Foreword

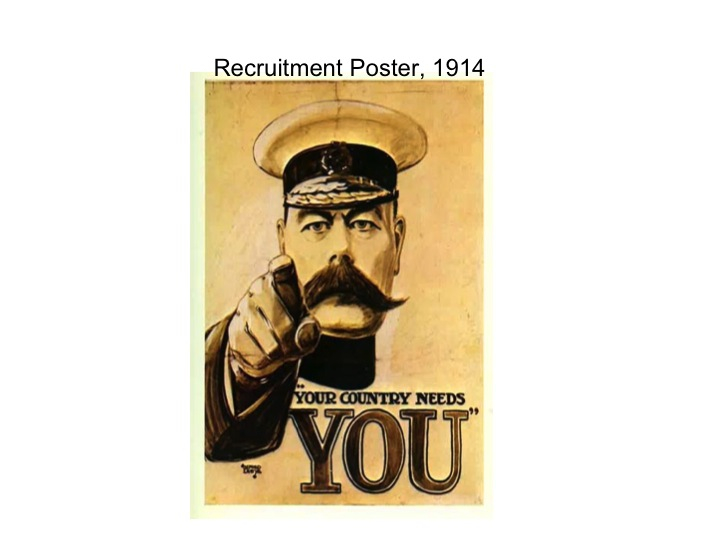

Although the term 'national service' was first used for conscription in World War II, I have used it in the title to refer to the Great War since it nicely encapsulates my argument. In its hour of need a country often invokes its great writers (as was Shakespeare in Laurence Olivier's film of Henry V, which was part funded by the government and released before the Normandy invasion of 1944), and in the early twentieth century that writer for Great Britain and the Empire was Dickens. One month after Great Britain declared war on Germany in August 1914, this famous recruitment poster appeared (1). I propose that the Secretary for War, Lord Kitchener, was pointing his finger at Charles Dickens (2) whose characters responded to their call-up by appearing in new textual forms that promulgated a particular version of Englishness (the subject of Part I). Part II examines the dissemination of that Englishness via pictorial representations of his characters in commercial products such as jigsaw puzzles, postcards, and cigarette cards.

Part I: New Textual Forms Promulgating the "Englishness" of Dickens

The decades before 1914 witnessed England's becoming increasingly anxious about its national identity, "when new commercial rivals [America and Germany] threatened Britain's industrial supremacy and faith in empire began to waver that a degree of English self-consciousness began to emerge" (Kumar 224). Perhaps the crucial event was the Boer War (1899-1902), "a blow to the country's self-confidence — [that left England with] — a lasting anxiety as to its power and status in the world" (Brooks 2). For Walter Crotch, President of the Dickens Fellowship, "it was during these two-and-a-half years that the Dickens renaissance took shape and form" (123), about the same time as "the moment of Englishness" (Kumar 174). "In one sense the Dickens renaissance was cultural compensation for the country's political decline, but in another it was a powerful instrument in the formation of a brand of Englishness for contemporary (and future) generations" (Cordery 22). Promoted mainly by the Fellowship and G. K. Chesterton, it was characterized by fellow feeling, by sentiment (pathos), by humorous eccentricity, and by the celebration of hearth and home, especially at Christmas. For Chesterton, whose influential Charles Dickens was published in 1906, the Dickensian Christmas embraced those "very English instinct[s]" of charity and comfort: "This ideal of comfort belongs peculiarly to England; it belongs peculiarly to Christmas; above all, it belongs pre-eminently to Dickens" (118). In his 1910 address to the Fellowship, "Dickens' Influence on National Character," its new President, J. Cuming Walters, asserted that Dickens "had become a moulder of character, and he had helped to strengthen the moral fibre of the nation — He represented the real Englishman" (320).

The conjunction of the Dickens revival with a crisis of nationhood led the Fellowship and its supporters to valorize those pre-1851 works that were seen best to express Dickensian Englishness: The Pickwick Papers, David Copperfield, and the Christmas Books of the 1840s. This is not the Dickens of the dark novels, the revealer of social evils and poverty, the savage satirist of government incompetence and ineptitude. Such a Dickens was anathema to a nation needing and demanding unity and co-operation from all and certainly not one to put before the men in the trenches. No, Chesterton and the Fellowship constructed a humane, moral and cozily domestic Dickens who would serve the needs of the nation and rally its people. It is no coincidence that the 1914 song "Keep the Homes Fires Burning" became virtually a national anthem during World War I. With music by Ivor Novello, himself a Royal Navy Air Service pilot, its lyrics (by Lena Ford) were nostalgically Dickensian:

Keep the home fires burning While your hearts are yearning Though your lads are far away They dream of home.

In 1915, the patriotic Daily Mirror suggested that "the Germans — Nietzschean supermen — could be bested by flooding their country with copies of A Christmas Carol, thus letting Tiny Tim loose on the hearts and minds of the 'Hun'" (qtd. by Maunder 191).

