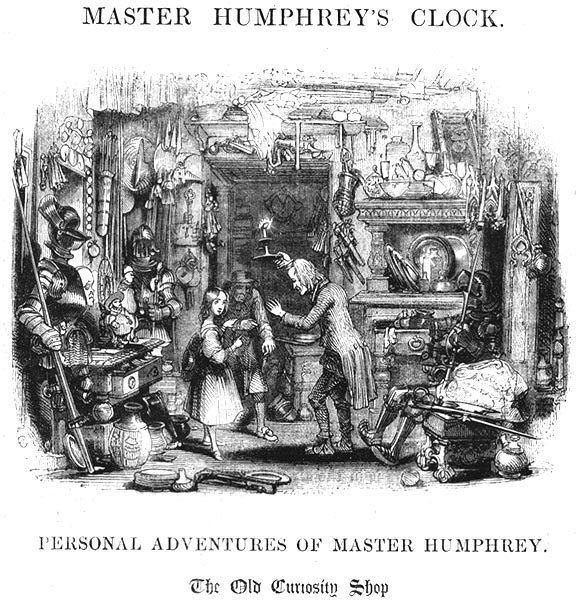

The door being opened, the child addressed the old man as her grandfather, and told him the little story of our companionship (I, 1).] by George Cattermole. Wood engraving, 3 ⅜ x 4 ¼ inches (vignetted image). Chapter 1, first illustration for The Old Curiosity Shop. Original serial publication: 25 April 1840 (first plate in the series) in Master Humphrey's Clock, Part 4. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated

As he turned the key in the lock, he surveyed me with some astonishment which was not diminished when he looked from me to my companion. The door being opened, the child addressed him as grandfather, and told him the little story of our companionship.

"Why, bless thee, child," said the old man, patting her on the head, "how couldst thou miss thy way? What if I had lost thee, Nell!"

"I would have found my way back to you, grandfather," said the child boldly; "never fear."

The old man kissed her, then turning to me and begging me to walk in, I did so. The door was closed and locked. Preceding me with the light, he led me through the place I had already seen from without, into a small sitting-room behind, in which was another door opening into a kind of closet, where I saw a little bed that a fairy might have slept in, it looked so very small and was so prettily arranged. The child took a candle and tripped into this little room, leaving the old man and me together.

"You must be tired, sir," said he as he placed a chair near the fire, "how can I thank you?"

"By taking more care of your grandchild another time, my good friend," I replied.

"More care!" said the old man in a shrill voice, "more care of Nelly! Why, who ever loved a child as I love Nell?" [Chapter I, 6-7]

A Densely Illustrated Weekly Serial (25 April 1840-6 February 1841)

The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-41), which appeared as magazine serial, differs from Dickens's other early novels in the manner and frequency of illustration. Unlike the illustrations in The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club and Nicholas Nickleby, each of its forty weekly instalments was accompanied by one and sometimes two illustrations, but these were not the usual steel-engravings facing pages of text. Rather, Dickens took advantage of the strengths composite woodblock engraving. Although this mode of illustration did not permit the fineness of detail one finds in the monthly-issued engravings for the other early novels, it did permit Dickens to juxtapose text and illustration, thereby creating a highly effective fusion of text and image. As Michael Steig points out, statistics "indicate how this sequential specificity is possible: The Old Curiosity Shop is about five-eighths the length of a novel like David Copperfield, while Barnaby Rudge is about three-fourths the length of such novels; but the Shop has seventy-five illustrations and Rudge seventy-six, compared with the usual forty. Thus proportionately there are two to three times as many illustrations in the weekly installments of Master Humphrey's Clock as in a monthly-parts novel” (52).

According to Jane Rabb Cohen's assessment of Cattermole's contributions to The Old Curiosity Shop, the initial plate is both successful and less than successful in striking the keynotes:

A close study of Cattermole's work for The Old Curiosity Shop, however, makes it apparent that Dickens was moved more by the nostalgic associations evoked by the pictures than by pictures by themselves. Indeed, the artist was more interested in the heroine's picturesque surroundings than in the heroine. Assigned to do the headpiece for Nell's story, as Dickens then regarded it, for example, the artist took special pains in delineating the curiosity shop. Indeed, the interior may have been inspired by his own studio at Clapham Rise with its antique tapestries, armor, and furniture, including a prominent escritoire with carvings of "hideous, gaping, 'Old Curiosity Shop' faces."31 Cattermole took less time with Nell. The author, "more than doubtful of the child's face," which was too old-ladyish, returned it to him for further work. [128]

