The truth and utility of this system were self-evident to many creators of literary character in the mid-nineteenth century. Poe and Whitman both drew heavily upon phrenology, as did two English writers whom George Eliot respected: Bulwer-Lytton and Charlotte Brontë.10 In Eliot's own work, the vocabulary of phrenology is most explicit in Scenes of Clerical Life (1857) and Adam Bede (1859). Not all of the portraits in these early stories are phrenological, but a good many are. In the first chapter of "Janet's Repentance," for example, we meet Lawyer Dempster.

Mr Dempster habitually held his chin tucked in, and his head hanging forward, weighed down, perhaps, by a preponderant occiput and a bulging forehead, between which his closely clipped coronal surface lay like a flat and new-mown table-land. [1:4142]

As Maurice L. Johnson observed in 1911, Dempster is described in this passage as an "animal-intellectual temperament," wanting in moral faculties (561) His preponderant occiput indicates a massive development of the selfish faculties such as love of approbation and self-esteem, and of the animal faculties such as combativeness, destructiveness, and amativeness (sexual passion). Dempster's bulging forehead is a sign of his great intelligence, but his flat coronal surface suggests a deficiency of the moral and religious faculties such as benevolence, veneration, and conscientiousness. As Johnson points out, Dempster's character and conduct in the story "correspond strikingly with his phrenological portrait" (Johnson) The lawyer turns out to be intelligent, unscrupulous, and sadistic. — For other phrenological portraits in Scenes of Clerical Life, see "Amos Barton" (3:48, 3:56) and "Mr Gilfil's Love-Story" (2:153, 5:209).

A vivid contrast to Dempster is found in the double portrait that [48/49] opens Adam Bede. In Seth Bede we see a very full development of the coronal region:

Seth's broad shoulders have a slight stoop; his eyes are grey; his eyebrows have less prominence and more repose than his brother's; and his glance, instead of being keen, is confiding and benignant. He has thrown off his paper cap, and you see that his hair is not thick and straight, like Adam's, but thin and wavy, allowing you to discern the exact contour of a coronal arch that predominates very decidedly over the brow. [1:5]

If Dempster's coronal surface was "like a flat and new-mown tableland," Seth's is like an "arch"; and the fact that it predominates over his brow suggests that his moral faculties, unlike Dempster's, are more highly developed than his intellectual capacities. Combe could have been listing Seth Bede's virtues when he said that "to represent strong Benevolence, Veneration, Hope, Conscientiousness, and Firmness, the top of the head, or coronal region, must be drawn high and arched" (40). In Seth's fully structured portrait, George Eliot fills in the spaces that she left blank in Amos Barton's silhouette: figure, coloring, expression of the eye, and physiognomy.

Adam Bede's portrait provides another sort of contrast to Seth's. First we hear Adam's voice singing a hymn; then we see the singer:

Such a voice could only come from a broad chest, and the broad chest belonged to a large-boned muscular man nearly six feet high, with a back so flat and a head so well poised that when he drew himself up to take a more distant survey of his work, he had the air of a soldier standing at ease. The sleeve rolled up above the elbow showed an arm that was likely to win the prize for feats of strength; yet the long supple hand, with its broad finger-tips, looked ready for works of skill. In his tall stalwartness Adam Bede was a Saxon, and justified his name; but the jetblack hair, made the more noticeable by its contrast with the light paper cap, and the keen glance of the dark eyes that shone from under strongly marked, prominent and mobile eyebrows, indicated a mixture of Celtic blood. The face was large [49/50] and roughly hewn, and when in repose had no other beauty than such as belongs to an expression of good-humoured honest intelligence. [1:4-5]

A phrenologically sophisticated Victorian reader would immediately have recognized in Adarn the bilious temperament, with an admixture of nervous traits. The bilious character was defined by the American phrenologist, Orson S. Fowler, as a type "in which the muscles predominate in activity, characterized by an athletic form, strong bones and sinews, black hair and eyes, dark skin, strong and steady pulse, hardness, force, and power" (quoted Davies, Phrenology, p. l81).

The bilious character is what the older humor psychology called the choleric: a temperament given to wrath and violence. In other words, Adam's shortness of temper and propensity to fisticuffs are foreshadowed in his introductory portrait. But his biliousness is balanced and held in check by his alertness and intelligence, which are qualities of the so-called nervous temperament, in whom mental activity is strong. What Adam would be without this fortunate development of his intellectual faculties may be seen in the contrast between him and his mother: "There is the same type of frame and the same keen activity of temperament in mother and son, but it was not from her that Adam got his well-filled brow and his expression of large-hearted intelligence" (4:55).

Whether Adam's intelligence came from his father we do not know, for we never see that hard-drinking carpenter in life. But the other major character who is destined to become part of the Bede family — Dinah Morris — does receive a careful phrenological portrait early in the novel, when she is preparing to preach on Hayslope Green. The portrait has more in common with Seth's than with Adam's:

