inslow Homer is generally regarded as the greatest American artist of the second half of the nineteenth century. Never less than versatile and experimental, he worked initially as a ‘draughtsman on wood,’ producing a vivid record of the Civil War (1861–5) and other contemporary scenes; he later turned to painting idyllic landscapes, marine pieces and rural and working-class life in his own country and, for a period, in England.

Homer’s main focus, however, was always on America and became, in common parlance, an icon of American identity. As Randall Griffin remarks, his vision seemed to be ‘authentically national’ (89), making him into an ‘avatar of Americanness.’ Without doubt, this ‘wholly native’ (Cox 254) artist was an important contributor to American culture, and helped to define at least some of its characteristics as the nation emerged from the trauma of the Civil War and established its place as a unified sovereign power.

Homer’s imagery, in paint and on the printed page, was in this sense tightly framed by its contexts: he chronicled what America looked like, and he visualized what it meant to be an American. But Homer was equally concerned with the representation of wider themes, transcending the present and here-and-now. As recent critics observe, he was an ‘artist devoted to the world as it is,’ attempting ‘to record a particular time and place’ while also aiming to ‘visualize and dramatize broader social and philosophical [themes] that were at once timeless and timely’ (Byrd and Goodyear 1).

The complexities of Homer’s approach have been analysed in great detail in a large body of critical writing which began in his own time and continues to expand. Criticism has concentrated on his paintings, although there is a parallel body of scholarship exploring his illustrations. The aim here is to introduce his graphic designs, focusing on the features of his style while also considering his place as a nineteenth century book artist whose work, despite the avowals of uniqueness and freedom from European idioms, was influenced by British illustration of the period.

The Aesthetics of Realism

Homer’s fascination with the topical (or ‘timely’), and the ideal (the ‘timeless’), is clearly embodied in the 220 wood-engraved designs he did for American magazines – among them Harper’s Weekly, The Galaxy and Appleton’s Journal – in the years between 1857 and 1875. These illustrations mediate between the immediacy of current affairs and social mores, and deeper reflections on human feeling and the psychological impact of aspects of contemporary American life.

To explore the topical and every-day, Homer deploys a multifaceted realism. His primary approach is a journalistic recording of appearances in which he presents close, factual observations of the ‘actual material world’ (Johns 4), concentrating on details of setting, costume, décor, coiffure, landscape, and other physical or ‘natural’ accoutrements. One of his most famous images of the Civil War, A Sharpshooter on Picket Duty (Harper’s Weekly, 1862), was worked up from a painting, and exemplifies his verisimilitude. Depicting the figure as he sits in a tree and takes aim at an unspecified target, the image is anatomically exact: the character’s body, with his legs positioned so as to steady him for the shot, is clearly drawn from nature; his left arm holds on to a branch, and his right holds the rifle, finger on the trigger; his eyes look intently as he prepares to fire and his back is tensed to absorb the kick-back. This close observation validates the image, and Homer adds more to the sense of actuality by including the soldier’s water-canteen – casually hanging from the tree – while reproducing in fine detail the textures of the bark, the spikiness of the leaves, the creases in the character’s uniform and the insignia on his cap.

Homer’s most celebrated single image: A Sharpshooter on Picket Duty.

All of these elements convey the visceral immediacy of the now, providing a portrait of the life of the times, and Homer uses the same approach throughout his designs. It can be traced, for example, in his representation of contemporary dress in his many treatments of bourgeois fashion, as in Gathering Berries (Harper’s Weekly, 1874); and it provides a vivid portrait of rural life and the intricacies of trees, water and vegetation in Waiting for a Bite (Harper’s, 1874) and Snap-the-Whip (Harper’s, 1873).

Homer’s lyrical reading of America as a rural idyll, a place of plenty for all. Left: Gathering Berries; Right: Waiting for a Bite.

Homer’s Snap the Whip, an intimate portrait of country boys at play.

Speaking of his paintings, Elizabeth Johns notes how his images ‘come to us as marks of confidence in the importance of observation’ and their ‘ultimate reading of nature’ (5), and that judgment is equally true of his engravings on wood. Offered as transcripts, as if they were fingerprints of the ‘real’ world, their sensory intensity, one critic remarks, is ‘extraordinarily vivid’ (Weller 412), suggesting that ‘simple objectivity’ (444) is the artist’s primary aim.