Be that as it may, real life Dickensians did indeed help defeat the enemy. GK's brother Cecil, was wounded three times in France, and said that if a visitor from another planet asked what was this England we were fighting for “the best answer he could make would be to present that visitor with a complete edition of Dickens' works and say: 'That is England'" (Dickensian, July 1915, 174). Killed in action, The Dickensian's obituary (October 1916, 276) of the novelist's grandson Cedric Charles, a major in the Kensington Battalion, ends thus: "in the spirit of an Englishman . . . was the blood of a Dickens — a name that stands for everything that the word English conveys — shed for the country and the cause his grandfather held most dear, and fought for as valiantly with his pen as his grandson did with his sword." The Dickens blood is literally shed on the fields of Flanders in defence of England and Englishness.

The Dickens revival at the turn of the century was indisputable. The founding of the Fellowship in 1902 (by 1909 its membership numbered 17,000 with branches worldwide), of its organ The Dickensian in 1905, and the centenary of his birth in 1912, were obvious markers. In addition to film and stage adaptations the commercial world was quick to seize upon Dickens's popularity: he and his characters appeared as ornaments, in advertisements ranging from Wright's Coal Tar Soap (Mrs. Gamp) to Robinson's Barley (Mrs. Micawber), on stamps, calendars, Christmas and menu cards, cake tins and biscuit boxes, as well as on jigsaw puzzles, postcards and cigarette cards. But what about the texts themselves?

According to Robert Patten, "Chapman and Hall alone sold 2,000,000 copies of his works between 1900 and 1906" (330). And once his novels were out of copyright (forty years after publication) new editions poured from the presses. Between 1893 and 1914, nineteen separate major editions were published, not to mention numerous cheap reprints such as those in Nelson's Sixpenny and Sevenpenny Libraries and W. T. Stead's Penny Novel series which, begun in 1896, had within eighteen months nine million copies in print, many by Dickens. They catered to the literate working classes (created by Foster's 1870 Education Act) who also borrowed from the increasing number of public lending libraries, begun in 1850 and termed by Dickens "the great free school," to which, by 1913-14, 79% of the urban population had access. "Over a third of the public libraries functioning by 1914 had emerged since 1900, over two thirds since 1890" (Waller 50) and the borrowers, according to Waller, were overwhelmingly working-class. David Vincent comments drily that "England managed to ensure that all its young men could read and write just in time to send them to their deaths in the trenches" (4).

By the outbreak of the Great War the Dickens renaissance had made available a reservoir of values, ideas, characters and images that could be drawn upon to inform and shape a growing sense of national identity, to boost the morale of troops and to relieve their boredom. But how, during the war, was Dickensian Englishness disseminated both at home and abroad, and in what formats was it textually consumed? Various organizations, both voluntary and governmental, were instrumental in spreading the gospel of Dickens.

Foremost, of course, was the Fellowship itself, which entertained wounded servicemen by giving recitals, concerts, readings, and Tiny Tim teas. A Fellowship favourite, Professor Miles, performed Dickens before the troops in France and Captain Corbett-Smith gave four recitals of A Christmas Carol to troops resting behind the trenches, one in a French barn "simply crammed full with men" (Dickensian March 1916, 70). [For more examples see White.] As well as endowing hospital beds and cots the Fellowship raised funds for a "Charles Dickens Home for Blinded Soldiers and Sailors" and set about producing a braille edition of the novelist's works, successfully completed in 1918.

Textual Dickens also found his way to the large number who lay wounded in hospitals and rest homes at home and abroad through quangos such as the YMCA, The Camps Library, the British Prisoner of War Books scheme and the British Red Cross War Library. (For these organizations and the distribution and reading of books during WWI, see Koch's invaluable account.) This last organization alone bought or received as gifts more than four million books and towards the close of the war "was supplying approximately 1810 hospitals in Great Britain" (Koch 179). Unlike those at the front the hospitalized wounded had time to read Dickens slowly from cover to cover. The honorary librarian of Wandsworth General Hospital relates that the men eagerly read "Scott, Dickens, Thackeray, and Jane Austen . . . I received last week a glorious present of a complete set of Dickens in the Gadshill edition, — noble volumes, scarlet bound, and a delight to look at and handle" (Koch 248).

But for Tommy Atkins trudging to the next battlefront, such weighty volumes would have been anything but a delight to handle. Henry Weston Farnsworth of the Foreign Legion writes in August 1915 that in camp he read Pickwick and Plutarch, but "books are too heavy to carry when on the move" (Koch 291). So the call was for small, cheap editions and so great was the demand that Liverpool booksellers reported "a famine of seven-penny and shilling books because of the demand for them from the trenches. 7,000,000 are said to have been sent to the front" (The Publishers' Weekly, 4 August 1917, 410).