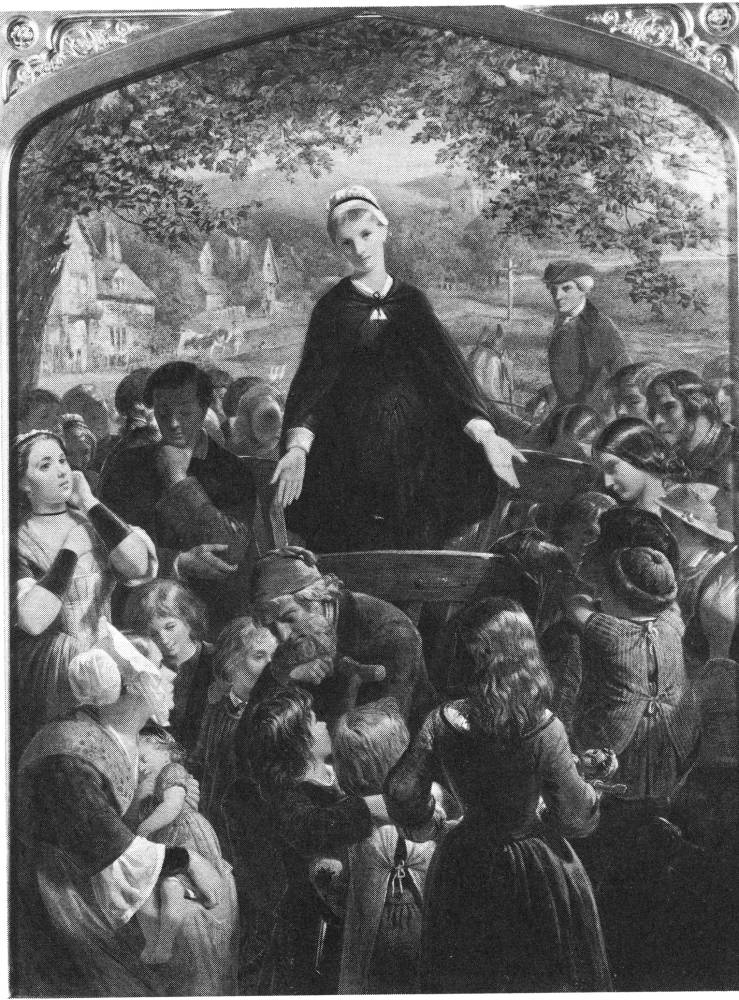

There was no keenness in the [grey] eyes; they seemed rather to be shedding love than making observations; they had the liquid look which tells that the mind is full of what it has to give out, rather than impressed by external objects. She stood with her left hand towards the descending sun, and leafy boughs screened her from its rays; but in this sober light the delicate colouring of her face seemed to gather a calm vividness, like flowers at [50/51] evening. It was a small oval face, of a uniform transparent whiteness, with an egg-like line of cheek and chin, a full but firm mouth, a delicate nostril, and a low perpendicular brow, surmounted by a rising arch of parting between smooth locks of pale reddish hair. The hair was drawn straight back behind the ears, and covered, except for an inch or two, above the brow, by a net Quaker cap. The eyebrows, of the same colour as the hair, were perfectly horizontal and firmly pencilled; the eyelashes, though no darker, were long and abundant; nothing was left blurred or unfinished. [2:29-30]

E. H. Corbould, Dinah Morris Preaching on Hayslope Green Figure 25 in print version. Click upon thumbnail for a larger image.

Nothing, certainly, is left blurred or unfinished in this description, which Queen Victoria liked so well that she commissioned a watercolor to be painted of it for her private collection. As with Seth, to whom Dinah is a sort of phrenological sister, the moral and religious faculties are more highly developed than the intellectual capacities. Dinah's forehead is low, and the faculties of observation, which are situated near the eyes, do not have the keenness of Adam's. But the "rising arch" above her brow implies a full growth of the coronal organs of benevolence and veneration (capacity for religious devotion). Their coronal arches, then, reveal the most characteristic propensities of the two gentle Methodists. The nonphrenological associations of Dinah with leaves and flowers complement the corporal language of her portrait.

The technical vocabulary of phrenology becomes increasingly rare in George Eliot's fiction after Adam Bede. Felix Holt has "large veneration" and "large Ideality" (5:98), but he is alone among Eliot's later heroes and heroines in receiving so explicit a diagnosis. Although she continued to believe in the existence of what Lewes had called "subtle connections between physical and mental organisation." Eliot lost faith in craniology or organology as a reliable interpreter of those connections. A letter of 1870 to Dante Gabriel Rossetti articulates the diffidence of her maturity:

One is always liable to mistake prejudices for sufficient inductions, about types of head and face, as well as about all other things. I have some impressions — perhaps only prejudices dependent on the narrowness of my experience — about forms of [51/52] eye pages missing [53/54] of male desire which has little to do with the real nature of women; as the passage unfolds, the voice of the male narrator takes on the clubby accents of a literate amorist recalling a particularly irresistible milkmaid. A later description of shows how even a physiognomical portrait like those of Adam, Seth, and Dinah can be falsified by male egoism:

Every man under such circumstances is conscious of being a great physiognomist. Nature, he knows, has a language of her own, which she uses with strict veracity, and he considers himself an adept in the language. Nature has written out his bride's character for him in those exquisite lines of cheek and lip and chin, in those eyelids delicate as petals, in those long lashes curled like the stamen of a flower, in the dark liquid depths of those wonderful eyes. How she will doat on her children! (15:228).

"Every man" here includes both Adam and Arthur Donnithorne, who thinks that Hetty has "the most charming phiz imaginable" (9:149). But in Hetty's case the "great physiognomist" is misled by his dream of gratification. The delicate flower-mother is actually capable of infanticide when brought to it by a man acting on a sentimental fantasy of women like this one. It takes Mrs. Poyser's "feminine eye" to detect "the moral deficiencies hidden under the 'dear deceit' of [Hetty's] beauty" (15:232).

Another pictorial deceit that pervades the courtship of Hetty and Arthur takes the form of an Ovidian mythological-pastoral motif. This favorite theme of Renaissance painters is nearly always a sign of false idealization and egoism in George Eliot's literary portraits. Arthur says that Hetty is "a perfect Hebe, and if I were an artist, I would paint her" (9:149); whereas Hetty dreams of Arthur as a Poseidon and herself as a Tyro (13:202). Allusions to the golden age and the pastoral ideal of a locus amoenus embellish their trysts (12:192-94, 13:204, 15:228), but the motif takes an ironic turn later in the novel when Hetty, wandering lost and pregnant, is visualized as Medusa — specifically as the Medusa Rondanini at Munich (37:145; for these two different images, see Pastoral Novel, pp. 60-67; Wiesenfarth, George Eliot's Mythmaking, pp. 43-44). Ovidian idealization in George Eliot's work is usually associated with characters who pursue a paradise of individual pleasure in a morally strenuous postlapsarian world. This pagan motif, which reappears in Romola and Daniel Deronda, is the antithesis of the Christian idealization that will be examined in the next chapter of this study. [54/55]

The human potential for egoism and evil raises both philosophical and aesthetic questions for portraiture. Gall identified "Murder" as one of the basic human faculties, but his more melioristic followers dropped it from the phrenological scheme (Davies, p. 8). Ruskin, in the second volume of Modern Painters (1846), struggled to reconcile ideal portraiture with the "immediate and present operation of the Adamite curse." In order to show both good and evil, Ruskin concluded, the artist must supplement empirical physiognomy with spiritual intuition:

the pursuit of idealism in humanity . . . can be successful only when followed through the most constant, patient, and humble rendering of actual models, accompanied with that earnest mental as well as ocular study of each, which can interpret all that is written upon it, disentangle the hieroglyphics of its sacred history, rend the veil of the bodily temple and rightly measure the relations of good and evil contending within it for mastery. [Works, 4.184, 187]

Here Ruskin's diction moves from the dispassionate language of science to the fervent cadences of Christianity. The passage epitomizes his whole approach to nature and art, which characteristically proceeds through empirical observation to religious vision. The agency of this insight Ruskin identifies a few chapters later as the penetrative imagination, a moral and aesthetic faculty not included on most phrenological charts. Like Ruskin, George Eliot was interested in a portraiture that would reveal moral struggle and change; for although she had abandoned the Evangelical dogma of an Adamite curse, she continued to believe in the phenomenal reality of good and evil.