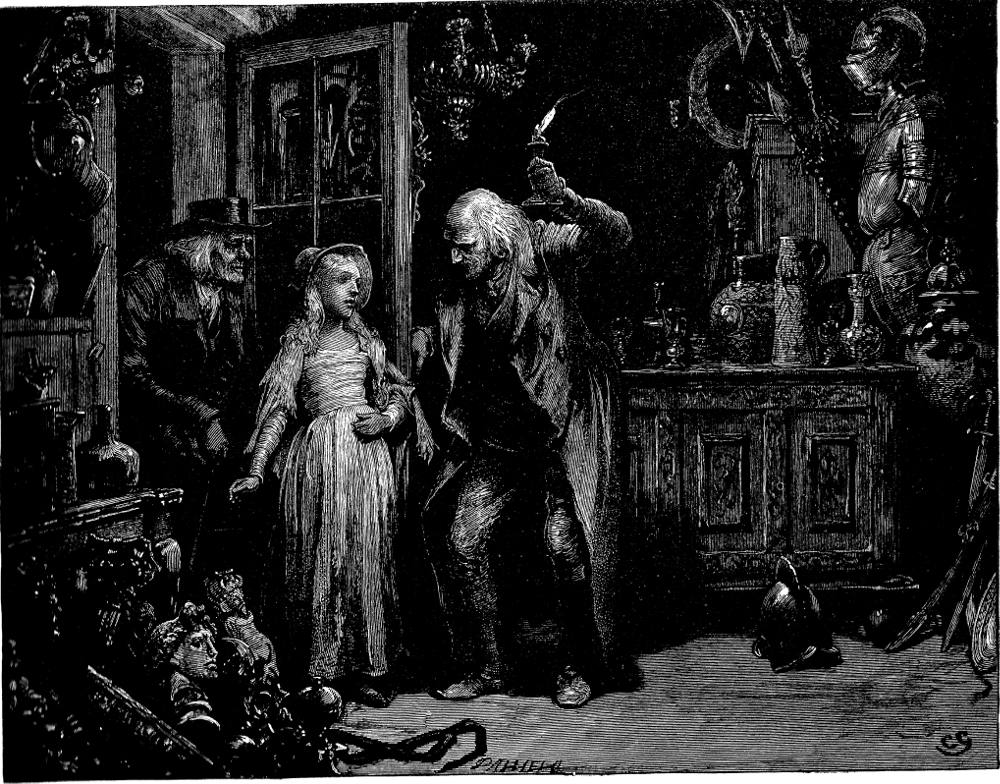

Related Illustrations by Charles Green (1876) and Thomas Worth (1872)

Left: Green has adopted here the style of the dark plate in order to introduce the gloomy interior of Grandfather Trent's place of business which is also his home: The door being opened, the child addressed him as her grandfather (Chapter I). Right: >Worth has clarified the circumstances under which the narrator comes to learn of Little Nell in the first place: "I turned hastily round, and found at my elbows a pretty little girl, who begged to be directed to a certain street" (Chapter I).

Related Material Including Other Illustrated Editions of The Old Curiosity Shop

- The Old Curiosity Shop by Charles Dickens (homepage)

- The Old Curiosity Shop Illustrated: A Team Effort by "The Clock Works."

- The Original Serial Illustrations for The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-41)

- Felix O. C. Darley (4 photogravure plates, 1861)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (12 wood engravings, 1867)

- Thomas Worth (53 wood-engravings, 1872)

- Charles Green (39 wood-engravings, 1876)

- The Old Curiosity Shop by W. H. C. Groome in the Collins' Clear-Type Press Edition (nine lithographs, 1900)

- The Old Curiosity Shop (1910) by Harry Furniss in the British Charles Dickens Library Edition (31 lithographs plus engraved title)

- J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd") (13 lithographs from watercolours)

- Harold Copping (2 chromolithographs selected)

Scanned image and editing by George P. Landow. Caption and Commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "Chapter Five: George Cattermole." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1980. 125-34.

Dickens, Charles. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). London: Chapman and Hall, 1841. Rpt., 1849 by Bradbury and Evans (3 vols. in 2).

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Thomas Worth. Nicholas Nickleby. Illustrated by C. S. Reinhart. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1872. I.

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Charles Green. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. XII.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 3, "From Caricature to Progress: Master Humphrey's Clock and Martin Chuzzlewit." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 51-85.

Stevens, Joan. "'Woodcuts Dropped into the Text': The Illustrations in The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge." Studies in Bibliography. Vol. 20 (1967), 113-34.

Created 7 November 2009

Last modified 14 November 2020