It is not possible to calculate how many of these seven millions were by Dickens. A man from Montana, upon finding that works by Jack London and Zane Gray were checked out, was directed by a troopship’s librarian to a shelf of classics that included Scott, Thackeray, and Dickens. This he pronounced to be "a bum collection" (Koch 141). This anecdote, however, is hardly typical, since Dame Eva Anstruther, in charge of the Camps Library scheme, reported "that we are constantly asked for [Dickens'] novels from all units of the army" (Koch 226). The following should remove any doubt as to the wide circulation of textual Dickens during wartime. From a hospital near Gaza a son of a member of the Fellowship writes that the Nelson edition of A Tale of Two Cities he was reading was "sold by a bookseller in Utrecht and presented as a souvenir to a girl at Athens. It is now in the library attached to the Hospital, having been presented to the Australian Red Cross Society" (Dickensian, November 1917, 285). From England to Holland to Greece and finally to Egypt is a long journey, even for Sydney Carton.

In addition to cheap, small editions like Nelson's, light, portable reading matter was also catered for by the Broadsheets scheme run by The Times newspaper. The Broadsheets were a kind of Reader's Digest of the best bits of Eng. Lit., selected by Sir Walter Raleigh, Professor at Oxford, and the public was urged to enclose them with letters sent to soldiers overseas. Raleigh believed their appeal was enhanced when read abroad since "our fighting troops think more of England now than they thought of her when they were at home," a belief confirmed by a soldier "somewhere in France": the Broadsheets encourage "renewed astonishment and pride in the Old Country for the richness and variety of her literature" (Times, 23 December 1915, 6). Known as the "Fighting Men's Library," the brief passages were designed to boost morale and enhance the reader’s sense of his Englishness during "The Great War."

Of the grand total of 180 extracts, thirteen were from Dickens whose dramatic episodes lent themselves to such abstraction. The thirteen extracts were these: A Game of Cribbage (OCS); Mr. Micawber's Transactions (DC); Mr. Tony Weller on Literature (PP); Mr. Pecksniff at a Boarding House (MC); Mr. Skimpole and Coavinses (BH); Mr. Mantalini at Breakfast (NN); Mrs. Wilfer's Wedding Day (OMF); The Circumlocution Office (LD); Mrs. Lirriper on Lodgings (CS); General Choke and Queen Victoria (MC); The Election at Eatonswill (PP); The Crummles Company and the Drama (NN); Scrooge's Visitors (CC). An officer and his men billeted at a Flanders farm for the night, writes that "the Padre — read aloud three times to the men the 'Game of Cribbage between Dick and the Marchioness' and 'Mr. Micawber's Business Transactions'"(Times, 5 November 1915, 9). The same officer writes that "books are costly to convey and in a sudden advance it wrings the soldiers' hearts to jettison them." The Broadsheets, then, were ideal for troops on the move, and one even writes from Mesopotamia that "we can carry our pet passages in our helmets" (Times, 22 December 1915, 4).

Part II: Pictorial Dickens — Visual Forms Promulgating His "Englishness"

But even if a soldier had not actually read Dickens, he was probably familiar with his characters through non-textual forms. Instead of a broadsheet in his helmet he would have a cigarette lodged behind his ear. Since, so it is said, soldiering is ninety nine per cent boredom there was at the time "a never ceasing demand for playing cards, dominoes, draughts, and good jigsaw puzzles . . . . Anything that can be packed flat is acceptable" (Koch 7). To this list of boredom-reducing products can be added cigarette cards and postcards mailed from home.

So I turn now to the dissemination of Dickensian Englishness via the visualization of Dickens' characters and scenes in some of those leisure products likely to have found their way to the troops and non-combatants at home and abroad. In a sense, they became recruitment stations where the likes (and likenesses) of Heep, Pecksniff, Micawber and others arrived in their pictorial uniforms to answer Kitchener's call to national service. Their images look back to the originals by Cruikshank and Phiz, but with significant differences.

The following discussion confines itself to examples from postcards, jigsaw puzzles, and cigarette cards because certain historical conditions prior to the war promoted the wholesale production and distribution of these particular commodities, thus making them readily available for circulation among the troops. The zenith of the postcard craze was 1902-18 because only after 1901 were the address and message allowed on one side, thus releasing the reverse for an image. The picture postcard came into being. Jigsaw puzzles for adults emerged around 1900 and by 1908 a full-blown craze was in progress in the USA, which then migrated to England where Raphael Tuck produced the Ludovici Dickens coaching prints. Finally, cigarette cards first appeared in England in 1888 and major series by various artists of Characters from Dickens accompanied Players, Copes, and other brands between 1900 and 1919.