A new mode of portraiture came to hand in Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Marble Faun (1860), a seminal work in the history of literary pictorialism by virtue of its influence upon both the later Eliot and Henry James. George Eliot mentioned The Marble Faun in the same letter from Italy that announced the conception of Romola to her publisher, and she no doubt included Hawthorne's romance of contemporary Rome in the preparatory reading for her own romance of historical Florence ( Letters, III, 300; see Dahl). Hawthorne taught George Eliot how to use ecphrasis, or the verbal imitation of works of visual art, as a technique of psychological revelation and prophecy. The characters in The Marble Faun pass from innocence to experience [55/56] through the knowledge and commission of evil. As Donatello, Miriam, and Hilda psychically reenact the fall of Adam, they gain and lose symbolic physical resemblances to various works of art placed within the story to represent different stages of their moral transformation. The most important of these correlatives are the Faun of Praxiteles, the so-called Portrait of Beatrice Cenci by Guido Reni, The Archangel Michael by the same painter, and a bust of Donatello modeled by the sculptor, Kenyon.22

This technique of characterization caught George Eliot's imagination. She had created similar effects on a minor scale in her early work, but after reading The Marble Faun she began to amplify her ecphrases. In Romola and her later novels, she regularly juxtaposes her characters with morally significant art works located inside the story. As in Hawthorne, these art works are sometimes "real" (that is, imitated from known originals) and sometimes purely fictive.

The most important pictures in Romola are fictive studies of Tito Melema and the heroine by Piero di Cosimo. Piero depicts his subjects together, separately, and with third persons, often in mythological roles that bear upon their situations in the story. Knowledge of character is the primary aim of the series, which begins early in the novel when Piero and Nello the barber debate whether Tito's fair countenance is better suited for a history painting of "Sinon deceiving old Priam" or a heroic picture of Bacchus, Apollo, or St. Sebastian. When Nello says that Tito would "make a Saint Sebastian. that will draw troops of devout women" (4:63), George Eliot is probably thinking of the copy of Guido Reni's Saint Sebastian in the Dulwich College Gallery, which she saw on 9 May 1859 and judged "no exception to the usual 'petty prettiness' of Guido's conceptions" (Cross, II, 88).

The question, as with Hetty Sorrel, is whether physiognomy is a reliable index of character. Nello says that he cannot 'look at such an outside as that without taking it as the sign of a lovable nature" (4:66); but Piero argues that good looks may signify hypocrisy: "A perfect traitor should have a face which vice can write no marks on — lips that will lie with a dimpled smile — eyes of such agate-like brightness and depth that no infamy can dull them — cheeks that will rise from a murder and not look haggard" (4:63). Piero disavows any real knowledge of Tito's character at this first meeting, but his intuition is prophetic: Tito will betray virtually every major character in the novel.

The discussion in the barbershop establishes the frame of reference for Tito's subsequent portraiture. The young model favors Nello's vision of a Greek god, as we see when he commissions a wedding [55/56] portrait of himself and Romola in the roles of Bacchus and Ariadne. In this portrait Bacchus dispels the cares of Ariadne and crowns her in a marriage ceremony attended by Cupids "shooting with roses at the points of their arrows" (18:283). The lovers are seated on a ship covered with grapevines, ivy, and flowers. Leopards and tigers surround the happy pair, while dolphins sport nearby in the waves. The entire scene is "encircled by a flowery border, like a bower of paradise" (37:56). The painting is a false pastoral fancy portrait of the sort that Arthur and Hetty like to imagine for themselves in Adam Bede.

Tito interprets the details of the picture to Romola as

pretty symbols of our life together — the ship on the calm sea, and the ivy that never withers, and those Loves that have left off wounding us and shower soft petals that are like our kisses; and the leopards and tigers, they are the troubles of your life that are all quelled now; and the strange sea-monsters with their merry eyes — let us see — they are the dull passages in the heavy books, which have begun to be amusing since we have sat by each other" (20:306).

This interpretation perfectly expresses Tito's hedonistic code, which seeks to achieve pleasure and power and to avoid pain. Like Hawthorne's latter-day faun, Tito-Bacchus brings pagan and epicurean values into a Christian world that has learned a deeper moral truth.24 His mythological portrait is painted on a cabinet designed to hide and replace a crucifix which Tito finds unpleasant, and his distaste for the Christian art of Florence reflects his distaste for the Christian ideas of self-denial, sin, death, and judgment (3:49). From the same aversion, he misreads Piero di Cosimo's historical allegory of the triumph of Christianity, interpreting its central figure as a symbol of the Golden Age or "the wise philosophy of Epicurus." Tito's taste in art exemplifies the worldly and sensuous response which Ruskin called "aesthesis," but shows no signs of the higher religious faculty which Ruskin's Modern Painters II called "theoria" (4.42-50). Aesthesis is the "mere sensual perception of the outward qualities and necessary effects of bodies," whereas theoria is "the exulting, reverent, and grateful perception" of beauty as a creation and gift of God.