This photo-journalism is often identified, and it has been argued by scholars such as Dana Byrd and Frank Goodyear that Homer was influenced by contemporary photography. He certainly worked from camera-images of politicians, turning them into wood-engravings, and seems to have been associated with Mathew Brady, the photographer of the Civil War.

Yet there were several other dimensions to Homer’s notion of realism as well. In addition to his cataloguing of the observed scene, he conveys the sense of the real in ways that go beyond the photographic print. He is especially adept at representing his illustrations as dynamic plays on movement; unlike contemporary photography, which was limited by long exposure times and could only produce static images, Homer’s realistic designs are fluent captures of energetic events.

Homer as the recorder of dynamic movement. Left: Winter at Sea; Right: The War for the Union.

This Baroque dynamism can be seen at its most extreme in Winter at Sea, with the mariners clinging onto the sail (Harper’s, 1869), in The War for the Union – A Bayonet Charge (Harper’s, 1862), with its depiction of a bayonet charge, and again in a related war-scene, illustrating Tennyson’s ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ (Gems of Tennyson, 1866). In these designs the artist uses fractured lines and sharp juxtapositions of fore and background to suggest movement, producing an intense impression of a fleeting moment. This is the effect late nineteenth century critics described as an expression of immediacy and ‘vigour’ (Linton 30).

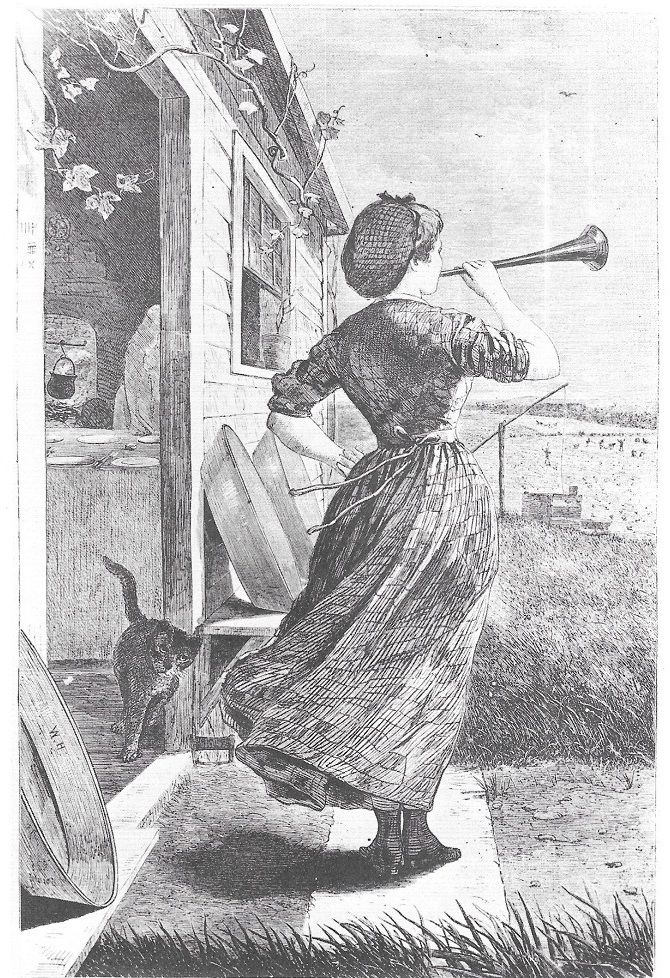

Two of Homer’s seemingly-spontaneous takes on the everyday, finding poetry in the banal. Left: On the Bluff at Long Branch; Right: The Dinner Horn.

