Oh I do like to be beside the seaside,

I do like to be beside the sea,

I do like to stroll along the prom, prom, prom

Where the brass bands play

Tiddly-on-pom-pom!

So just let me be beside the seaside,

I'll be beside myself with glee;

And there's lots of girls beside,

I should like to be beside,

Beside the seaside, beside the sea. —

Music hall song, 1907, by John A. Glover-Kind (1880-1918)

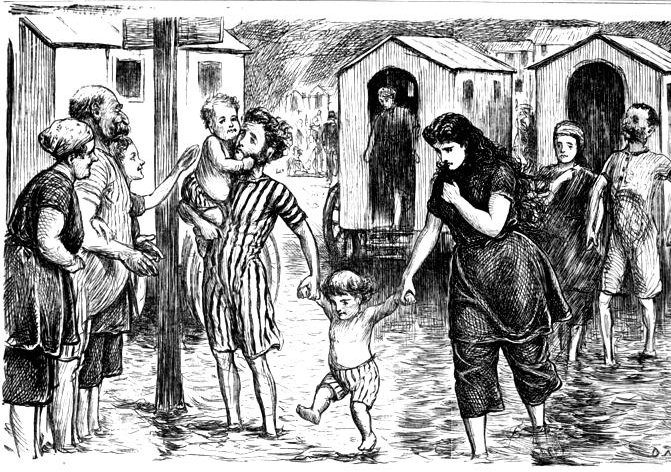

The Victorians loved to be beside the seaside. In a sense, they created it, as a great escape from the factories and cities which they had helped to build and in which many of them toiled for fifty-one weeks of the year. They took their new train-lines as close to the sea as they could, and made the trips down to and along the bays by horse-buses. They set up their bathing machines on the shore to preserve their modesty, built piers out to sea to get a bit closer to it and have more space for their entertainments, and developed a whole new industry — the seaside tourist industry, on the back of which hitherto little-known fishing villages, ports and lighthouse promontories flourished and burgeoned to become towns and even cities.

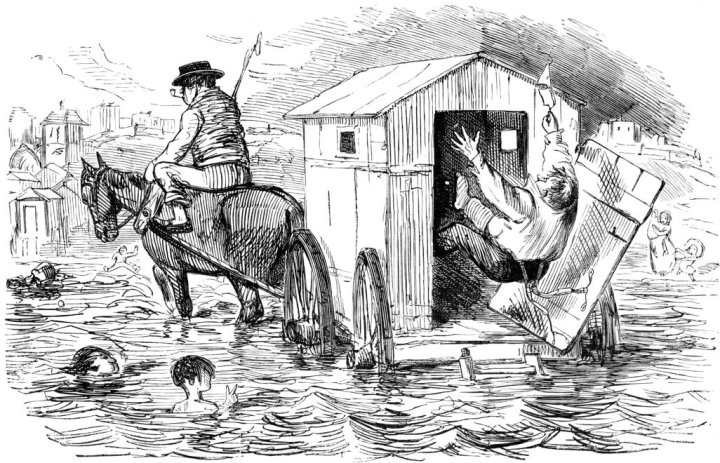

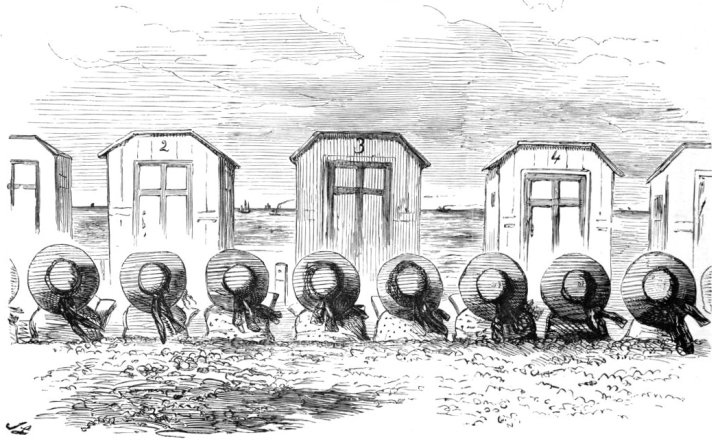

Three Victorian comments on bathing machines, the first and last by John Leech from Punch, the middle from The Illustrated London News. [Click on thumbnails for larger images]

Over the years, a unique culture grew up in these places, with their brass-bands, fairground attractions, music hall theatres, holiday food treats, nightly "illuminations" and so on. From grand resorts like Bournemouth, Brighton and Blackpool, to smaller ones like Whitley Bay, Newquay and Swanage, every coast of this island country had something to offer the trippers, and something to gain from them. It was all primarily for recuperation, leisure and recreation; but, being Victorians, the seaside visitors — especially those with pen in hand — often had higher cultural purposes in mind as well. For some, the seaside was a prime educational resource. It could also be an inspiration for their creative work, for its settings and its imagery, and for strange flights of fancy, whether humorous or (when clouds blew over the sunlit beaches and storms whipped up) for altogether darker imaginings.