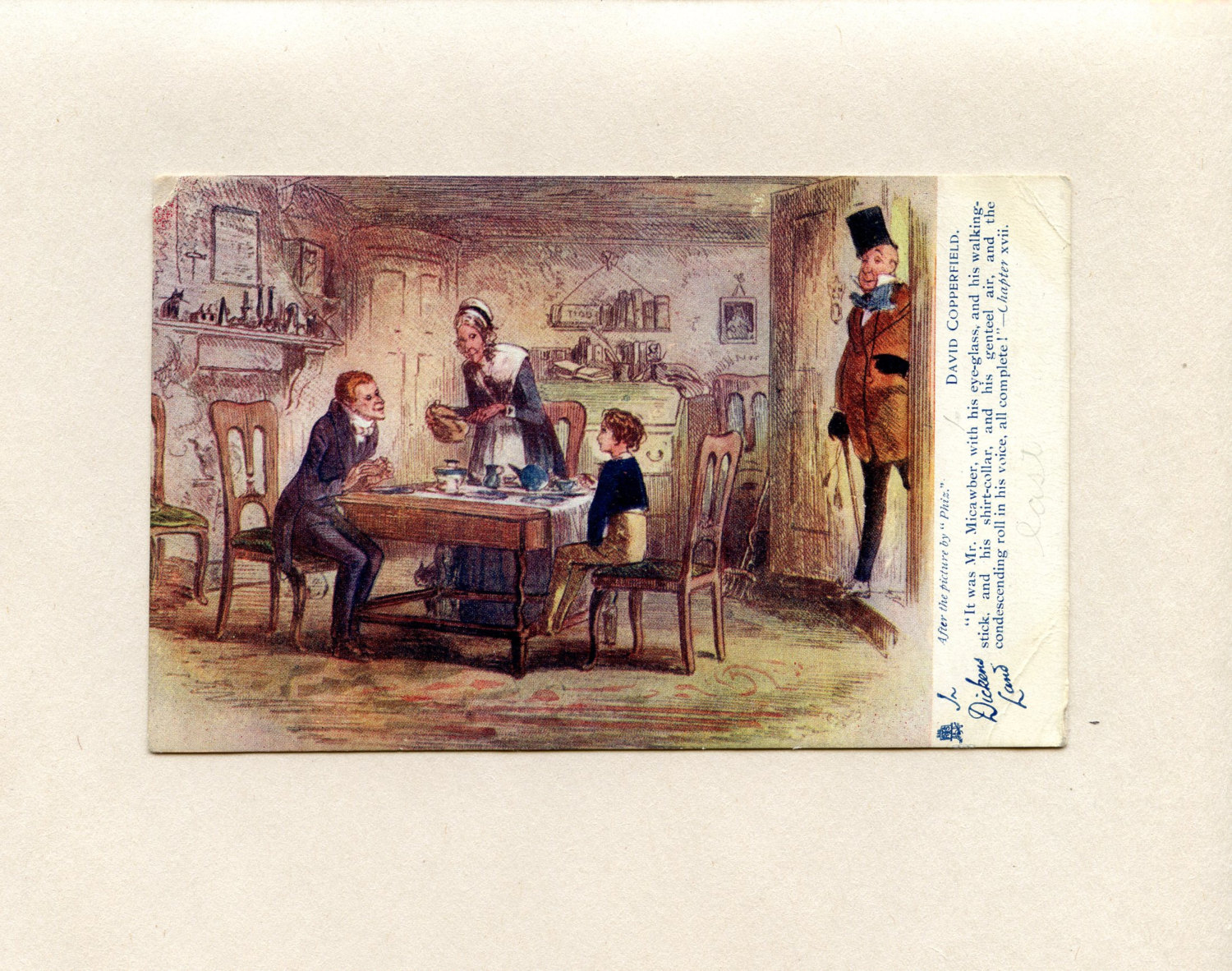

Since they drew upon illustrations by Cruikshank and Browne there is a clear family resemblance among these commercially produced images. A few did reproduce the originals, as in the In Dickens Land series of postcards reproduced by Raphael Tuck (3). These catered to diehard traditionalists, but many purchasers preferred the new realistic style of illustration inaugurated by Fred Barnard for the Household Edition of 1871-79. His triple series of lithographs and photogravures, Character Sketches from Dickens (1879-85), confirmed his reputation as the leader of a new group of illustrators who had sprung up after Dickens' death in 1870.

Suitable for framing (and so advertised), these beautifully produced portraits were reprinted in, for example, Cassell's Family Magazine in 1896, and re-emerged in Cassell's Art Postcard series of 1902 and 1906. Only three of a total of eighteen images came from the post 1850 novels while eight, almost half, came from just two novels, The Pickwick Papers and David Copperfield. The emphasis on humour, sentiment, the family, and individual eccentricity, is to be seen in Barnard's immediate successors (he died in 1896) such as Cecil Aldin (for example, Sam Weller Meets His Long Lost Parent), Frank Reynolds, Harold Copping, and the Clarke), to name but four of the sixty or more English and sixteen American artists who had illustrated Dickens by 1924. For these and other illustrators, see the entries on Victorian Web and especially Philip Allingham’s Extra Illustrations and Grangerising: A Dickensian Phenomenon."