At first Romola accepts the portrait of Bacchus and Ariadne as a true image of her marriage. Like Nello, she is highly susceptible to the physiognomy of surface appearances. Romola is first attracted to Savonarola by the physiognomy of his hands and face (15:240). Eliot's description of Savonarola's face is modeled upon Fra Bartolommeo's famous portrait in the Accademia at Florence (Letters, III, 295). But later she comes to see the picture as a "pitiable mockery" (37:56). It would seem even more hollow if she knew its literary sources. The portrait conflates [57/58] two Bacchic episodes from Ovid's Metamorphoses. The god's marriage to Ariadne occurs in Book 8, and was a favorite topos of Renaissance painters. But Tito transfers the nuptials to a scene in Book 3 in which Bacchus is threatened with enslavement by the crew of a ship that is carrying him, disguised as a boy, to Ariadne on Naxos.29 In retribution for their ill-treatment, Bacchus manifests his divinity, turns the crew into dolphins, stops the ship in midocean, and covers it with vines and cats. What Tito really commissions, then, is a picture of himself triumphant over slavers at sea, with Romola inserted as the final prize of the voyage. This choice of texts is appropriate yet deeply ironic, for although Tito had the good luck to escape from pirates at sea, his fortunes in Florence are based upon his refusal to ransom his captured foster-father, Baldassarre, from Turkish slavery. Its Ovidian sources, then, hint at the dark truth which the pastoral portrait conceals.

Although the picture of Bacchus and Ariadne is painted by Piero di Cosimo, it is entirely Tito's conception. Piero's own vision of the couple is antithetical to that of his young patron. Whereas Tito appreciates an illusion of harmonious sensuous surfaces, Piero di Cosimo possesses the more disturbing faculty which Ruskin named the penetrative imagination. According to Ruskin, this power works "by intuition and intensity of gaze," and perceives "a more essential truth than is seen at the surface of things." It has insight not only into nature but also into human character: "it looks not in the eyes, it judges not by the voice, it describes not by outward features, all that it affirms, judges or describes it affirms from within . . . it is forever looking under masks and burning up mists; no fairness of form, no majesty of seeming will satisfy it" (Ruskin, 4, 251, 285).

George Eliot's Piero incarnates Ruskin's conception of the penetrative imagination. Piero is a tireless seer whose sole intervention in the plot — the cutting of Baldassarre's bonds — symbolizes the artist's role as a liberator of truth.31 Piero's aesthetic, with its combination of empirical observation and spiritual intuition, and its steady recognition of death and the grotesque, is thoroughly Ruskinian.32 George Eliot chose Piero for her novel not only because his dates fit and his vita is one of the most colorful in Vasari, but also because his works were so little known to her audience that she could freely invent an oeuvre for him to serve her own expressive purposes.33 [58/59]

While he executes Tito's commission for the picture of Bacchus and Ariadne, Piero paints the same sitters in two portraits that express his deeper insight. He represents Romola in the role of Antigone with her blind father at Colonos, as if to suggest that Romola has not really been exalted beyond tragedy by her Bacchus. Piero also paints Tito in a scene which calls the triumph of Bacchus into question:

Piero turned the sketch, and held it towards Tito's eyes. He saw himself with his right hand uplifted, holding a wine-cup, in the attitude of triumphant joy, but with his face turned away from the cup with an expression of such intense fear in the dilated eyes and pallid lips, that he felt a cold stream through his veins, as if he were being thrown into sympathy with his imaged self.

"You are beginning to look like it already," said Piero, with a short laugh, moving the picture away again. "He's seeing a ghost-that fine young man. I shall finish it some day, when I've settled what sort of ghost is the most terrible — whether it should look solid, like a dead man come to life, or half transparent, like a mist." [18:286]

The Bacchic celebrant in this picture has been surprised by his own worst fear. He exhibits the standard facial expression prescribed for the passion of terror in physiognomical treatises, but his corporal attitude belongs to the opposite emotion of "triumphant joy." This expressive paradox may be glossed by a passage from the last volume of Modern Painters (1860): "Evil had been fronted by the Greek, and thrust out of his path. Once conquered, if he thought of it more, it was involuntarily, as we remember a painful dream, yet with a secret dread that the dream might return and continue for ever" (7.283).

Wiesenfarth (p.155) argues persuasively that the corporal attitude of Piero's reveler is modeled upon Michelangelo's Bacchus, which was-on display at Florence in George Eliot's time. Piero's portrait of Tito depicts the Greek's secret dread of the return of repressed evil. Barbara Hardy has noted that Gwendolen Harleth experiences a similar moment of obscure terror when dressed in a Greek costume for the tableau of Hermione in Daniel Deronda (pp. 176-77). The motif of the fearful Greek also figures in The Marble Faun, where Donatello has a panic fear of ghosts and memento mori; and it appears earlier in Romola, when Tito and the heroine, immediately after viewing their Ovidian portrait, are frightened by Piero di Cosimo's allegorical procession of the triumph [59/60] of time. As Ruskin reminded his readers, "Florentine art was essentially Christian, ascetic, expectant of a better world, and antagonistic, therefore, to the Greek temper" (7.279)

Hawthorne would have called Piero's portrait of Tito a "prophetic picture," after one of the Twice-Told Tales in which a young couple gradually take on the expressions of worry and madness brought out in their wedding portraits by an intuitive painter. The Marble Faun contains several such pictures, and Piero's portrait of Tito fits the pattern because it foretells Tito's fearful and guilty recognition of Baldassarre on the steps of the Duomo. In prophetic pictures, the artist paints the reality he sees behind the veil of appearances. When that reality later manifests itself to others, nature seems to imitate his art.

Prophetic pictures therefore lend a primitive and magical quality to literary pictorialism.38 They seem to be painted by wizards, to have souls of their own, and to exercise an occult control over their models. The convention belongs ultimately to the Gothic romance, and finds its classic Victorian avatar in Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray. Curtis Dahl has called attention to the parallels between Basil Hallward's sin-laden portrait of Dorian and Piero di Cosimo's portrait of Tito as a fear-filled phiz; see Dahl, p 92, and Richards, p. 303. If Romola anticipates fin de siècle aestheticism, it does so in its use of prophetic pictures and its representation of Tito Melema's hedonistic temperament.40 This is not to say, of course, that George Eliot abandoned rationalism for mysticism when she shifted from phrenological to prophetic portraiture. As the Gothic novelist may in the end provide natural explanations for apparently supernatural effects, so George Eliot attributed Piero's powers of prophecy to a secular faculty of imagination. Her interest in prevision and second sight remained firmly empirical (see Preyer).

