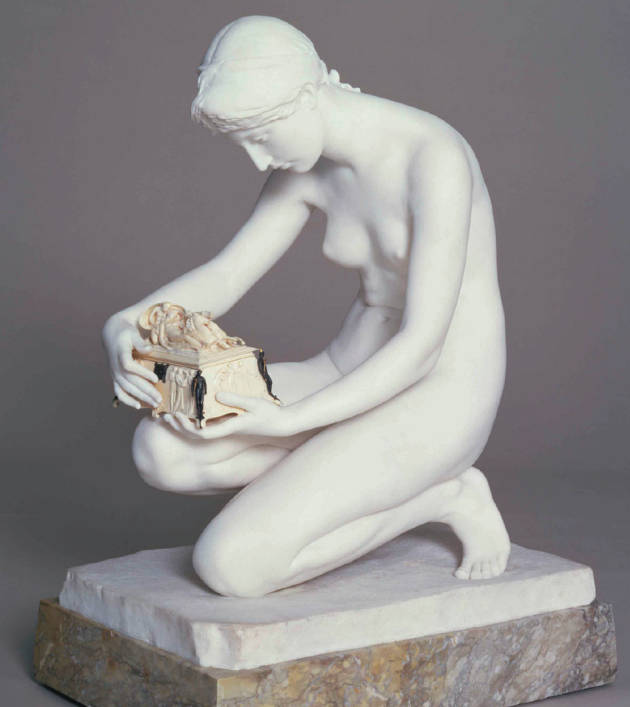

Pandora. c.1890. Marble, ivory, bronze and gilded bronze, 37 inches (94 cm) high. Inscribed “Harry Bates. Sc.” on back. Collection of Tate Britain. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Pandora is one of Bates's first ventures into three-dimensional statuary and is arguably his most iconic, as well as one of his most highly regarded, sculptures. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1890 [no. 2117] and subsequently purchased by the Chantrey Bequest for the Tate Gallery in 1891. Robert Upstone has noted that the pose is “an adaptation of a classical precedent, the much-copied and illustrated Crouching Venus in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence” (200). The finished work is an example of "chryselephantine" sculpture where the work is made of other materials in addition to marble, in this case ivory, bronze, and gilt bronze. Bates would have encountered examples of using such mixed materials for sculpture during the time he spent training in Paris. The pensive and introspective mood of Pandora is not unlike the works of Jules Dalou under whom Bates had studied, first in London and then in Paris.