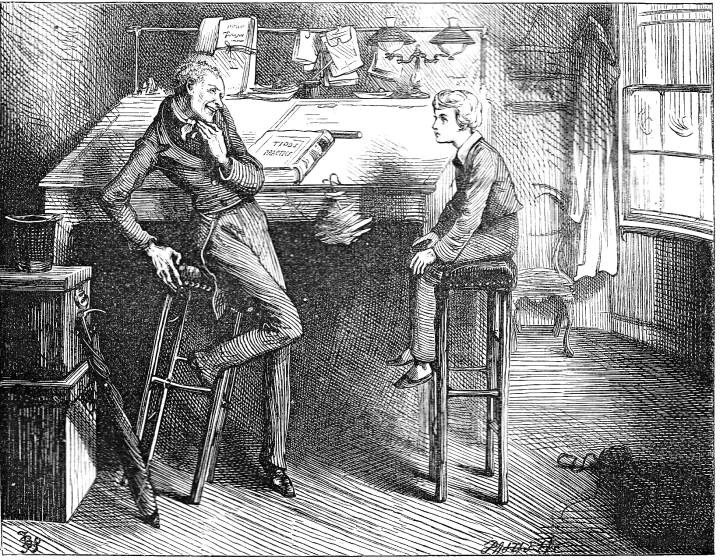

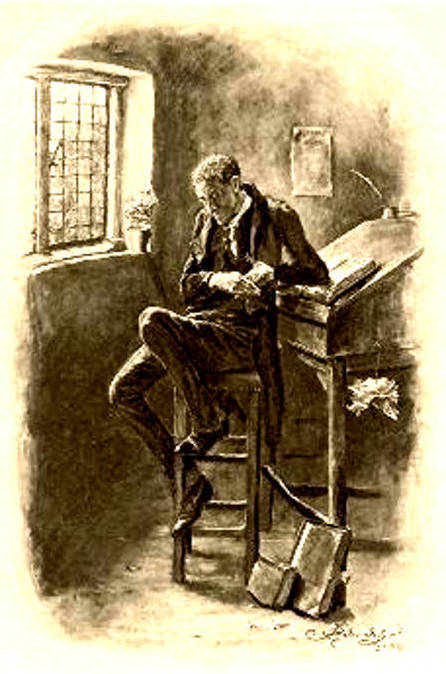

Left: Hablot Knight Browne's somewhat caricatural realisation of the scene in which the cheerful indigent Wilkins Micawber unexpectedly arrives on the Heeps' doorstep in Somebody turns up (October 1849). Right: Fred Barnard's realisation of the corkscrew movements of the "umble" Uriah when he meets David as a child, "Oh, thank you, Master Copperfield," said Uriah, "for that remark! It is so true! Umble as I am, I know it is so true! Oh, thank you, Master Copperfield!" (1872). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

As Dickens illustration moved towards a less caricatured, more realistic style, Barnard can be seen as a transitional figure. Compared to Kyd and his contemporaries, he retains a greater fidelity to the originals but there is still a reduction in complexity, symbolic detail, suggestiveness, and social milieu, which are all evident, for example, in Phiz's Somebody Turns Up (3), in which Mr. Micawber comes upon David at the Heep household, with its clutter of objects on wall, dresser and mantelpiece:

the corkscrewing [by Uriah] of facts about himself" out of David — the metaphor is Dickens' own — is indicated by the corkscrew hanging on the wall, the stuffed owl which implies the predatory watchfulness of the Heeps, the mousetrap, and even the ceramic cats, which, together with the real cat next to Mrs. Heep, could represent the Heeps' ability alternately to fawn and purr, and to hiss, spit, and scratch, or destroy a 'mouse'." — Steig, 120-121.