George Eliot did not employ prophetic pictures again until Daniel Deronda, but in the novel that followed Romola she developed the ironic portraiture she had used in Tito's picture of Bacchus and Ariadne. The discrepancy between innocent image and fallen nature is especially prominent in the representation of Mrs. Transome in Felix Holt. For more than thirty years, Mrs. Transome has lived with the secret that her second son, Harold, was conceived in an [60/61] adulterous liaison with Matthew Jermyn, a domineering lawyer. Her unhappiness has marred her youthful beauty almost more than time itself, so that there is a touching contrast between her appearance at the time of the story (1832-33) and an earlier portrait of her that hangs in the smaller drawing-room at Transome Court: "It was a charming little room in its refurbished condition: it had two pretty inlaid cabinets, great china vases with contents that sent forth odours of paradise, groups of flowers in oval frames on the walls, and Mrs Transome's own portrait in the evening costume of 1800, with a garden in the background" (42:236).

The paradisal odors, floral groups, and garden background make it clear that this is an Edenic portrait of Mrs. Transome before her fall. The imagery recalls Tito's picture of Bacchus and Ariadne. But the sad history of the sitter is visually recapitulated by the apparition of the present Mrs. Transome: "as if by some sorcery, the brilliant smiling young woman above the mantelpiece seemed to be appearing at the doorway withered and frosted by many winters, and with lips and eyes from which the smile had departed" (42:237). This is a contrast not only between summer and winter, but also between innocence and experience. Mr. Jermyn is in the room at the time.

Another ironic portrait in Felix Holt is that of Harold Transome the illegitimate son. It hangs in the same room as his mother's, "a picture of a youthful face which bore a strong resemblance to her own: a beardless but masculine face, with rich brown hair hanging low on the forehead, and undulating beside each cheek down to the loose white cravat" (1:17). Mrs. Transome contemplates this portrait at the beginning of the novel, as she awaits Harold's return after an absence of fifteen years. Although she reminds herself that he will be altered from the boy she remembers, she is emotionally unprepared to find, when he finally arrives, that "her son was a stranger to her" (1:24). Portraiture in Felix Holt is continually belied by the changing reality of its subjects.42

George Eliot suffered enough disappointment from portraits in her life to grow wary of them in her art. "Poor Marian never did like any representations of herself," according to Margharita Laski (p. 75) The photograph that J. J. E. Mayall made of Eliot in 1858 so appalled her that she determined never to be photographed again (Letters, III, 307-08. For Eliot's view of photography, see also Letters, III, 449;VI, 385;VII, 213, 233.). Thereafter she sat for only two portraits: one by Samuel Laurence in 1860 and one by Frederic Burton in 1864-65. She expressed her most characteristic misgivings about portraiture in 1879, when the question of a commemorative effigy for G. H. Lewes arose:

Any portrait or bust of Him that others considered good I should be glad to have placed in any public institution. But for myself I would rather have neither portrait nor bust. My inward representation even of comparatively indifferent faces is so vivid as to make portraits of them unsatisfactory to me. And I am bitterly repenting now that I was led into buying Mayall's enlarged copy of the photograph you mention. It is smoothed down and altered, and each time I look at it I feel its unlikeness more. Himself as he was is what I see inwardly, and I am afraid of outward images lest they should corrupt the inward. [Letters, VII, 233] .

Here George Eliot expresses her residual Puritan distrust of graven images of the Worshipped One. Portraits of those dear to her often made her feel deceived and somehow violated.

Will Ladislaw reacts in much the same way to Adolf Naumann's proposed portrait of Dorothea in Middlemarch The young German artist is inspired by the sight of Dorothea standing near the statue of Ariadne in the Vatican Museum. The scene, which owes a great deal to the opening chapter of The Marble Faun, raises some important questions about vision and definition in portraiture. How can Dorothea be perceived and represented in her full reality? Naumann offers a number of alternative portrait schemes, but Ladislaw objects vigorously to all of them, and his resistance cannot be entirely attributed to jealousy. The next chapter will discuss his Ruskinian criticism of Naumann's religious-aesthetic idealizing; but here Will's Lessingite objections to portraiture as such must be considered, for such objections underlie and complicate many of the character-descriptions in George Eliot's last two novels.

Will's reasoning applies not so much to Naumann's work in particular as to any visual representation of a living human being. In a speech already quoted, Will argues that painting and sculpture [62/63] cannot represent women because "they change from moment to moment," and the visual arts cannot capture the "movement and tone" of such change (19:292). The novel bears Will out on this point; the very next chapter emphasizes the discrepancy between what Naumann saw and what Dorothea was at the same moment experiencing: a painful change in her conceptions of her husband and her own role in marriage. Ultimately Dorothea eludes the many pictorial analogies which attempt to characterize her throughout the novel. Character, as Mr. Farebrother later says in his famous paraphrase of the Laokoön, "is not cut in marble — it is not something solid and unalterable. It is something living and changing . . ." (72:310). George Eliot made the same point in a letter she wrote to Sara Hennell while working on Middlemarch: "One must not be unreasonable about portraits. How can a thing which is always the same, be an adequate representation of a living being who is always varying?" (Letters, V, 97). And in Daniel Deronda the narrator interrupts a description of Gwendolen with the following Lessingite observation: "Sir Joshua would have been glad to take her portrait; and he would have had an easier task than the historian at least in this, that he would not have had to represent the truth of change — only to give stability to one beautiful moment" (I1 :170). The beautiful moment is worth capturing, but it cannot tell all that is worth knowing about a person.

Gwendolen's portraiture is elusive not only because she changes but also because she pictures herself more actively than does any previous George Eliot character. Gwendolen sees Miss Harleth in a charmingly varied sequence of paintings and tableaux vivants. Every time we are invited to admire her in a picturesque attitude, our response is qualified by our peripheral awareness that she has calculated the visual effect and admires it too:

There was a general falling into ranks to give her space that she might advance conspicuously to receive the gold star from the hands of Lady Brackenshaw; and the perfect movement of her fine form was certainly a pleasant thing to behold in the clear afternoon light when the shadows were long and still. She was [63/64] the central object of that pretty picture, and every one present must gaze at her. That was enough: she herself was determined to see nobody in particular.... [10:156]

Gwendolen's continuous aesthetic consciousness of herself usurps the narrator's. The literary portraiture is internalized by the character, and thus becomes a technique of psychological as well as of physical representation. Gwendolen's similar habit of imagining herself the heroine of a play is discussed by Brian Swann. The next chapter will examine several of Gwendolen's self-portraits in greater detail.