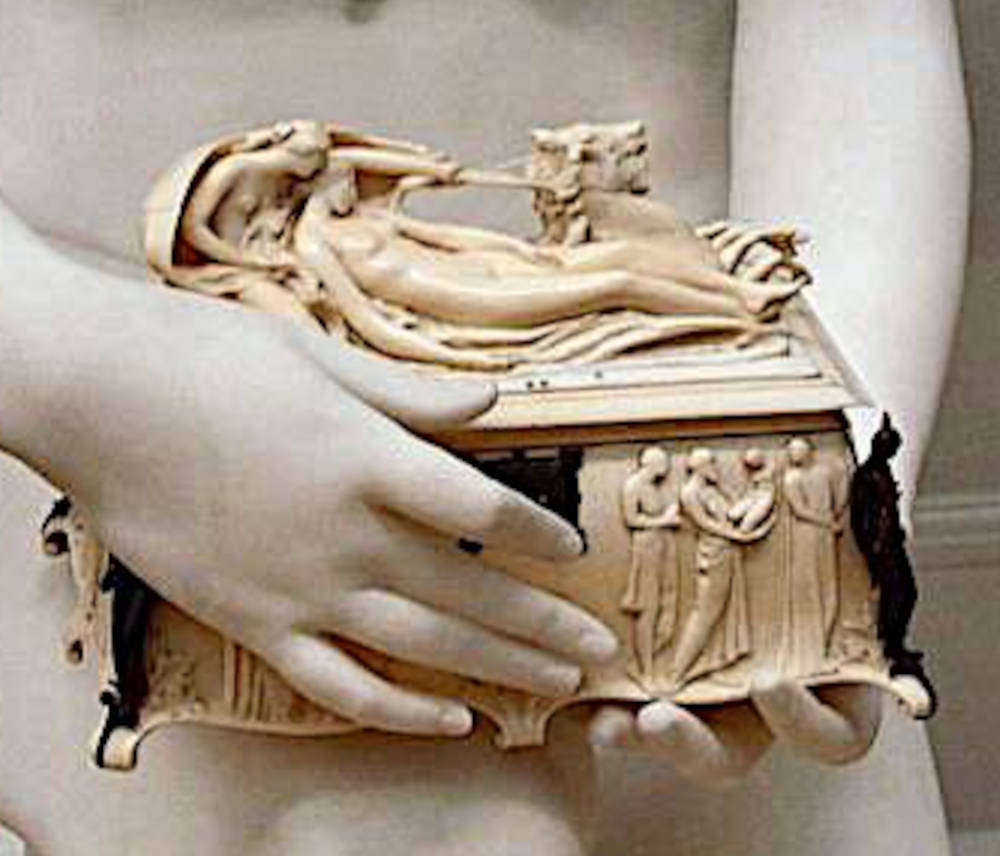

In Greek mythology Pandora was the first mortal woman. She was created at Zeus' orders by the blacksmith Hephaestus in order to enact revenge on mankind after Prometheus leaked the secret of fire. The gods gave her various gifts - Aphrodite gave her beauty, Apollo conferred the gift of music, while Hermes granted her boldness. Zeus decreed that Pandora should not only be beautiful but curious, impulsive, and imprudent. Zeus bestowed upon her a box containing all the evils and troubles of mankind as her dowry and sent her down to Earth. Zeus ordered Pandora never to open the casket and when she dishonoured Zeus by disobeying his orders and opened the box, all the misfortunes that could afflict mankind flew out. Bates’s ivory box was elaborately carved with scenes relating to the creation of Pandora. Because of his innovative use of polychromy and his allusive subject matter, Bates is often considered as one of the primary representatives of international Symbolism within British sculpture. Bates presents Pandora as yet another example of the femme fatale in late 19th century art. His sculpture is reminiscent of J. W. Waterhouse’s later similar paintings, Pandora of 1896, and Psyche Opening the Golden Box of 1903. In both these paintings, however, Waterhouse portrays the nymph draped and not nude, and slightly later in the story precisely as she is about to open the forbidden casket leading to the inevitable fulfilment of the myth. In Bates’s sculpture he portrays the temptation, as well as the moment of hesitation, just prior to when Pandora opens the forbidden box. She kneels over the box, with her right hand and wrist fully enveloping its form. Her pose, with all her weight balanced on the balls of her feet, lacks stability. Bates possibly intended this to suggest the instability of her situation and thereby portend the consequences of her subsequent action. On the lid of the box Pandora is carved in the round, reclining asleep in the arms of Zeus’s messenger Hermes, held between creation and life, in the chariot that will conduct her to earth.

When Pandora was shown at the Royal Academy in 1890 it was favourably received. The reviewer for The Magazine of Art commented: “If there were awarded by the Academy a Medal of Honour similar to that conferred by the Salon, it would with great propriety fall on this occasion to Mr. Harry Bates for his beautiful ‘Pandora,’ the most important work which he has yet executed in the round. The nymph is shown kneeling, entirely nude yet divinely chaste, as in awe-struck contemplation she holds before her the fatal casket from which is to issue all human woe. This casket is curiously fashioned of gold and ivory, after the manner of the chryselephantine statues of ancient Greece – an introduction of warmth and colour which at once suggests the necessity for a complete polychromatic system of surface decoration. The statue is just tinted a yellowish-white, so as to tone down the crude whiteness of the marble…The modelling is correct and unobtrusive rather than searching and masterly; the harmony of line and arrangement perfect, save perhaps for a certain excess of parallelism between the curves of the arms and those of the body and lower limbs” (364). F. G. Stephens, the critic of The Athenaeum, stated: ”Among the finest pieces of sculpture we expect to see at the Royal Academy this year is Mr. H. Bates’s life-size nude ‘Pandora,’ in which the artist has given a fresh reading of the subject, and instead of the customary elf-like or voluptuous woman has shown a tender, very gentle and happy maiden, whose features are charming. She is kneeling on one knee, and holds daintily with one hand the fateful casket, that is closed with hinges and a lock of gold. Her face is bent towards the coffer, which she regards with a brooding and almost wistful look, but without alarm or thought of evil. The virginal elegance of the figure, its graceful, spontaneous, and natural air, the simplicity of the attitude, and the finish of the whole work more than justify the reputation of the sculptor. The casket, which is made of ivory, bears upon the lid a beautiful group of Pandora descending earthwards, and carved upon its sides in low relief are panels representing scenes in her history” (443).