Left: A Horse Bus to Pegwell Bay [Click on thumbnail for larger image]

Born in Devon and a skilled amateur naturalist, Charles Kingsley was a fervent advocate of natural history studies, believing this branch of knowledge to be mind-broadening and uplifting, and pleading for its inclusion in the school syllabus. Though he loved the seaside, he had, quite literally, no time for the idle pursuits of most other holidaymakers:

Follow us, then, reader, in imagination, out of the gay watering-place ... along the broad road beneath the sunny limestone cliff ... to the sea marge; for yonder lies, just left by the retiring tide, a mass of life such as you will seldom see again. [Glaucus; or The Wonders of the Shore (no chapter), 1855]

Three illustraions from Punch. Left: Scene on the English Coast by John Leech. Middle: Bain de Mer by George Du Maurier. Right: A very natural mistak by John Leech

He was not alone in guiding his readers away from the more frivolous enticements of the resorts towards the "sea marge." The first of Mrs Gatty's five volumes of Parables from Nature was published in the same year, and the parable entitled "Wheretofor?" instructs a child audience on the interdependence of the various living organisms to be found on the shore and in the sea. There are obvious implications for human life as well, for, after all, this is a "parable." Later, Kingsley was to use the water and its creatures in his own long parable for children, The Water-Babies (1863). Here, his chimney-sweep hero Tom is told of the sea which "lay still in the bright summer days, for the children to bathe and play in it" (Chapter 1), and is soon swept away into it himself to be cleansed of all physical and moral grime and deposited on sunlit shores, where a new lease of meaningful life awaits him.

Dickens too loved the seaside, but made use of it in a different way. He was staying in Yarmouth in 1848, and the Norfolk coastal town became an important setting for David Copperfield (1849-50); as if to derive further inspiration from the seaside, he was staying at Fort House in Broadstairs, on the Kent coast, when he finished the novel. In Chapter 3, he paints a magical picture of David and Little Em'ly running free on the beach, "picking up shells and pebbles," putting starfish back into the water, and exchanging a kiss "under the lee of the lobster-outhouse." This is a picture which reverberates through the whole narrative. As the narrator says,

I never hear the name, or read the name, of Yarmouth, but I am reminded of a certain Sunday morning, on the beach, the bells ringing for church, little Em'ly leaning on my shoulder, Ham lazily dropping stones into the water, and the sun, away at sea, just breaking through the heavy mist, and showing us the ships, like their own shadows. [Chapter 3]

It is, of course, the very picture of childhood innocence — but how do the details of this description draw attention to its vulnerability, and foreshadow the famous storm scene in Chapter 50?

Alice, the Gryphon, and Mock-Turtle by John Tenniel. [Click on thumbnail for larger image]

Another Victorian author who made regular trips to the seaside, and who wrote about childhood, was Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll). As a child growing up in the village of Croft by the River Tees, North Yorkshire, he had been taken on family trips to Whitby, the east coast resort with which Whitley Bay, further north, was apt to be confused. Later, Dodgson would haunt other seaside resorts, especially Eastbourne on the south coast, for the possibility of making and photographing new "child-friends." Despite its special attraction for him, he made fun of it in various ways, cocking a very obvious snook at the didactic approach of other children's writers. Consider the strange creatures which disport on the shore in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, and the contents of the sea itself, which is home to boots and shoes made of "Soles and eels, of course" (Chapter 10). As Jo Elwyn Jones and J. Francis Gladstone have said in The Alice Companion,

Carroll was not alone in getting comic mileage from the sight of people beside the seaside. The Victorians loved the seaside for the fresh air and sense of release it provided, but they also mocked their own enjoyment of it: there is something of this in "The Mock Turtle's Story" and "The Walrus and the Carpenter." It is strongly evocative of seaside cartoons in Punch, of men hunting for marine life in frock coats or, like the Walrus and the Carpenter, having long and serious conversations about salvation along the shores of an English beach. [p.232]

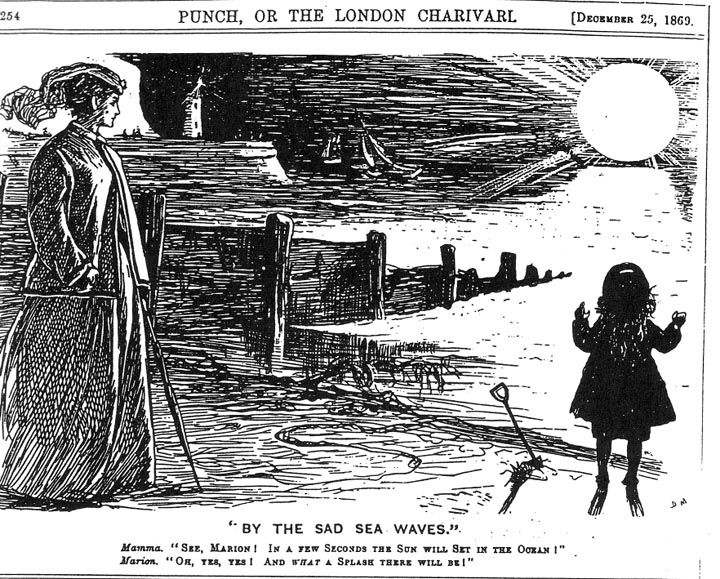

Left: By the Sad Sea Waves. Punch 1869. Right: Finis. (The End of the Season). Punch 1888. [Click on thumbnails for larger images]