If Gwendolen imagines other people as anything more than her appreciative audience, she usually sees them as caricatures. She has a lively satirical turn of mind which is at once engaging and slightly heartless. Early in the novel, Rex Gascoigne, while following the hunt at Gwendolen's instigation, falls from his father's horse, Primrose, and suffers a painfully dislocated shoulder which is reset by a stray blacksmith. When news of the accident is brought to Gwendolen, she affects concern but soon begins to visualize the scene in terms of a comical sporting print: "Now Rex is safe, it is so droll to fancy the figure he and Primrose would cut-in a lane all by themselves — only a blacksmith running up. It would make a capital caricature of 'Following the hounds"' (7:110).

Gwendolen's knack for caricature extends to unknown persons, such as the Mr. Grandcourt who is about to take up residence in the neighborhood. "Why, what kind of man do you imagine him to be, Gwendolen?" her mother asks. "Let me see!" replies the young observer of men and manners:

Short — just above my shoulder — trying to make himself tall by turning up his mustache and keeping his beard long — a glass in his right eye to give him an air of distinction — a strong opinion about his waistcoat, but uncertain and trimming about the weather, on which he will try to draw me out. He will stare at me all the while and the glass in his eye will cause him to make horrible faces, especially when he smiles in a flattering way. I shall cast down my eyes in consequence, and he will perceive that I am not indifferent to his attentions. I shall dream that night that I am looking at the extraordinary face of a magnified insect — and the next morning he will make an offer of his hand. [9:138-39] [64/65]

This sketch is amusing, but its prophecies are shaped more by dramatic irony than by penetrative imagination. Caricature, because it wilfully distorts its subjects, tells even less about them than portraiture normally does. When she meets Mr. Grandcourt, Gwendolen is surprised to find that he "could hardly have been more unlike all her imaginary portraits of him." George Eliot's description is at once detailed and impatient:

He was slightly taller than herself, and their eyes seemed to be on a level; there was not the faintest smile on his face as he looked at her, not a trace of self-consciousness or anxiety in his bearing; when he raised his hat he showed an extensive baldness surrounded with a mere fringe of reddish-blond hair, but he also showed a perfect hand; the line of feature from brow to chin undisguised by beard was decidedly handsome, with only moderate departures from the perpendicular, and the slight whisker too was perpendicular. It was not possible for a human aspect to be freer from grimace or solicitous wrigglings; also it was perhaps not possible for a breathing man wide awake to look less animated.... His complexion had a faded fairness resembling that of an actress when bare of the artificial white and red; his long narrow grey eyes expressed nothing but indifference. Attempts at description are stupid: who can all at once describe a human being? even when he is presented to us we only begin that knowledge of his appearance which must be completed by innumerable impressions under different circumstances. We recognize the alphabet; we are not sure of the language. [11:161-62]

Attempts at description may be stupid, but the narrator of Daniel Deronda goes right on making them, even enlisting the venerable comparison of physiognomy with a language. In this case, the language consists of many negatives. Grandcourt has no smile, no self-consciousness, no anxiety, no hair, no beard, no grimace, no wrigglings, no animation, no expression in his neutrally colored eyes, a complexion that is no longer fair, and features that do not depart very far from a norm. These negations recall the portrait of Amos Barton, but the strategy of presentation has a different significance here. We are not meeting a nonentity. The absences in Mr. [65/66] Grandcourt's portrait are dictated by the traditional definition of evil as the absence of good.

Grandcourt's soul is dead to the good. He is evil in this traditional Christian and Shakespearean sense of the term, and he is the only character so conceived in all of George Eliot. The discrepancy between appearance and reality in his case is signaled by no ironic images of a lost pastoral paradise, because, unlike Hetty or Tito or Mrs. Transome, Grandcourt has never known innocence and has no desire to regain it. He does not change, and his appearance defies physiognomical interpretation. Only a terrifying normalcy conceals the death of his soul.

George Eliot's portraiture therefore emphasizes a perfect conventionality which lacks animation, a visual effect of death-in-life. In one description, for example, we see Grandcourt by firelight, lounging in his easy-chair with an after-dinner cigar:

The chair of red-brown velvet brocade was a becoming background for his pale-tinted well-cut features and exquisite long hand: omitting the cigar, you might have imagined him a portrait by Moroni, who would have rendered wonderfully the impenetrable gaze and air of distinction; and a portrait by that great master would have been quite as lively a companion as Grandcourt was disposed to be. (28:60).

Here Grandcourt has not only the inexpressiveness of a Moroni portrait but also the inhuman stasis of any portrait. The limitations of painting to which Lessing called attention are, for once, perfectly suited to the subject.

In the end a true portrait of Grandcourt emerges when he becomes identified with the prophetic picture of the dead face on the concealed panel at Offendene. This melodramatic nightmare-image terrifies Gwendolen early in the novel, and haunts her later in conjunction with her last glimpse of Grandcourt drowning in the Mediterranean: "a dead face — I shall never get away from it" (56:220). The picture of the corpse is to Grandcourt precisely what Piero's picture of the frightened reveller is to Tito Melema: an accurate revelation of the character's true though hidden nature.

Many of George Eliot's character-sketches are explicitly related to the great tradition of English portraiture that lasted from the Tudor era until around 1830. Shortly after Gwendolen has married [66/67] Grandcourt, for example, she is described as a "Vandyke duchess of a beauty" (45:21). The portrait thus evoked aptly symbolizes her social aspirations toward the aristocracy. Because the English portrait tradition was inseparable in George Eliot's mind from the heritage and class of those it depicts, it brings a historical and sociological dimension to her literary pictorialism.