Homer further nuanced his realistic approach by focusing on unexpected perspectives and small, unpredictable, or intimate details. In so doing he undermined the formality associated with art as conventionally understood, insisting on the value of the ordinary and prosaically tangible. On the Bluff at Long Branch (Harper’s, 1870) and The Dinner Horn (Harper’s 1870) exemplify these strategies. Both designs embody unexpected viewpoints, showing female characters from the rear, with sharp spatial recessions leading into a far distance in front of them; the women’s dresses are lifted by the wind and in each case the faces are turned away, with one character blowing the dinner horn, and the figure in the foreground of On the Bluff shielding her eyes from the blown sand. Possessed by the movement of passing gestures, the personae are arranged in calculatedly jarring compositions, functioning as participants in visual transcripts of the ‘real’ which act in defiance of conventional notions of harmony and composition and seem, as many early commentators noted, to be artless. Indeed, some critics have regarded Homer’s journalistic approacha as a type of primitivism, absurdly labelling the designer as a ‘natural force rather than a trained artist’ (Cox 254). In pursuit of the fresh and immediate, Homer was undoubtedly an iconoclast, an artist with an unblinking eye who ‘constantly took chances’ with his illustrations and continues to ‘surprise’ his viewers (Tatham 8).

One of Homer’s representations of the modern, East coast America, an urban domain standing in sharp contrast to the ruralism of most of the nation: Come!.

Homer’s approach is of course entirely appropriate to the medium of the weekly periodical, asserting an immediate response to the facts of modern living. Harper’s, Leslie’s and Ballou’s Pictorial were vibrant records of the times, and Homer’s designs stressed the connection between the journals’ reports and real life by visualizing its complex, ever-shifting, dynamic ordinariness. The written texts interpreted that contemporary world, and the illustrations gave it material form. The ephemeral nature of the readers’ experience is summarized visually by Homer’s Come! (The Galaxy, 1869), in which a couple look at each other as the women departs in a carriage and she extols him to visit her. Once again, the composition is startlingly direct and dynamic – a glimpse from within the vehicle as it starts to move. This, indeed, is a showing of the nuts and bolts of American life, animated with the vitality of the urban, modern cities of the eastern states.

Political and Moral Themes

Homer’s depiction of the ‘timely’ was matched by his focus on the ‘timeless’ (Byrd and Goodyear 1), enshrining reflections on human experience in American and general terms in what might appear to be a purely ephemeral depiction of a passing moment. In his illustrations, as in his paintings, this attempt to visualize ‘social and philosophical’ issues and questions (1) takes diverse forms and focuses on a number of key concerns.

A pronounced interest is the nature of conflict, a theme anatomized in his treatment of warfare. Though topical, Homer’s representation of armed struggle is infused with, and comments upon, a greater sense of the grotesque pointlessness and horror of military conflict. A little-known, but telling representation is embodied in his design for Tennyson’s ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ (1866) in an American version of the famous ‘Moxon Tennyson’ of 1857. Homer depicts a moment when one of the unfortunate cavalry men is pinned down by his dead horse, visualizing a scene which does not appear in the poem but is implied by Tennyson’s writing of the ‘jaws of death’ and description of the impact of ‘cannon’ that ‘Volley’d and thunder’d’ as the soldiers are Storm’d at with shot and shell’ (Gems of Tennyson, 149). Homer intensifies the notion of arbitrary death – showing a cannonball about to strike the equestrian group – but projects the absoluteness of extinction by accentuating the horse’s inertia, showing the beast as if it were a lifeless object with its front legs together in the manner of a rocking-horse and its back legs awkwardly crossed. This is very much a symbol of the iniquity of war – its lack of dignity, and its absoluteness as it reduces life to lifeless thingness. The horsemen still alive surge forward in a dynamic lines, but their inevitable destruction is figured in the stillness of the foreground figures: to this end they will come.

Homer’s reading of Tennyson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade.

This anti-heroic treatment privileges the poet’s despair at the pointless destruction, but does nothing to represent his emphasis on the nobility of those struck down by the incompetence of their command. The poem does not appear in the Moxon Tennyson, and it is telling that it was not illustrated in any contemporary British imprint as seeming too controversial a subject. Homer, though, was unimpeded by the values of Victorian readers, who may have preferred Tennyson’s jingoism to his implied criticism, and shows the Charge of the Light Brigade unambiguously for what it was: a waste of life.