A rather unseasonable Punch cartoon of 25 December 1869 shows the different kinds of impact the seaside could have on the Victorians. Entitled "By the Sad Sea Waves," it shows a little girl and her mother on the beach on a winter's afternoon. A suitably picturesque lighthouse is already emitting its beams in the background. "See, Marion!" says the mother, who probably wants to get the child back to a warm bed, "In a few seconds the sun will set in the ocean!" But the child, spade still stuck at half-mast in the sand beside her, is in no hurry to leave: "Oh, yes, yes!" she cries enthusiastically, waving her arms in the air, "And what a splash there will be! The title here echoes that of Chapter 16 in Dombey and Son, in which another Dickens child hero, that "old-fashioned" child Paul Dombey, dies after his own seaside visit, in a rush of watery imagery. The humour arises from the deflation of all the moralising and sentimentality surrounding Paul. Here is the healthy voice of Victorian scepticism reminding the Victorian public of what children on the beach are really like.

The Victorian response to the seaside was not always either nostalgic or humorous, any more than it was always didactic. The imagination could run riot there, and the danger lying in wait for innocence (whether Dickens's Ham and little E'mly, or Dodgson's unsuspecting whiting in "The Lobster Quadrille") becomes still more menacing in Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897). A substantial part of this is set in Whitby — the very same place that Dodgson had known as a child, and one which Dickens and Tennyson had both visited as well. Stoker vacationed there himself, and describes it in close detail in his best-known work. Significantly enough, though, his heroine Mina writes in her journal that her favourite spot there is the graveyard, "for it lies right over the town" (Chapter 6). The very next chapter opens with a newspaper account pasted into the journal: after a typical August Saturday at the resort, which was then bustling with trippers, a savage storm whipped up, and a strange schooner miraculously made harbour with a dead man lashed to its mast. (What might this account owe to the storm scene in David Copperfield, mentioned above?) But this is just the beginning for Mina and her friend Lucy, for the dead man was the heroic captain of the ship, while its "undead" passenger, Count Dracula, has leapt ashore safely in the form of a great dog. Obviously, Whitby is not destined to be a place of fun and frolics in this novel.

Dracula is hardly a representative seaside novel. Trips to the sands in childhood would continue to be a subject for nostalgic recall for many years to come, and the seaside postcard tradition still bears witness to the comic side of relaxing on the beach. Nevertheless, the Jungian use of the sea as a symbol of the collective unconscious, and Freud's analyses of childhood experience in general, would often endow the seaside in literature with a more profound significance. Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse (1927) and The Waves (1931) both come to mind in this context. But perhaps the most "Victorian" in feel of such early twentieth century novels is L.P. Hartley's The Shrimp and the Anemone (1944). Hartley was born in 1895, and this novel has its roots in the author's turn-of-the-century childhood holidays at the purpose-built Victorian resort on the Norfolk coast, Hunstanton. The powerful opening scene of the novel, like Chapter 3 of David Copperfield, shows the two young protagonists on the beach. Here, the power-battle between them, and its eventual outcome, are clearly prefigured when nine-year-old Eustace's elder sister Hilda pulls a shrimp from a sea-anemone: it is too late to save the shrimp, and the sea-anemone is also destroyed. In his New York Times review of the 1986 edition of Eustace and Hilda: A Trilogy, Michael North compares Eustace, who is left a legacy by the elderly Miss Fothergill, to Pip in Great Expectations (5 October 1986). Could Eustace be as usefully compared to any other Dickens hero or heroes?

Left: The Esplanade, Brighton, on a sunny summer's day.

Right: Brighton Pier. Photographs by Jacqueline Banerjee.

[Click on thumbnails for larger images]

As time went by, the nostalgia inspired by seaside outings in childhood would be further undercut not only by humour and a sense of personal embattlement, but also by changing social realities. Many resorts became increasingly shabby as they passed their Victorian heyday. This is reflected in the seedy and dangerous ambience of Graham Greene's Brighton Rock(1938), though, again rather typically, today Brighton has become vibrant and thrives once more.

Related Material

Sources

The Alice Companion: A Guide to Lewis Carroll's Books, London: Macmillan, 1998.

Hartley, Lesliey Poles. The Shrimp and the Anemone. London: Faber, 2003 (This is the first part of the Eustace and Hilda trilogy.)

North, Michael. "Worshiping Sis." See http://www.nytimes.com, and enter this title.

Glaucus, The Water-Babies, David Copperfield, Dombey and Son and Dracula are all available at Project Gutenberg.

Illustrated London News sketches kindly provided by Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council, as used in the Cotton Town digitisation project: www.cottontown.org

Last� modified 3 February 2011