Eliot knew the English school of portraiture well, having since childhood seen examples of it in private houses such as Arbury Hall and in public displays such as the National Portrait Gallery and the National Portrait Exhibition. The National Portrait Gallery opened in 1857, and its secretary, George Scharf, was a friend of the Lewes family. George Eliot met him early in 1862 and visited the gallery on her spring tour of the exhibitions in that year (Letters, IV, 13, 37). After attending the National Portrait Exhibition in 1867 she told Sara Hennell how worthwhile it was "to see the English of past generations in their habit as they lived — especially when Gainsborough and Sir Joshua are the painters."(Haight, p. 221, and Laski, pl. 56)

But Eliot's reaction to English portraiture was usually more ambivalent. On the one hand, she loved it and mourned the vanished pre-Victorian England which it represented. On the other hand, she often seemed in its portraits to flaunt the vanity, affectation, and unlimited privilege of the pre-Reform aristocracy. Her mixed feelings of nostalgia and alienation are reflected in her literary pictorialism, where the English portrait tradition sometimes provides access to the past and a welcome continuity between past and present, but at other times symbolizes an inaccessible and dying elite whom the younger and less aristocratic characters cannot and should not imitate.

The characteristic strategy of George Eliot's early historical fiction, as many critics have noted, is to abolish temporal distance by converting it into aesthetic distance. The narrative composes itself into a picture, and then draws the reader through the frame as if through a time barrier. Literary portraits serve this function in "Mr Gilfil's Love-Story," the most painterly of the Scenes of Clerical Life. The story begins in Mr. Gilfil's old age, but soon leaves the nineteenth century and flashes back to "the evening of the 21st of June 1788" (2:149). The transition is accomplished not only by fiat of the narrator but also by means of "two miniatures in oval frames" that hang in a closed-off room of the vicar's house. These depict Mr. Gilfil himself as a young man and Caterina Sarti as a girl of [67/68] about eighteen, "with small features, thin cheeks, a pale southern-looking complexion, and large dark eyes." She has "her dark hair gathered away from her face, and a little cap, with a cherry-coloured bow, set on the top of her head" (1:144). Each of these details is repeated in the description of Caterina which opens the retrospective section of the narrative in chapter 2, so that the reader seems to reach the past by watching a portrait come to life. Ecphrasis connects the different time levels within the story, establishing a historical continuity.

The illusion of portraits coming to life likewise governs the introductions of Sir Christopher and Lady Cheverel. They own and thoroughly resemble two portraits of themselves by Reynolds (2:163), which are modeled upon the Newdigate portraits by Romney that George Eliot saw at Arbury Hall. Lady Cheverel, for example, looks "as if she were one of Sir Joshua Reynolds's stately ladies, who had suddenly stepped from her frame to enjoy the evening cool" (2:150), while Sir Christopher "was a splendid old gentleman, as anyone may see who enters the saloon at Cheverel Manor, where his full-length portrait, taken when he was fifty, hangs side by side with that of his wife . . ." (2:153).

Left: Sir Peter Lely, Sir John Skeffington, Viscount Massareene. Arbury Hall, Nuneaton, Warwickshire. Right: Sir Peter Lely, Mary Bagot, Wife of Sir Richard Newdigate, 2d Bart. Arbury Hall, Nuneaton, Warwickshire. Figures 4 and 5 in print version..

Both pictorially and historically, the Cheverels are in touch with the family heritage represented by the pictures that hang throughout the manor. In an upstairs gallery are "queer old family portraits — of little boys and girls, once the hope of the Cheverels, with close shaven heads imprisoned in stiff ruffs — of faded, pink-faced ladies, with rudimentary features and highly-developed head-dresses — of gallant gentlemen, with high hips, high shoulders, and red pointed beards" (2:168). Downstairs, in the main drawing room, hangs "a portrait of Sir Anthony Cheverel, who in the reign of Charles II was the renovator of the family splendour, which had suffered some declension from the brilliancy of that early Chevreuil who came over with the Conqueror" (2:165). Opposite Sir Anthony is a handsome picture of his wife. These two portraits are modeled upon Lely's full-length portraits of Sir John Skeffington, nephew of Sir Richard Newdegate, 1st Bart. and Mary Bagot, wife of Sir Richard Newdegate. 2d Bart., which still hang in the drawing room at Arbury [68/69] Hall (figs. 4, 5).50 They complement the pictures of Sir Christopher and his lady, and help to symbolize the continuity of the family from the Norman Conquest until the eve of the French Revolution.

But this pictorially reinforced sense of tradition and identity is in jeopardy. Sir Christopher, like Sir Hugo Mallinger in Daniel Deronda, has no son; and his heir, a nephew, expires of a weak heart before producing a male successor. Hence the dramatic irony of Sir Christopher's remark to his nephew early in the story: "You see, Anthony, I am leaving no good places on the walls for you and your wife. We shall turn you with your faces to the wall in the gallery, and you may take your revenge on us by-and-by" (2:162). Despite his neoclassical and sculpturesque good looks, Anthony finds no place on the wall, thereby initiating a motif that reappears in George Eliot's later fiction.51 In Felix Holt and Daniel Deronda, the younger generation also lose contact with a venerable portrait tradition of which the older generation are the last representatives.

Caterina Sarti's relationship to the Cheverel family and its portraits reflects George Eliot's ambivalence toward the aristocratic upper class. Caterina, the orphaned daughter of an Italian music master, loves Anthony Wybrow, the Cheverel heir, and passionately desires to marry him. They often meet secretly in the upstairs portrait gallery, a favorite haunt of Caterina's and a setting that befits her desire to become a member of the family. (A gallery located over cloisters is a recurrent setting in George Eliot's country houses. It appears in "Mr Gilfil's Love-Story" (chap. 2), Adam Bede (chap. 22), and Daniel Deronda (chap. 16) She sometimes looks 'like the ghost of some former Lady Cheverel" as she walks there (2:168). But the marriage is impossible, because Wybrow is merely toying with her affections and because no one in the family accepts her as a social equal. Although the Cheverels have reared Caterina, they have never adopted her, and they think of her more as a performing pet than as a daughter. The gulf that separates her from the family is rendered in pictorial terms as she sits in the drawing room one morning, thinking of Anthony's impending marriage to Miss Assher: "She sat with the book open on her knees, her dark eyes fixed vacantly on the portrait of that handsome Lady Cheverel, wife of the notable Sir Anthony. She gazed at the picture without thinking of it, and the fair blonde dame seemed to look down on her with that benignant unconcern, that mild wonder, with which happy [67/70] self-possessed women are apt to look down on their agitated and weaker sisters" (11:252-53). The self-possession of Lady Cheverel's portrait is shared by the portrait of her husband, Sir Anthony: "A very imposing personage was this Sir Anthony, standing with one arm akimbo, and one fine leg and foot advanced, evidently with a view to the gratification of his contemporaries and posterity" (2:165). The condescension of the portrait is typical of the whole family's attitude toward Caterina.