Homer’s critique of human conflict finds multiple other expressions in his treatment of the American Civil War in the long-running coverage offered by Harper’s Weekly. Homer was the journal’s primary war-artist and spent time on or near the various fronts, but his response to what he saw, working from the perspective of a Unionist, was far from idealized or partisan; always offering a ‘personal and selective’ (Beam 13) vision, he shows the fighting as a sort of madness, stripped of any notions of valour or heroism. In The War for the Union (Harper’s, 1862) he depicts a bayonet charge as a chaos of figures, enshrining the horror of fighting with blades in a linear composition of jagged angles, points, and anguished faces. His famous Sharpshooter on Picket Duty (1862) is likewise coolly observed: there is no sense of the soldier’s personality and he is shown purely as a functionary performing his duty – to kill without even having to confront the enemy. This approach is implicitly disapproving; the artist’s attitude is far from that of a propagandist, and offers nothing to reassure the Unionist audiences of the East. Harper’s presented itself in its subtitle as a ‘journal of civilization,’ and Homer’s treatment of the conflict is a visual assertion of its inhumanity and de-personalizing effect, the reverse of ‘civilization.’ The fact that he was unconstrained by editorial interventions suggesst he was in line with the magazine’s political position as America struggled to come to terms with an internecine war that lasted for four, seemingly endless, years.

Political symbolism:

Thanksgiving Day.

Homer is on more comfortable ground when he pictures the value of everyday routines, ordinary life, and the reassertion of peace. The war concluded when Lee surrendered to Grant on April 9 1865, and the artist marked the return to stability in his Thanksgiving Day – Hanging Up the Musket (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1865). Homer characteristically makes this a simple, ordinary event – but invests it with political and moral agency. The woman’s reflective stance suggests the trauma of the war, and the placing of the rifle beneath another, labelled 1776, implies that the latest conflagration is part of the country’s struggle to achieve nationhood.

Bourgeois idylls. Left: Skating; Right: At the Spring.

Homer’s visualization of the Civil War provides a detailed portrait of America in a period of conflict and transition. Thereafter he focused on the peace, and many critics have argued that without dramatic events and changes to stimulate his imagination he became complacent, and lost his acuity. Philip C. Beam epitomizes this judgement, noting how:

During the years following the Civil War, the American nation settled gradually into a pattern of life which was on the surface at least peaceful and prosperous. It was a mode in which Homer was comfortable. The wrenching problems of slavery and internecine war were over … Homer identified himself most readily with the attitude of the prosperous middle-classes on the eastern seaboard … With the new leisure and gentility, people were able to spend a good deal of time in outdoor games and recreation … With these pursuits Homer was, by temperament, in easy harmony. [17]

Some of Beam’s comments are just. Homer certainly provides a detailed record of bourgeois leisure and pleasure. Our National Winter Exercise – Skating (Frank Leslie’s, 1866), On the Bluff (Harper’s, 1870) and At the Spring: Saratoga (Hearth and Home, 1869) exemplify his portraiture of the middle-classes at play. Yet it is misleading to argue that in the Reconstruction era Homer was no longer interested in social and moral commentary. Rather, he continues his analysis of American society, simultaneously offering insights which have a broader resonance. Although Beam sees him post-bellum as a reporter of middle-class mores, he also considers issues of class and class difference, charting the character of a society as it embraced capitalism.

Political and social commentary: New England Factory Life.

This focus can be traced in the artist’s contrast of the beneficiaries of wealth and its producers. In New England Factory Life – “Bell Time” (Harper’s, 1868), he depicts the fatigued faces and poverty of an ill-dressed group of workers at the start of the working day; though responding to the bell, their gait and gestures are lifeless and they make no attempt to hurry; their lives, Homer makes clear in their miserable faces, is an unremitting fatigue, an imprisonment in work symbolized by the vastly enlarged image of a prison-like factory in the background. Such facts stand in stark opposition to the lifestyle of their social betters, and the dress and demeanour of the workers stand in absolute opposition to the elaborate costumes of the leisured classes featuring in At the Spring (1869), whose fashion-plate faces are only troubled by the process of drinking some water.