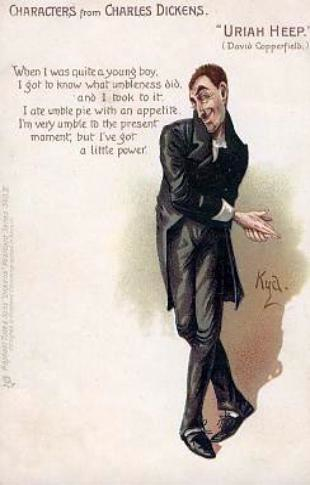

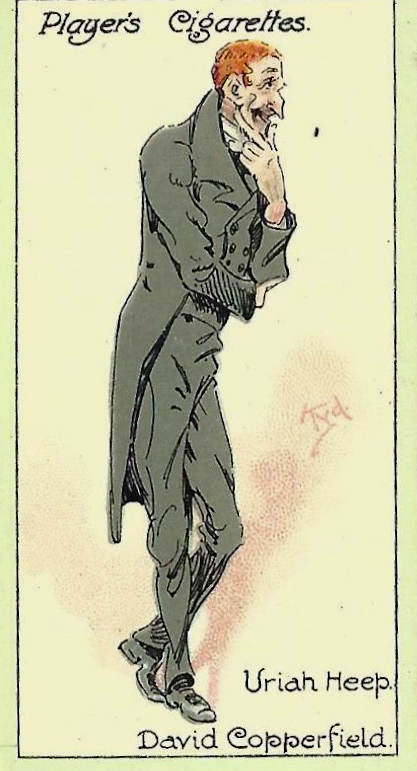

Left: Figure 5, the isolated image of "corkscrewing" Uriah from Barnard's Character Sketches from Dickens in the Cassell's 1902 series, Uriah Heep (1885). Centre: Figure 6, the Cassell's Art Postcard elaborates the earlier character studies, Uriah Heep (1905). Right: Figure 7, Clayton J. Clarke's commercial image of the smarmy villain in lithograph, Uriah Heep (Player's cigarette card, 1912). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In Barnard's depiction of the unctuous attorney's clerk for an 1872 wood-engraving (4) Heep's grotesqueness is retained, but the background detail is realistic rather than symbolic, and there are only two figures. After 1902 many of the same artist's Character Sketches from Dickens (1879-85) were reproduced on picture postcards. In a later Barnard representation, figure 5, Heep is by himself, his exaggerated distortions toned down, and Phiz's symbolic bric-a-brac absent. A 1905 postcard by Kyd (6) shows just Heep with no surrounding detail at all. Finally there is Kyd's 1912 sketch for Player's cigarettes (7).

Although these later depictions of Dickens' characters were marked by simplification and a lessening of caricature, all contact with the originals was not lost. Heep is still recognizably Uriah, and in successive images of Micawber the defining features of his dress — the top hat, the "imposing shirt-collar," the "jaunty sort of stick with a large pair of rusty tassels to it; and a quizzing-glass hung outside his coat" (David Copperfield, ch.11) — all present in Phiz's originals, are retained by Barnard, Kyd, and others for pre-World War I commercial products (figs. 8, 9, 10, and 11).

The watchword for these post-Dickensian illustrators was realism, a realism of both content and style, in keeping with the mores of the time. Polite society created a Dickens who, in the words of Marie Correlli, was "sane, true, human, wise, witty, and clean! — such a lot in that last word! Clean!!" (Dickensian, December 1918, 332). Kyd and his contemporaries rarely portrayed sexual predators from the earlier novels such as Carker or Steerforth. Instead, early villains are depicted as vicious brutes, though shorn of their degrading ugliness. Compare, for example, 12 with 13. Cruikshank's menacing Bill Sikes first appears, along with Nancy, apprehending Oliver before a crowd of disheveled onlookers in one of Cruikshank's richly detailed contemporary street scenes. Kyd's stand-alone portrait of Sikes (13) (Kyd does not include Nancy in either his postcards or his cigarette cards) offers the viewer a cleaned up, well turned out criminal: the "black velveteen coat" (Oliver Twist, ch. 13), spruce and well-fitted, covers a smart, patterned shirt; his "breeches" are hardly "drab" and certainly not "very soiled"; "the belcher handkerchief around his neck" is neither "dirty" nor "frayed"; the setting is not one of his usual haunts such as the slums of Saffron Hill, but a relatively bare room with solid furniture. This is hardly, as the caption to the postcard states, a study from life by Charles Dickens, but rather a romanticized version of a brutal murderer who seems to be posing for a studio portrait by Joseph Clayton Clarke.

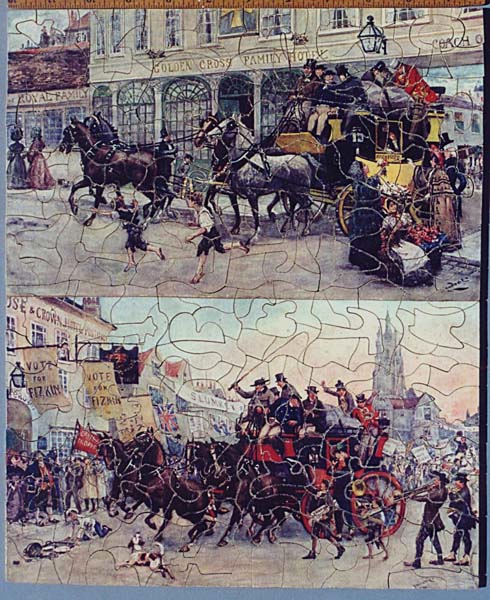

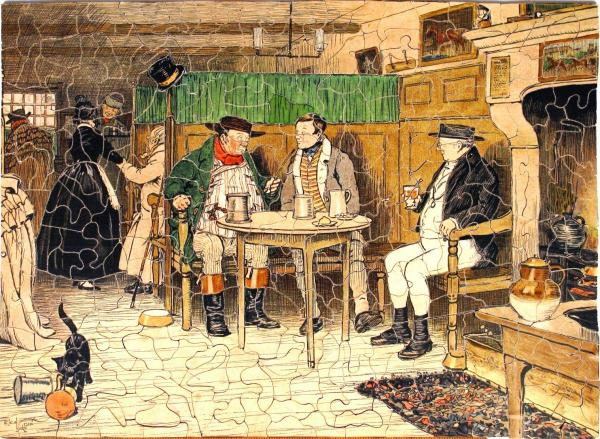

When social settings are represented they promote nostalgia for the past, as in the series of coaching scenes for jigsaw puzzles painted by Ludovici (14 — the following appear courtesy of Bob Armstrong, www.oldpuzzles.com).