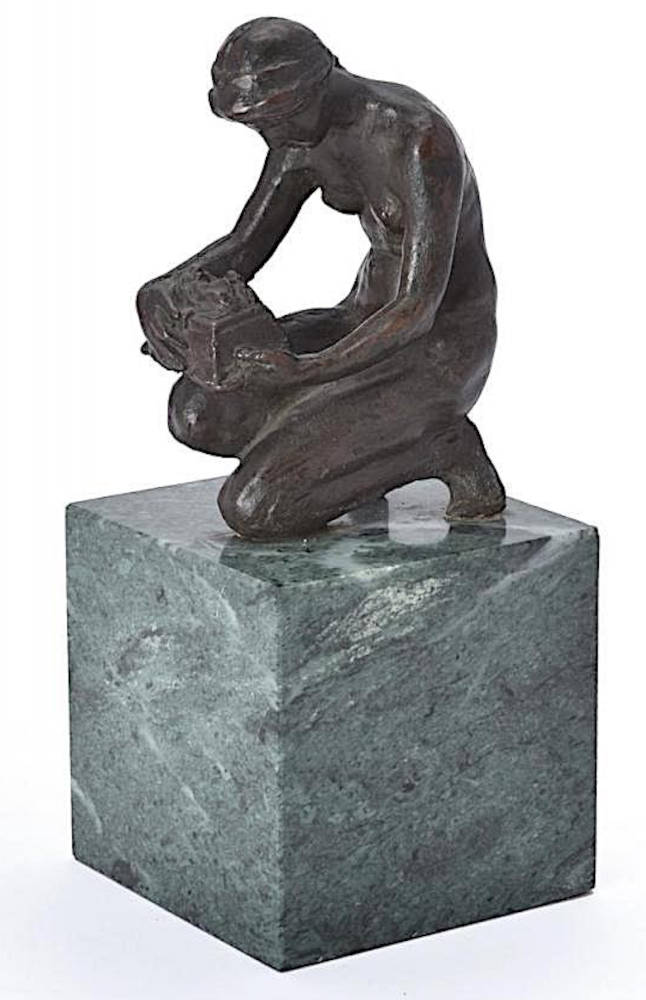

The Maquette

Pandora. Bronze maquette, 3 ¼ (8.3 cm) high, 6 inches (15.2 cm) high including marble plinth. Private Collection.

The whereabouts of the original plaster for Pandora is unknown and it may have been destroyed. A bronze maquette for the sculpture is in a private collection. The loose modelling and textural surface of the maquette is in contrast with the impeccably smooth surface of the large marble version and may reflect Bates’s training under Rodin. The maquette may possibly have been cast for Bates by Conrad Bührer (1852-1937), who is known to have also cast works for Frederic Leighton, Alfred Gilbert, Henry A. Pegram, and Thomas Stirling Lee. In the early 1890s Bührer occupied an adjacent studio to T. S. Lee in Manresa Road in Chelsea and also had a foundry at Hampstead.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one.]

Bibliography

Beattie, Susan. The New Sculpture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983. pl 147.

Bowman, Robert. Sir Alfred Gilbert and the New Sculpture. London: The Fine Art Society, 2008. Pp. 6-7.

Getsy, David. “Privileging the Object of Sculpture: Actuality and Harry Bates' Pandora of 1890.” Art History 28 (2005): 74-95.

The Magazine of Art. “Sculpture of the Year.” 13 (1890): 361-366.

Stephens, Frederic George. “Fine Art Gossip.” The Athenaeum No. 3258 (April 5, 1890): 443-44.

Upstone, Robert. Exposed the Victorian Nude. Ed. Alison Smith. London: Tate Publishing, 2001. cat. 128.

Last modified 18 May 2021