Homer’s characterization of the social classes highlights the differences between them and defines an economic system that parallels the class-system of Victorian capitalism. Homer seems to be in sympathy with the condition of the working classes, but, like his British counterparts at work in (The Graphic, only appeals to morality and conveys no sense of the need for political change. It is interesting, also, to note how Homer’s journalistic interest in the prisoners of industrialization was not extended to slavery. He does not he does not explore the plight of Black people at any length in his illustrations for the press – although he does address slavery, with moving effect, in paintings such as (A Visit from the Old Mistress (1876, Smithsonian Museum, Washington).

Clearly, Homer’s version of American society was predominantly White, with little sense of ethnic tensions, the struggle with Native Americans, and the development of the West. His version of American identity is limited by these omissions. Nevertheless, he adds other elements to his definition of nationhood in terms of its struggles and its social structures. He marks the distinction between town and country, urban and rural life, and he is especially telling in his representation of the engagement between Americans and the country’s landscapes and natural life.

Poetic Nature. The Fishing Party.

Some of his imagery can be described, as Beam observes, in terms of the pursuits of the middle-classes as they enjoyed beach life and rural leisure (21), a theme developed in The Fishing Party (Appleton’s Journal, 1869) and (Low Tide (Every Saturday, 1870). In these designs Homer points to the incongruity of bourgeois costumes in wild settings, a notion projected in The Fishing Party, in which over-dressed girls stand precariously on a jumble of rocks. However, the artist is more concerned with the spiritual relationship between his characters and the American landscape, presenting his own treatment of Romantic pantheism in a series of illustrations charting the lives of those who work the land – farmers, trappers, fishermen, lumberjacks – and others who commune with the natural world. Some of the most moving of these images are illustrations of boys and young men who are engaged in leisure activities which go beyond entertainment and have a deeper resonance. In Waiting for a Bite, for example (Harper’s, 1874), he shows a group in a wild landscape, framed by nature’s plenty in a dense catalogue of carefully specified water-plants, trees and vegetation; the atmosphere is still, but the waiting for a fish to bite is simultaneously a reverie, a union between the languid figures and the Romantic atmosphere of the setting. This imagery is Homer’s version of Henry Thoreau’s Transcendental perceptions of nature in Walden (1854) and echoes Huck’s descriptions of the idyllic wilderness in Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885, US edition). Homer is an artist of the turbulence and tensions of American life and culture, but in his representations of characters in landscapes he finds another America – a new wilderness, and, for some, a new Eden. Underlying all that is ‘timely,’ he finds a ‘timeless’ engagement with eternal nature.

Homer and His Influences

As noted earlier, Homer is often described as an artist of pure originality, whose work was a home-spun product of America, with no outside influences. This claim was largely advanced by American critics in the nineteenth century, who wanted, as part of the country’s desire to differentiate itself from Europe, to position the illustrator as a champion of the new state, the embodiment of freshness and freedom from the tired conventions of the Old World. An independent artist with limited formal training was an apt metaphor, symbolizing the self-made, self-reliant spirit of America, of starting from scratch with nothing but determination to carry it forward, and to some extent these early commentators judgments were accurate: Homer was a highly original artist, both in his subject-matter and in the particular ways in which he managed to fuse the immediate and the profound. No artist had shown the home-audience such a portrait of itself before his appearance on the artistic scene, and no other practitioner had done so with such dynamism and vividness.

But he was not, as Kenyon Cox believes, ‘wholly native,’ nor was his ‘accent’ (254) entirely American. Rather, he assimilated a variety of outside influences, synthesizing pre-existing styles and idioms to create his own, highly personal art. In his paintings he came under the spell of Japanese prints (Weller 445) – mirroring a well-marked tendency in the ateliers of Europe – and in his Cullercoats pictures painted in England he focuses on the lives of working people in emulation of the painting of the Frenchman Jules Bastien-Lepage and the style of the British Newlyn School. Furthermore, in his work as a whole he was bound by the realist aesthetics of English painting as it developed in the first part of the nineteenth century, practising a naturalism that was broadly related to British art.