The Great War saw the first military use of machines such as tanks and motorized transports whose operators must have enjoyed solving jigsaw puzzles that depicted a pre-industrialised past. As Albert Ludovici, a member of the Royal Academy, wrote in 1926, "I cannot help feeling sorry for the present generation, who have no idea of these good old times, and my only regret is that I did not live in the coaching days, which I have so often tried to depict in my Charles Dickens coaching series of pictures" (qtd. by Armstrong). Ludovici's sixteen paintings were made into jigsaw puzzles by Raphael Tuck in time for the Dickens centennial. Their Englishness is unmistakeable ( 14). Similarly the atmosphere of Cecil Aldin's Sam Weller Meets His Long Lost Parent, a jigsaw from 1912, is suffused with the cozy conviviality of an English inn.

Jigsaws lent themselves to the depiction of complex scenes, but this was not so for postcards and cigarette cards. One effect of abstracting a character from its social environment is to highlight its individual qualities. Pecksniff in this 1919 cigarette card (16) that clearly derives from Phiz's original is the epitome of hypocrisy. Kyd's Cruikshank-based Bumble (17) is the embodiment of pomposity. I would suggest that this reduction to bare essentials sat comfortably within a wartime culture where subtleties are abandoned, simplicities embraced, and cartoons that satirize the enemy flourish. Nick Hiley writes that "the message of Punch's Almanack for 1915 was clear: the war would not be won by fierce emotion, but by the calm assertion of Britishness, and in this the nation's unique sense of humour would play a significant part. Contemporaries firmly believed that the tradition of ridiculing the enemy, not hating him, was quintessentially British" (155). Dickens, together with his original and future illustrators, contributed in no small way to the nation's unique sense of humour and to the quintessentially British tradition of ridicule.

If a wartime culture abandons nuance and embraces simplification this in some way helps to explain the popularity of the stark, unelaborated images of Dickens' characters on cigarette cards and postcards. But their splendid textual isolation was not total since short quotes and descriptions from the novels, such as Heep's umbleness (6), appeared alongside the images or on the reverse of cards (18). In the context of the re-illustration of Dickens' characters at the moment of Englishness and World War I, I find this encapsulation of characters through tag lines, identifying phrases and brief synopses in keeping with the sloganeering prevalent in wartime: "your country needs you"; "do your bit"; "keep calm and carry on." Thus, the simplification of Dickensian images and the abstraction of his texts may be seen as analogous to those forms produced and circulated by the state propaganda machine.

It is difficult to imagine a soldier in the Great War without his cigarette or "fag" as it was then known for, as a London Overseas Club pamphlet put it in 1914, "Under War Conditions Smoking is the One Comfort and Solace." Field rations included two ounces of tobacco a week, and this was supplemented by packets of cigarettes sent from home and from the indefatigable Dickens Fellowship which sent "cakes and cigarettes" and "40 packets of cigarettes" along with the usual mittens and mufflers (Dickensian, March 1915, 80). The Weekly Dispatch launched a "Tobacco Fund" which by October had raised £10,000 towards "smokes" for the troops. So widespread was the circulation of cigarette cards that the Admiralty and War Office censored those which depicted "subjects of a naval and military nature" that might convey "information of value to the enemy" (Times, 15 September 1916, 3). (Because of a shortage of materials production of cigarette cards ceased in 1917.) However, since Micawber, Pecksniff and Heep were not deemed "prejudicial to the public safety or the defence of the realm," they were allowed through. Given the ubiquitous smoking culture it is reasonable to assume that some of the packets of fags received by the troops, especially those from the Fellowship, contained cards portraying Dickens' characters.

Smoking is often a shared activity so I want to conclude by emphasizing the "lived experience” of soldiers' communal encounters with Dickens. While reading is seemingly a private experience it actually takes place within specific social circumstances or relationships, and if we extend the notion of reading to include those engagements with Dickens canvassed in this essay, how much more important are those relationships in wartime: the sharing of a fag in a dugout; the showing of postcards from home; the puzzling together over jigsaws in huts; the reading aloud of extracts from David Copperfield in a Flanders farmhouse; listening to Captain Corbett-Smith recite A Christmas Carol in a barn somewhere in France. These are the wartime equivalents of Dickens’ contemporaries crowding around shop windows to glimpse a recent issue of Nicholas Nickleby, or the reading of the latest number to groups under street lamps or in pubs. All these wartime experiences, underwritten by a Dickensian Englishness that prioritized good fellowship, helped create, maintain, and enhance camaraderie and what has been called "the hidden force which uses the weapons of war to the best advantage" (Koch 327), namely the morale of the troops.