Her jealous love eventually turns into a murderous hatred, and although this passion remains focused upon the treacherous Anthony, it is at some level a hatred of the entire family. The impulse first takes the form, appropriately enough, of an attack upon a portrait. Caterina smashes a miniature of Wybrow, cracking his face and only just suppressing an urge to "grind it under her high-heeled shoe, till every trace of those false, cruel features is gone" (12:269). She nearly murders him in effigy, just as later she nearly murders him in fact. The logic of the literary portraiture in the story makes her assault upon the miniature a symbolic assault upon all of the Cheverel family pictures. Earlier the narrative implied that Caterina's passions may be equated with the passions of the French Revolution.

Caterina's relationship to the Cheverel family pictures anticipates Hetty Sorrel's relationship to the Donnithorne family pictures in Adam Bede. Hetty's social aspirations are expressed in her desire to "make herself look like that picture of a lady in Miss Lydia Donnithorne's dressing-room . . . she pushed [her hair] all backward to look like the picture, and form a dark curtain, throwing into relief her round white neck. Then she put down her brush and comb, and looked at herself, folding her arms before her, still like the picture" (15:224). When Hetty later puts a rose into her hair, Adam immediately identifies her model, though he does not approve of it: "that's like the ladies in the pictures at the Chase; they've mostly got flowers or feathers or gold things i' their hair, but somehow I don't like to see 'em: they allays put me i' mind o' the painted women outside the shows at Treddles'on fair" (20:335-36). Adam rightly intuits that Hetty's ambition to become a Donnithorne lady will involve her in a form of prostitution and a fall in social rank.54

Like Hetty, Esther Lyon, the heroine of Felix Holt, has always wanted to be a fine lady. She dreams of living in the style of the Transomes of Transome Court. Her wishes seem to be coming true when she is discovered to be the true heiress to the Transome estates and is subsequently sought in marriage by Harold Transome. But Esther's initial ambition gradually changes to a [70/671] recognition that the inheritance is tainted and compromising, and her moral growth is mirrored in her responses to the family portraits at Transome Court. One morning her suitor finds her in the drawing room, "looking at the full-length portrait of a certain Lady Betty Transome, who had lived a century and a half before, and had the usual charm of ladies in Sir Peter Lely's style" (40:216). Harold, who himself looks "like a handsome portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence" (46:309), immediately associates the two women, and tells Esther that she looks as if she were standing for her own portrait. The unspoken question in the scene is whether Esther will marry Harold and thereby take a place on the wall beside Lady Betty.

But Esther senses some danger in that destiny, for she observes that "almost all the portraits are in a conscious, affected attitude. That fair Lady Betty looks as if she had been drilled into that posture, and had not will enough of her own ever to move again unless she had a little push given to her.... One would certainly think that she had just been unpacked from silver paper" (40:216). Here Lely's mannered style is read as a sign of precious artificiality in his aristocratic subject. The portrait is a warning to Esther, and later in the novel she comes to understand what the family pictures are trying to tell her. Shortly before receiving Harold's proposal of marriage, she contemplates the ironic image of Mrs. Transome "in the evening costume of 1800, with a garden in the background" (42: 236). The discrepancy between the "youthful brilliancy" of this portrait and the "joyless embittered age" of the Mrs. Transome she has known helps to influence Esther against a loveless alliance of her own (49:332-33). Unlike Caterina, Hetty, and Gwendolen Harleth, Esther realizes in time to be saved from grief that what the English portrait tradition represents is not worth having at the price of alienation from herself and her class background; See Coveney, pp. 48-50.

In Daniel Deronda the Mallinger family heritage is symbolized by the portrait collection in the Abbey, Sir Hugo Mallinger's ancestral home. The pictures descend in an unbroken line from the reign of Elizabeth to that of George IV:

Two rows of these descendants, direct and collateral, females of the male line, and males of the female, looked down in the [71/72] gallery over the cloisters on the nephew Daniel as he walked there: men in armour with pointed beards and arched eyebrows, pinched ladies in hoops and ruffs with no face to speak of; grave looking men in black velvet and stuffed hips, and fair, frightened women holding little boys by the hand; smiling politicians in magnificent perruques, and ladies of the prize-animal kind, with rosebud mouths and full eyelids, according to Lely; then a generation whose faces were revised and embellished in the taste of Kneller; and so on through refined editions of the family types in the time of Reynolds and Romney, till the line ended with Sir Hugo and his younger brother Henleigh.... In Sir Hugo's youthful portrait with rolled collar and high cravat, Sir Thomas Lawrence had done justice to the agreeable alacrity of expression and sanguine temperament still to be seen in the original, but had done something more than justice in slightly lengthening the nose, which was in reality shorter than might have been expected in a malinger. [16:246-47]

Sir Hugo seeks to augment the family pictures when, near the end of the novel, he advises Hans Meyrick to give up history painting and turn to society portraiture, beginning with a picture of Sir Hugo's "three daughters sitting on a bank . . . in the Gainsborough style" (52:152). This anachronistic request, which is carried out later in the novel, places Sir Hugo's descendants in a pictorial tradition that died with Lawrence in 1830. (On the change in English portraiture after 1830, see Piper, p. 255.) As in "Mr Gilfil's Love-Story," the heir of the family perishes before his picture can be added to the collection.

Literary portraits, then, remained indispensable to George Eliot's presentation of character. For her, the process of knowing another person begins in pictorial first impressions. Even if those impressions prove to be inaccurate or deceptive, they form the cognitive basis for subsequent adjustments of comprehension. Portraiture is not, to be sure, a satisfactory medium for the representation of living, changing human beings; but it is a necessary starting-point for such representation, In addition to their cognitive function, moreover, Eliot's portraits often have an exemplary function. They depict humanity not only as it is but also as it should be. The next chapter will consider her pictorial idealization of character.

Created 2000; reformatted 2007 and 14 April 2015