More especially, his illustrations reflected the influence of British illustration; as David Tatham observes, the work of British illustrators ‘was strongly felt, even by Homer’ (27). Books and magazines from the other side of the Atlantic were freely available in America as imports or as American editions issued by publishers such as Harper’s of New York and Ticknor and Fields of Boston, and this material provided a rich source of visual ideas. Indeed, Homer develops his illustrations in a parallel trajectory to British graphic art and reflects its fluid aesthetic transitions. Alice Newlin comments on how his earliest designs for the page are done ‘in the conventional English style … distinguished … by good humoured liveliness’ (56), and there is no doubt that Homer’s pre-1860s illustrations are strongly reminiscent of the vital linearity and dynamism of George Cruikshank and John Leech.

Homer and the British ‘knockabout’ style of the period between 1830 and the late 50s. Left: Homer’s Class Day, at Harvard University; Right: Leech’s Awful Scene on the Chain Pier, Brighton.

When it comes to the 1860s, however, Homer’s style changes, morphing into a version of the academic formalism of J. E. Millais, George Pinwell, George Du Maurier and all of those practising the ‘poetic naturalism’ of the period. Homer would have had plenty of opportunities to scrutinize this sonorous style in The Cornhill Magazine, Once a Week and other periodicals of ‘the Sixties,’ all of which had American markets, and there are many examples of his responses to this style and its variants in which he recreates some of its key conventions. In George Blake’s Letter (The Galaxy, 1870), for instance, he produces a monumental female figure dressed in the latest middle-class costume and enwrapped in deep reverie, a type of composition that is closely linked to designs by Millais, Du Maurier and Mary Ellen Edwards. The British school’s combination of modernity and psychological drama is clearly a model for Homer’s approach, and a simple comparison clinches the point.

Homer and the British style known as the Sixties. Left: Homer’s George Blake’s Letter; Right: An illustration by M. E. Edwards which models the fusion of interiority, academic correctness, and contemporary dress.

Homer was further influenced by a subset of the Sixties design in the form of the ‘Idyllic School.’ Practised by J. W. North and Pinwell, who focused on English rustic scenes, this idiom is refigured by Homer in his treatments of American country life, although his imagery is more metaphysical than that of his counterparts, replacing the harshness of rural living, registered by North and Pinwell, with Romantic wonder. Again it is instructive to compare the two approaches.

Homer and the British ‘Idyllic’ style: Left: Homer’s Making Hay; Right: one of Pinwell’s rustic scenes.

These points of comparison with British illustration suggest that Homer was not as free from outside influences as some critics have argued. Nevertheless, his was a genuinely American voice – adopting and synthesising some aspects of pre-existing visual codes and recasting them in terms which while reminiscent of outside influences, are unmistakeably the work of a highly inventive and idiosyncratic designer.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Adams, H. C. Appleton’s Journal (1869).

Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion (1857).

The Cornhill Magazine (1860 – 1875).

The Graphic Weekly (1869 – 1880).

Harper’s Weekly (1857–1875).

Hearth and Home (1869).

The Galaxy (1870).

Once a Week (1859–1875).

Tennyson, Alfred. Gems from Tennyson. Boston: Roberts, 1866.

Secondary Sources

Beam, Philip C. Winslow Homer’s Magazine Engravings. New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

Byrd, Dana E. & Goodyear, Frank. Winslow Homer and the Camera: Photography and the Art of Painting. Brunswick: Bowdoin College, 2018.

Cox, Kenyon. ‘Winslow Homer.’ The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 11 (November 1910): 254 –256.

Griffin, Randall C. Homer, Eakins and Anshutz: The Search for American Identity in the Gilded Age … Winslow Homer, Avatar of Americanness. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania University Press, 2004.

Johns, Elizabeth. Winslow Homer: The Nature of Observation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Linton, William James. The History of Wood Engraving in America. Boston: Estes and Lauviat, 1882.

Newlin, Alice. ‘Winslow Homer and A. B. Houghton.’ The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin31, no. 3 (March 1936): 56–59.

Tatham, David. Winslow Homer and the Pictorial Press. New York: Syracuse University Press, 2003.

Weller, Allen. ‘Winslow Homer’s Early Illustrations.’ The American Magazine of Art 28, no. 7 (July 1935): 412 – 417.

Created 15 September 2023