Reading Dickens, in the widest sense of reading, raised a soldier's morale, strengthened his sense of Englishness and helped defeat his greatest enemy, sheer boredom. In June 1916 Captain Roberts wrote about a column of motor lorries: "each lorry was named after a Dickens character painted in letters on the front, and nailed to the side was a painting of a character done on a piece of the tin lining of biscuit boxes. I suppose there must have been forty or fifty of them" (Dickensian 144). For Lieutenant Polack, "more than once the tedium of a lengthy march has been relieved for me when this column has passed by us, by speculating as to the designation of the next lorry" (Dickensian, November 1915, 303). "Life in the trenches," wrote another officer, "is very monotonous, and is relieved by some of the soldiers cutting statues of men and animals out of the chalk through which we have to dig, as we are in a great chalk field. I saw a statue of Charles Dickens, and it was a perfect likeness of him" (Dickensian, January 1916, 4). A convoy of Dickens characters heading towards the front overlooked by a chalk statue of their creator: when Lord Kitchener pointed his finger and commanded "your country needs you!" Dickens, by jingo, answered the call to national service.

List of Figures

Fig. 1: Recruitment Poster, 1914.

Fig. 2: Charles Dickens, Player's cigarette card, 1912

Fig. 3: Phiz, Somebody Turns Up (1849), colourised postcard, 1902

Fig. 4: Fred Barnard, Uriah Heep, Household Edition, 1872

Fig. 5: Fred Barnard, Uriah Heep (1885), Cassell's postcard, 1902

Fig. 6: Kyd, Uriah Heep (1889), postcard 1905

Fig. 7: Kyd, Uriah Heep, Player's cigarette card 1912

Fig. 8: Fred Barnard, Mr. Micawber (1885), Cassell's postcard 1902

Fig. 9: Kyd, Mr. Micawber (1889), postcard 1905

Fig. 10: Kyd, Mr. Micawber, Player's cigarette card 1912

Fig. 11: Unknown artist, Micawber, Cope's cigarette card c. 1910

Fig. 12: George Cruikshank, Oliver claimed by his affectionate friends (September 1837)

Fig. 13: Kyd, Bill Sikes (1889), postcard c. 1905

Fig. 14: Albert Ludovici, Coaching scenes, jigsaw 1912

Fig. 15: Cecil Aldin, Sam Weller Meets His Long Lost Parent, jigsaw c. 1912

Fig. 16: Unknown artist, Pecksniff, cigarette card 1919

Fig. 17: Kyd, Bumble (1889), postcard c. 1905

Fig. 18: Reverse of 10 [Player's, 2nd. Series, no. 41]

Works Cited

Barnard, Frederick, and M. Walton.

Barnard, Fred, et al. Scenes and characters from the works of Charles Dickens; being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings, by Fred Barnard, Hablot K. Browne (Phiz); J. Mahoney; Charles Green; A. B. Frost; Gordon Thomson; J. McL. Ralston; H. French; E. G. Dalziel; F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes; printed from the original woodblocks engraved for "The Household Edition". London: Chapman and Hall, 1908.

Brooks, David. The Age of Upheaval: Edwardian Politics, 1899-1914. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1995.

Chesterton, G. K. Charles Dickens. 1906. London: Burns and Oakes, 1975.

Cordery, Gareth. "The Construction of Dickensian Englishness." An Edwardian's View of Dickens and His Illustrators: Harry Furniss's 'A Sketch of Boz.'. Greensboro, NC: ELT Press, 2005. Pp. 16-22. (Review of) Gareth Cordery & Joseph S. Meisel's edition of The Humours of Parliament: Harry Furniss's View of Late-Victorian Culture.

Crotch, Walter W. "The Decline — And After!" The Dickensian 15 (1919). 121-27.

Hiley, Nicholas. "'A New and Vital Moral Factor': Cartoon Book Publishing in Britain During the First World War." Publishing in the First World War: Essays in Book History. Ed Mary Hammond and Shafquat Towheed. Houndsmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. 148-78.

Koch, Theodore Wesley. Books in War: The Romance of Library War Service. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1919.

Kumar, Krishnan. The Making of English National Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003.

Maunder, Andrew. "Dickens Goes to War: David Copperfield at His Majesty's Theatre, 1914." Dickens Studies Annual, vol. 45. New York: AMS Press, 2014. 175-203.

Patten, Robert L. Charles Dickens and His Publishers. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1978.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana UP, 1978.

Vincent, David. Literacy and Popular Culture: England 1750-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 1989.

Waller, Philip. Writers, Readers, and Reputations: Literary Life in Britain, 1870-1918. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006.

Walters, J. Cuming. "Dickens' Influence on National Character." The Dickensian 6 (1910). 319-20.

White, Jerry. "Tapley in the Trenches: Dickens and the Great War." Dickensian 496 (2015). 108-22.

Last modified 28 September 2017